Lucas Simões at Lora Reynolds Gallery, Austin

Glasstire / May 5, 2017 / by Ayden LeRoux / Go to Original

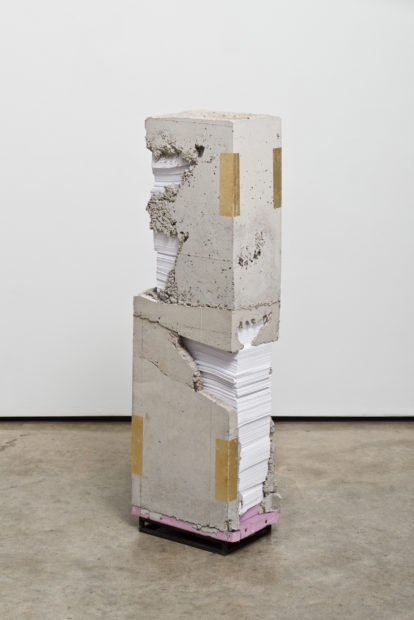

The young Brazilian artist Lucas Simões is nothing if not prolific. His website has more than two dozen projects indexed, most of which are ruminations on the former architect’s two preferred materials: concrete and paper. Trained as an architect, Simões is fascinated with the Brutalist tradition that took hold in the middle of the last century and left a swell of concrete fortresses in international cities. His newest batch of sculptures at Lora Reynolds Gallery in downtown Austin leaves us with his more human and humane idea of Brutalism. They return us to the French term “brut”—the origin of the term Brutalism—meaning raw. Simões’ pillar-like constructions of concrete and paper (with flourishes of brass and gold leaf, used sparingly) abandon the familiar weight of Brutalism for something altogether more gutting.

In the front gallery, a number of pillar-like structures on top of steel frames display stacks of crisp white computer paper entombed within concrete. The paper is wedged and pinched, never bound or held in place by anything except the pressure and weight of the concrete. The crumbling mess of the concrete contrasts with the tidiness of the stacks of paper, which are satisfyingly neat and contained. In one piece, White Lies 4, the paper spills out the side disobediently, fanning down like a waterfall and toppling out of the confines of the rectangular column. Each sculpture seems like a story of encroaching instability versus familiar sturdiness, which feels something like a reflection of this moment in history.

In the back gallery, all but one piece hang on the wall rather than stand on the floor. These sculptures use the same materials but operate in an entirely different language. Here the concrete is smooth and elegant; arching and angular lines create geometric forms. The paper here is a translucent tracing paper (rather than copy paper) and flutters loosely in the ventilation of the gallery. These works are cleaner, and appear kindred to hieroglyphs or totems—two even verge on looking like a holy cross, while the others look like they could hang in the pulpit of a mega-church.

In Terry Tempest Williams’ book When Women Were Birds, Williams’ mother bequeaths her with her collection of journals on her deathbed. As a practicing Mormon, it was traditional for her to keep journals for her entire life. When Williams opens the three shelves of journals at last, she is startled to find that they are empty. In this moment, she sees how little faith her mother had in her religion.

Lucas Simões’ sculptures hinge on something similar. The title of the show and of the pieces, White Lies, is a toothsome metaphor, one that is particularly salient in this era of police brutality and mass incarceration. Inevitably, we confront the fact that as fat as the stacks of paper embedded in concrete are, they are blank. Pages are upheld in spite of communicating nothing. History is protected, sheathed by the legacy of white men, even if the interior could easily be demolished and dismantled once infiltrated. Simões’ interest in the “promises and failures” that buildings offer as functional monuments of each era is apparent in the compact forms in the gallery.

They are the intersection of where his architectural models’ flimsy materials meet the materials of buildings themselves. The immensity and hardness of Brutalist buildings make human bodies within them fragile and diminutive. Yet here Simões’ argument feels hopeful: as much as our bodies might be limited next the scale of hulking complexes of concrete, we can’t forget the power of our hands—they are the instruments that built these structures. We think of concrete as unyielding, but Simões’ work reminds us that the “very nature of power lies in its capacity to be reconfigured and re-signified

In the front gallery, a number of pillar-like structures on top of steel frames display stacks of crisp white computer paper entombed within concrete. The paper is wedged and pinched, never bound or held in place by anything except the pressure and weight of the concrete. The crumbling mess of the concrete contrasts with the tidiness of the stacks of paper, which are satisfyingly neat and contained. In one piece, White Lies 4, the paper spills out the side disobediently, fanning down like a waterfall and toppling out of the confines of the rectangular column. Each sculpture seems like a story of encroaching instability versus familiar sturdiness, which feels something like a reflection of this moment in history.

In the back gallery, all but one piece hang on the wall rather than stand on the floor. These sculptures use the same materials but operate in an entirely different language. Here the concrete is smooth and elegant; arching and angular lines create geometric forms. The paper here is a translucent tracing paper (rather than copy paper) and flutters loosely in the ventilation of the gallery. These works are cleaner, and appear kindred to hieroglyphs or totems—two even verge on looking like a holy cross, while the others look like they could hang in the pulpit of a mega-church.

In Terry Tempest Williams’ book When Women Were Birds, Williams’ mother bequeaths her with her collection of journals on her deathbed. As a practicing Mormon, it was traditional for her to keep journals for her entire life. When Williams opens the three shelves of journals at last, she is startled to find that they are empty. In this moment, she sees how little faith her mother had in her religion.

Lucas Simões’ sculptures hinge on something similar. The title of the show and of the pieces, White Lies, is a toothsome metaphor, one that is particularly salient in this era of police brutality and mass incarceration. Inevitably, we confront the fact that as fat as the stacks of paper embedded in concrete are, they are blank. Pages are upheld in spite of communicating nothing. History is protected, sheathed by the legacy of white men, even if the interior could easily be demolished and dismantled once infiltrated. Simões’ interest in the “promises and failures” that buildings offer as functional monuments of each era is apparent in the compact forms in the gallery.

They are the intersection of where his architectural models’ flimsy materials meet the materials of buildings themselves. The immensity and hardness of Brutalist buildings make human bodies within them fragile and diminutive. Yet here Simões’ argument feels hopeful: as much as our bodies might be limited next the scale of hulking complexes of concrete, we can’t forget the power of our hands—they are the instruments that built these structures. We think of concrete as unyielding, but Simões’ work reminds us that the “very nature of power lies in its capacity to be reconfigured and re-signified