Meditations in Longing

Hyperallergic / Feb 24, 2014 / by Abe Ahn / Go to Original

LOS ANGELES — The writer Rebecca Solnit once wrote, “Memory, even in the rest of us, is a shifting, fading, partial thing, a net that doesn’t catch all the fish by any means and sometimes catches butterflies that don’t exist.” For artists Golnar Adili and Samira Yamin, the process of remembering is no less imprecise. In their current show at the Craft & Folk Art Museum, the artists demonstrate how memory, even with mnemonic objects like photographs and letters, is mutable and fraught. Only with vigilant effort can remembrance channel the corporeal past.

Adili and Yamin are both Iranian Americans with family histories affected by political upheaval, cultural revolution, and immigration, the latter having lived part of her life in Iran during the period following 1979. The geopolitical events of Iranian history is in the foreground of much of their work, as are the resultant loss and longing. Archival footage in the form of photographs and mementos belie the difficulty of accessing the emotion of their families’ lived experience.

“Scotoma” (2014) is a series of lightbox sculptures and a video installation demonstrating the phenomena of visual auras which precede migraines. Scotomas are caused by nerve disturbances in the brain and appear as spots of light that gradually expand into geometric forms. The video projection begins with a black and white photograph of Yamin’s grandparents, standing at a distance from a crowd of people gathered at what looks to be an outdoor event. A small boy, who could be a nephew or son, walks toward the camera, catty-corner from the couple. It is likely summertime, given the boy’s shorts and the sunglasses being held by Yamin’s grandmother.

Over time, the image loses its clarity as a kaleidoscopic aura emanates from the grandfather’s figure. What begins as a blemish becomes near blindness as the image becomes fragmented by angular forms. Scotomas, unlike retinal migraines, originate from the brain, the repository for memory. What we can recognize or remember is not limited to what our eyes can see but rather what our minds are able to process.

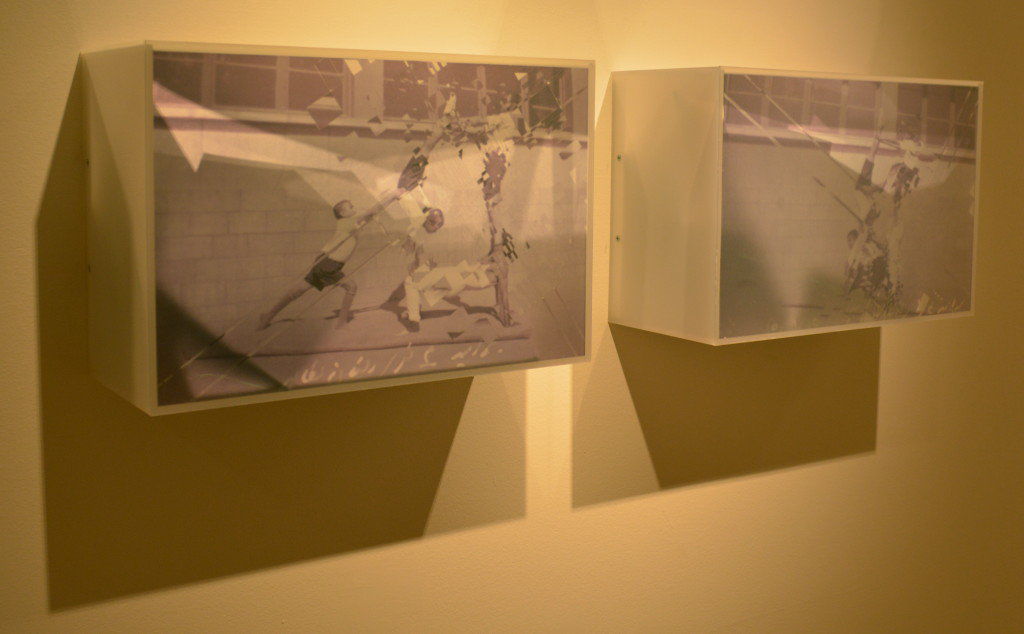

The lightbox photographs in the rest of the series feature nine images of Yamin’s grandfather as a young gymnast. Even when seen from multiple angles, the photographs cannot be perceived as a whole since they have been cut-up to resemble a scotoma. Broken mirrors behind the acrylic panel of the lightboxes diffract light from the museum gallery so as to further mimic a visual aura. What is perceivable are the nebulous frames of young gymnasts, fractured by glints of light, performing acrobatic feats, arms and legs stretched out to extremes, bodies balanced over bodies.

