Sun and Earth: Melanie Schiff’s Vivid and Rich Photography

Art Critical / Jul 2, 2014 / by Lindsay Comstock / Go to Original

Melanie Schiff: Run, Falls at Kate Werble Gallery

May 10 to June 20, 2014

83 Vandam Street (at Spring Street)

New York City, 212 352 9700

To place Melanie Schiff in the context of a staid photographic genre would be counterproductive to the poetic space her work inhabits. In her first solo show at Kate Werble Gallery in New York City, “Run, Falls,” she draws us into conversation with the light of Los Angeles — where she has lived since 2008 — and the way it bounces off windows, bends around form and reflects to create layered compositions.

Schiff’s work began as colorful still lifes born of parenthetical youth culture and prosaic inanimate objects: moody mise-en-scène self-portraits with beer bottles in the aftermath of a party scene; half-nude women playing in wild landscapes; references to iconic musicians and albums within images; meditations on light hitting unremarkable objects. She was recognized for it with inclusion in the 2008 Whitney Biennial.

Her current work is a negotiation of the manmade set against the natural environment in a motif that calls for a visceral sense of place in reimagined quotidian scenes. In the aesthetic tradition of photographers like James Welling — whose work is among the canon of post-conceptual Los Angeles artists — Schiff continues to experiment with her medium, elevating the photograph beyond the frozen moment, using multiple or long exposures, unexpected juxtapositions, and as in earlier work, a play with light refraction and reflection. But whereas Welling uses tools like colored gels to alter space and create layers on top of the found environment, Schiff gently intervenes, adding texture with tangible objects (a textile, a window), or using technical processes like motion blur to further manipulate space. Sometimes Schiff doesn’t interfere at all; she allows light to trace its path and reference form. She only gives the viewer the most palpable subject of the image in her titles, freeing the mind to experiment with an underlying narrative syntax that she beckons through movement and enduring heliacal energy.

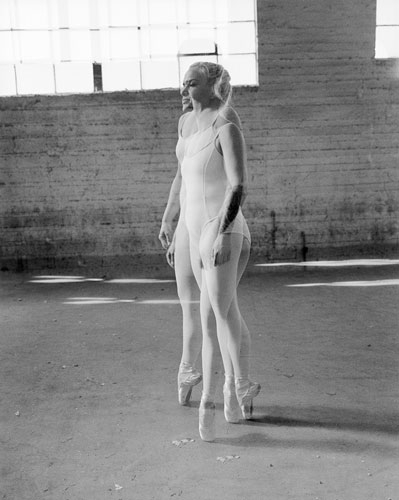

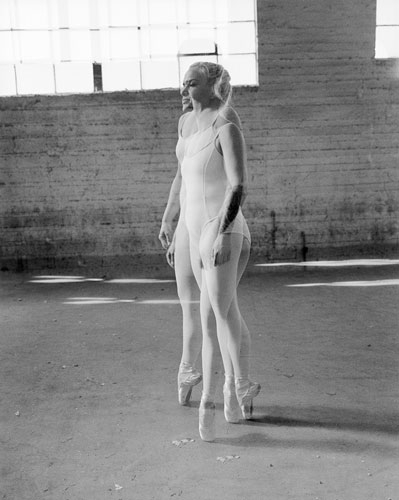

Throughout Schiff’s series, textiles and manmade materials commingle with textures of natural objects. Sometimes waterfalls are overlaid with pattern: a blanket becomes backdrop to weeds, and multiple exposures of a tattooed dancer are an energetic force in an otherwise rigid industrial architectural environment. Those latter pictures, Double Dancer and Dancer and Broom (all 2014) call to mind and provide a contrasting reference to Imogen Cunningham’s portraits of dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham.

On the farthest wall of the gallery, Threadbare I and Threadbare II set the tone for Schiff’s work. The images, which are some of the only color works in the exhibit, are a foray into the artist’s muse: Southern California’s harsh, warm light, which emanates through and peeks around worn oriental rugs. And perhaps by curatorial decision, environmental light is reflected a second time into the images: by light bouncing into the glass frames from the adjacent gallery door. While other reflections abound, smaller framed black-and-white landscapes spaced throughout the exhibit act as reference points, anchoring the series back to earth. T

here are works like Falls, which fits into the genre in a traditional sense, celebrating the watery life-force as portrait, and its counterpart, Triple Falls which is a suggestion of the same waterfall as an abstracted form approaching Cubism. There are less traditional landscapes too, like that of an image of a limb and its darkly clothed body written with light shining through a wicker chair. Where color shows up, it is overshadowed by the sun, which illuminates the composition, turning a monotone world into a spectrum myriad of hues.

