Photography Sees the Surface @Higher Pictures

Collector Daily / Jul 21, 2015 / by Loring Knoblauch / Go to Original

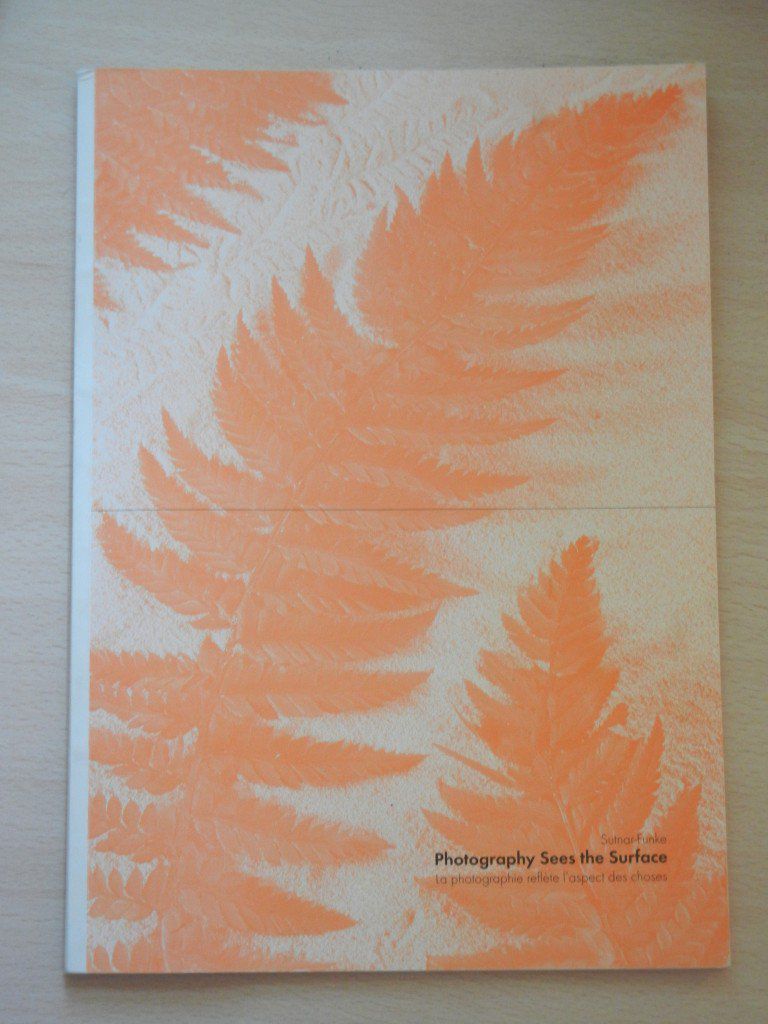

JTF (just the facts): A group show containing the work of 30 different photographers/artists, variously framed and matted, and hung against white walls in the single room gallery space. The show was curated by Aspen Mays, and draws its title from a book published by Jaromir Funke and Ladislav Sutnar in 1935.

Comments/Context: In 1935, the Czech photographer Jaromir Funke, along with his graphic design partner Ladislav Sutnar, embarked on what was intended to be an eight volume set of photographic teaching volumes, integrating images illustrative of the crisp ‘New Vision’ of the times with detailed technical approaches and techniques appropriate for instruction.

The first book in the never-completed series was entitled Photography Sees the Surface, and moves in close to subjects like crumpled textiles, cross sections of wood, human skin, plant forms, crackled Bohemian glass, and sparkling windswept water, discussing the nature of photographic seeing and explaining how to tackle the challenges posed by different kinds of subjects. It is both boldly aspirational about the adventurous power of objectivity and grindingly knee-deep in the how-to of filters, focal lengths, and lighting bulbs.

If Funke had been alive to see the recent images beamed back from Pluto, he would have been happy to see that the surface is still freshly relevant to what photography is and can be. But if he were to circle the walls of this group show, he would find that the definition of ‘surface’ has become exponentially more complex in the intervening years since his thin treatise was published – we’ve moved far beyond the rigors of Modernism, the Bauhaus, and the other objective visual realities he so passionately believed in. In our age, the ways photography interrogates the ‘surface’ have become increasingly nuanced, conceptual, and contradictory, allowing for disparate approaches to using a camera to engage with the world. In a certain way, his highly structured visual ideas provide a convenient contextual jumping off point for the smartly messy multiplicity of what is on view here.

While Funke and Sutnar’s book celebrates the specificity of surface (regardless of the skewed camera angles or clever abstract cropping that may have been employed), the works here probe the uncertainty of surface, and its propensity to confuse and deceive rather than to clarify. The portraits and human forms on view are varyingly obscured. Ellen Carey multiplies her own face into a kaleidoscope of fractured fragments. Jackie Furtado and Eileen Mueller block their subjects’ faces with shadows and hands, while Whitney Hubbs’ self-portrait falls below the surface of the water. Sonja Thomsen peels away the bodies in her image, literally lifting the emulsion off and leaving behind white ghosts, while Ann Hamilton goes outside in, making her mouth a pinhole camera and using the closing of her lips as the shutter.

A second group of works investigates surface as a series of malleable layers and abstractions. Minor White and Frederick Sommer explore the refractions of light using ice on window glass and paint on cellophane respectively as their intermediaries. Justin James Reed and John Opera try to document the surface of nothing, or more specifically the surface of a hole, as seen in the gaping blackness of a cinder block foundation or the feathery raggedness of torn window blinds; Melanie Schiff goes for the corollary, using the light peeking through holes in fabric to interrogate (and animate) its texture. Molly Brandt and AnnieLaurie Erickson take the idea of surface one meta-step further, to the echoes of remembrance found in grave rubbings and afterimage haze, the distortions of these secondary memories still steeped in the fluid essence of their primary subjects.