Photographs have the ability to preserve bodily forms. Their human subjects do not age and decay like their biological counterparts. Yamin’s lightboxes perform the unique task of transforming her grandfather’s photographs so they more closely approximate their subjects’ present form, whereupon the living become ghosts of the past. The observer can only surmise their emotional content and fill in the gaps of what we don’t know through conjecture. Photography is but a salve to slow the loss of memory and loved ones. The auras, or scotomas, in Yamin’s images disembody their human subjects as phantoms who live on within the life of a photograph and exist insofar as the living continues to conjure them by remembering.

Deltangi, or “tightness of the heart,” is the leitmotif of Golnar Adili’s latest work, also an effort to recollect the past of a beloved, in this case, her father who died from cancer. An American analog to this is the blues, a sadness and longing for home and lover. The “Gestures” (2013) series features handmade pillows, their plush, inviting surface in contrast with the ghostly imprints of disembodied arms and hands stitched onto their centers. Some of these cut-out images of arms and hands are serially repeated. Others stand alone in pairs. In a display case containing the photographs of Adili’s father are the sources of these disembodied limbs.

The pair of arms in “Standing Pillow I” and “Standing Pillow II” is from a photograph labeled “Father and daughter (1992),” in which the artist’s father is standing next to a young woman who is presumably the artist herself. It is the only photograph in the series in which the father is physically present with his daughter. The disembodied palms in “Patience” come from an image of the artist’s father posing with a group of unidentified men at a concert, while the uplifted arms in “Work Pillow” come from an image of the father installing wallpaper inside a home. The disembodied limbs, and their corresponding titles, bear solemn memories of the father, memories which characterize work, patience, and repose.

Another photograph, sampled by “Embrace,” pictures the father holding a child who is not the artist — a photo dated from his time attending Howard University. Cut out from this context, the father’s arms appear as a strong form of embrace against the plush white pillow. It is the most visceral gesture in the series, but the tender embrace as it is documented in the original photograph is not directed to the artist herself. The photos of Adili’s father suggest an itinerant life resulting in his absence from the artist’s upbringing. Absence, as represented by the disembodied arms and hands in the Gestures series, suggests his absence during life and death.

Hand-stitching the pillows with her father’s gestures is Adili’s performative means of recalling his physical presence. The isolated moments of work, patience, repose, and embrace are not only performed by the father, but the artist herself in the process of needlework. Among the photographs in the father’s archive is an old plane ticket which is repurposed for a large work titled “Perhaps All of the Sky Can’t Turn a Page of This Tightness of the Heart,” a title that is sampled from one of the father’s letters written before his exile from Iran.

The image of a Spantax jet is overlaid with the father’s handwritten script from the letter. The father’s experience of exile and longing are not Adili’s own, but she repurposes the plane ticket and letter to redirect and articulate her own loss and longing. Additional works “Tightness of the Heart I” and “Tightness of the Heart II” reproduce by way of needlework an image of the artist’s bare chest, the latter’s surface intricately mimicking the decorative motifs of traditional Persian glasswork.

In the first work, a plaster model of the Spantax jet protrudes from behind the image of the artist’s chest, framed by the shape of a house. The series culminates in a vulnerable staging of the artist’s displacement, the emotional qualities of which resemble her father’s exile and separation. By bridging her own experience of “deltangi” with her father’s, Adili extends the empathy necessary to produce the emotional intimacy she could not access during her father’s lifetime. Both Yamin and Adili use their family archives to position their loved ones in moments of loss and recovery. The challenge of recovering the past is compounded by physical and historical distance, but both artists are able to glean in fragments the emotional core of memory.