A series orchestrated in a roving soliloquy that drifts between genres, Schiff makes work that’s an authentic representation of her social, geographic and solar environment. She plays with

ubiquitous objects and asks us to consider their singular situational relevance, further eschewing boundaries set by formal elements of photography to reframe our expectations of narrative.

In a time when a constant stream of imagery has the power to dilute conscious photographic practice and experimentation with process, Schiff’s work shines. Perhaps she gives us an escape, even if it’s simply in her own reflection; perhaps we just can’t avert our gaze from the sun.

May 10 to June 20, 2014

83 Vandam Street (at Spring Street)

New York City, 212 352 9700

To place Melanie Schiff in the context of a staid photographic genre would be counterproductive to the poetic space her work inhabits. In her first solo show at Kate Werble Gallery in New York City, “Run, Falls,” she draws us into conversation with the light of Los Angeles — where she has lived since 2008 — and the way it bounces off windows, bends around form and reflects to create layered compositions.

Schiff’s work began as colorful still lifes born of parenthetical youth culture and prosaic inanimate objects: moody mise-en-scène self-portraits with beer bottles in the aftermath of a party scene; half-nude women playing in wild landscapes; references to iconic musicians and albums within images; meditations on light hitting unremarkable objects. She was recognized for it with inclusion in the 2008 Whitney Biennial.

Her current work is a negotiation of the manmade set against the natural environment in a motif that calls for a visceral sense of place in reimagined quotidian scenes. In the aesthetic tradition of photographers like James Welling — whose work is among the canon of post-conceptual Los Angeles artists — Schiff continues to experiment with her medium, elevating the photograph beyond the frozen moment, using multiple or long exposures, unexpected juxtapositions, and as in earlier work, a play with light refraction and reflection. But whereas Welling uses tools like colored gels to alter space and create layers on top of the found environment, Schiff gently intervenes, adding texture with tangible objects (a textile, a window), or using technical processes like motion blur to further manipulate space. Sometimes Schiff doesn’t interfere at all; she allows light to trace its path and reference form. She only gives the viewer the most palpable subject of the image in her titles, freeing the mind to experiment with an underlying narrative syntax that she beckons through movement and enduring heliacal energy.

Throughout Schiff’s series, textiles and manmade materials commingle with textures of natural objects. Sometimes waterfalls are overlaid with pattern: a blanket becomes backdrop to weeds, and multiple exposures of a tattooed dancer are an energetic force in an otherwise rigid industrial architectural environment. Those latter pictures, Double Dancer and Dancer and Broom (all 2014) call to mind and provide a contrasting reference to Imogen Cunningham’s portraits of dancer and choreographer Merce Cunningham.

On the farthest wall of the gallery, Threadbare I and Threadbare II set the tone for Schiff’s work. The images, which are some of the only color works in the exhibit, are a foray into the artist’s muse: Southern California’s harsh, warm light, which emanates through and peeks around worn oriental rugs. And perhaps by curatorial decision, environmental light is reflected a second time into the images: by light bouncing into the glass frames from the adjacent gallery door. While other reflections abound, smaller framed black-and-white landscapes spaced throughout the exhibit act as reference points, anchoring the series back to earth. T

here are works like Falls, which fits into the genre in a traditional sense, celebrating the watery life-force as portrait, and its counterpart, Triple Falls which is a suggestion of the same waterfall as an abstracted form approaching Cubism. There are less traditional landscapes too, like that of an image of a limb and its darkly clothed body written with light shining through a wicker chair. Where color shows up, it is overshadowed by the sun, which illuminates the composition, turning a monotone world into a spectrum myriad of hues.

A series orchestrated in a roving soliloquy that drifts between genres, Schiff makes work that’s an authentic representation of her social, geographic and solar environment. She plays with

ubiquitous objects and asks us to consider their singular situational relevance, further eschewing boundaries set by formal elements of photography to reframe our expectations of narrative.

In a time when a constant stream of imagery has the power to dilute conscious photographic practice and experimentation with process, Schiff’s work shines. Perhaps she gives us an escape, even if it’s simply in her own reflection; perhaps we just can’t avert our gaze from the sun.