Many of the other works on view turn back toward Funke and re-embrace the formal qualities of surface.

The white forms of Man Ray’s photogram objects and an anonymous cyanotype of tombstone monuments serve as a reminder of the power of immediacy, providing handy foils for newer efforts. Adam Schreiber turns mundane metal bookends into elegant figure/ground abstractions, while Ben Alper uses the single shadow of a wire to create a perplexingly doubled linear swirl. Pared down form then gives way to more indirect investigations, with Jeff Whetstone, Jessica Mallios and Meghann Riepenhoff attempting to document the very surface of white light itself, turning a flared sunspot, a washed out aerial, and a sinuous darkroom floor photogram into expressions of the ephemeral textures of light. And a handful of space-themed images bend this idea one turn further, where the pinpricks of starlight in the emptiness of the endless dark are the ultimate indefinite ‘surface’.

In a vast wasteland of easy going and largely forgettable summer group shows, this one stands out for its intelligence and thoughtful analysis. Surface has always been central to the idea of photographic seeing, but as this show so deftly points out, the contemporary definitional boundaries of surface have become far more flexible than thinkers like Funke could have ever imagined. In our times, surface can be both categorically precise and intentionally imprecise, and that conflicted, multifaceted duality is what energizes its continued study.

Comments/Context: In 1935, the Czech photographer Jaromir Funke, along with his graphic design partner Ladislav Sutnar, embarked on what was intended to be an eight volume set of photographic teaching volumes, integrating images illustrative of the crisp ‘New Vision’ of the times with detailed technical approaches and techniques appropriate for instruction.

The first book in the never-completed series was entitled Photography Sees the Surface, and moves in close to subjects like crumpled textiles, cross sections of wood, human skin, plant forms, crackled Bohemian glass, and sparkling windswept water, discussing the nature of photographic seeing and explaining how to tackle the challenges posed by different kinds of subjects. It is both boldly aspirational about the adventurous power of objectivity and grindingly knee-deep in the how-to of filters, focal lengths, and lighting bulbs.

If Funke had been alive to see the recent images beamed back from Pluto, he would have been happy to see that the surface is still freshly relevant to what photography is and can be. But if he were to circle the walls of this group show, he would find that the definition of ‘surface’ has become exponentially more complex in the intervening years since his thin treatise was published – we’ve moved far beyond the rigors of Modernism, the Bauhaus, and the other objective visual realities he so passionately believed in. In our age, the ways photography interrogates the ‘surface’ have become increasingly nuanced, conceptual, and contradictory, allowing for disparate approaches to using a camera to engage with the world. In a certain way, his highly structured visual ideas provide a convenient contextual jumping off point for the smartly messy multiplicity of what is on view here.

While Funke and Sutnar’s book celebrates the specificity of surface (regardless of the skewed camera angles or clever abstract cropping that may have been employed), the works here probe the uncertainty of surface, and its propensity to confuse and deceive rather than to clarify. The portraits and human forms on view are varyingly obscured. Ellen Carey multiplies her own face into a kaleidoscope of fractured fragments. Jackie Furtado and Eileen Mueller block their subjects’ faces with shadows and hands, while Whitney Hubbs’ self-portrait falls below the surface of the water. Sonja Thomsen peels away the bodies in her image, literally lifting the emulsion off and leaving behind white ghosts, while Ann Hamilton goes outside in, making her mouth a pinhole camera and using the closing of her lips as the shutter.

A second group of works investigates surface as a series of malleable layers and abstractions. Minor White and Frederick Sommer explore the refractions of light using ice on window glass and paint on cellophane respectively as their intermediaries. Justin James Reed and John Opera try to document the surface of nothing, or more specifically the surface of a hole, as seen in the gaping blackness of a cinder block foundation or the feathery raggedness of torn window blinds; Melanie Schiff goes for the corollary, using the light peeking through holes in fabric to interrogate (and animate) its texture. Molly Brandt and AnnieLaurie Erickson take the idea of surface one meta-step further, to the echoes of remembrance found in grave rubbings and afterimage haze, the distortions of these secondary memories still steeped in the fluid essence of their primary subjects.

Many of the other works on view turn back toward Funke and re-embrace the formal qualities of surface.

The white forms of Man Ray’s photogram objects and an anonymous cyanotype of tombstone monuments serve as a reminder of the power of immediacy, providing handy foils for newer efforts. Adam Schreiber turns mundane metal bookends into elegant figure/ground abstractions, while Ben Alper uses the single shadow of a wire to create a perplexingly doubled linear swirl. Pared down form then gives way to more indirect investigations, with Jeff Whetstone, Jessica Mallios and Meghann Riepenhoff attempting to document the very surface of white light itself, turning a flared sunspot, a washed out aerial, and a sinuous darkroom floor photogram into expressions of the ephemeral textures of light. And a handful of space-themed images bend this idea one turn further, where the pinpricks of starlight in the emptiness of the endless dark are the ultimate indefinite ‘surface’.

In a vast wasteland of easy going and largely forgettable summer group shows, this one stands out for its intelligence and thoughtful analysis. Surface has always been central to the idea of photographic seeing, but as this show so deftly points out, the contemporary definitional boundaries of surface have become far more flexible than thinkers like Funke could have ever imagined. In our times, surface can be both categorically precise and intentionally imprecise, and that conflicted, multifaceted duality is what energizes its continued study.