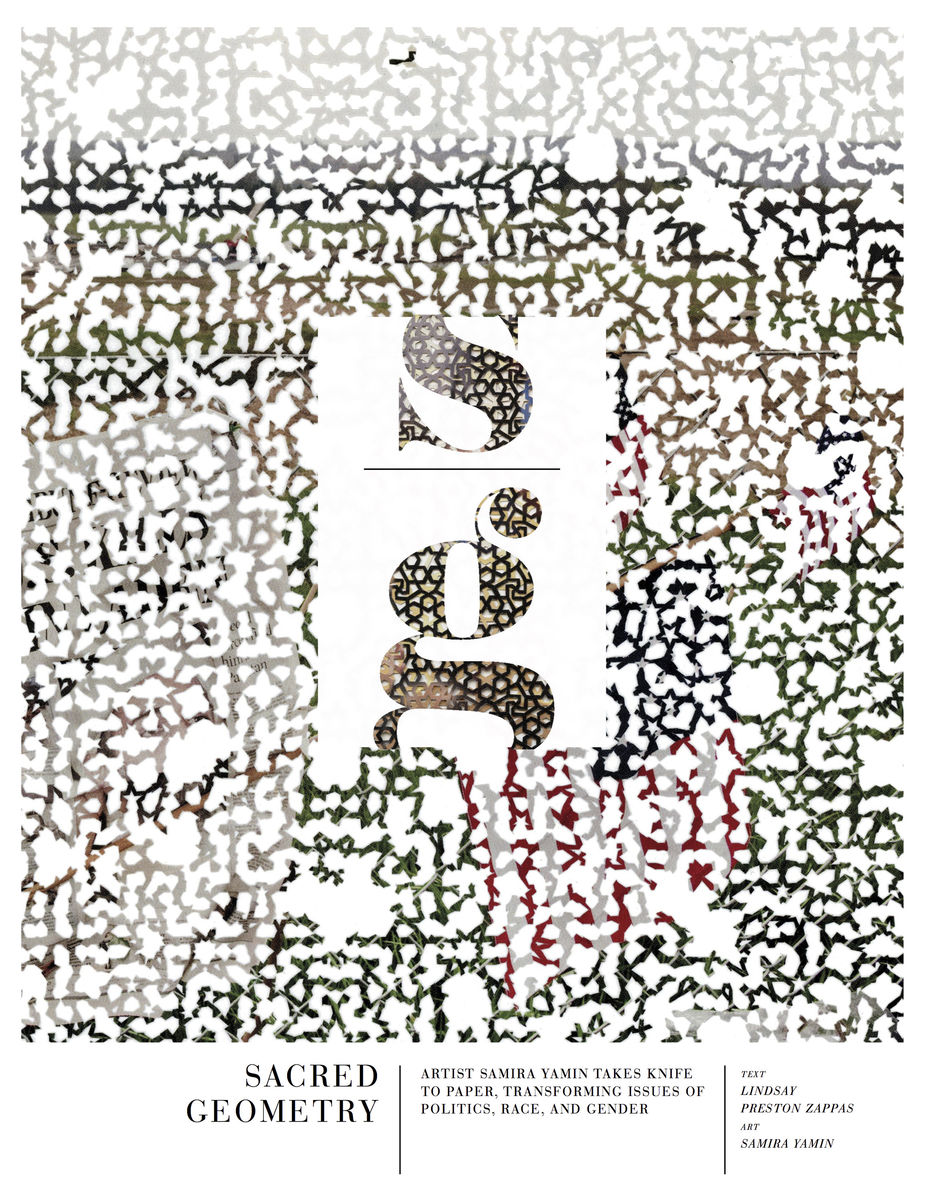

Sacred Geometry

LA Canvas / May 1, 2014 / by Lindsay Preston Zappas / Go to Original

Turns out Samira Yamin and I are neighbors. Like any good neighbor, Samira welcomes me into her Los Angeles studio with a mug of mint tea, and a smile.

Samira’s work is beautiful and delicate, politically charged and heady, yet talking with her in her studio for two hours illuminated themes that run through the work, and the fervor and excitement with which Samira approaches researching new topics of inquiry.

She answers questions with dexterity, promenading through autobiography, and waltzing through subject matter; recalling the skilled and agile movements of her knife through paper. From the orient in western art, to fluid dynamics, to razzle dazzle quilts, Samira has a book and fascinating explanations to accompany each disparate subject matter that enters her brain and becomes imbued in the work. A few times during the interview amidst one of these spirited descriptions, she stops to check herself, “I don’t know how much you like math” (while engaging in a mini science lesson on fluid dynamics), or “Is this interesting to you? Tell me if it’s not interesting.”

Samira’s first semester as an undergrad student at UCLA (where she received degrees in both studio art and sociology) coincided with 9-11, shining a light on a region of the world that Samira felt both culturally and emotionally tied to, and yet having grown up in Los Angeles, distanced from. I applaud any 18-year-old who is brushed up on her world news. At that age, I, perhaps like Samira, was lost in the small realities of a high schooler’s existence—navigating the immense and frightening social terrain.

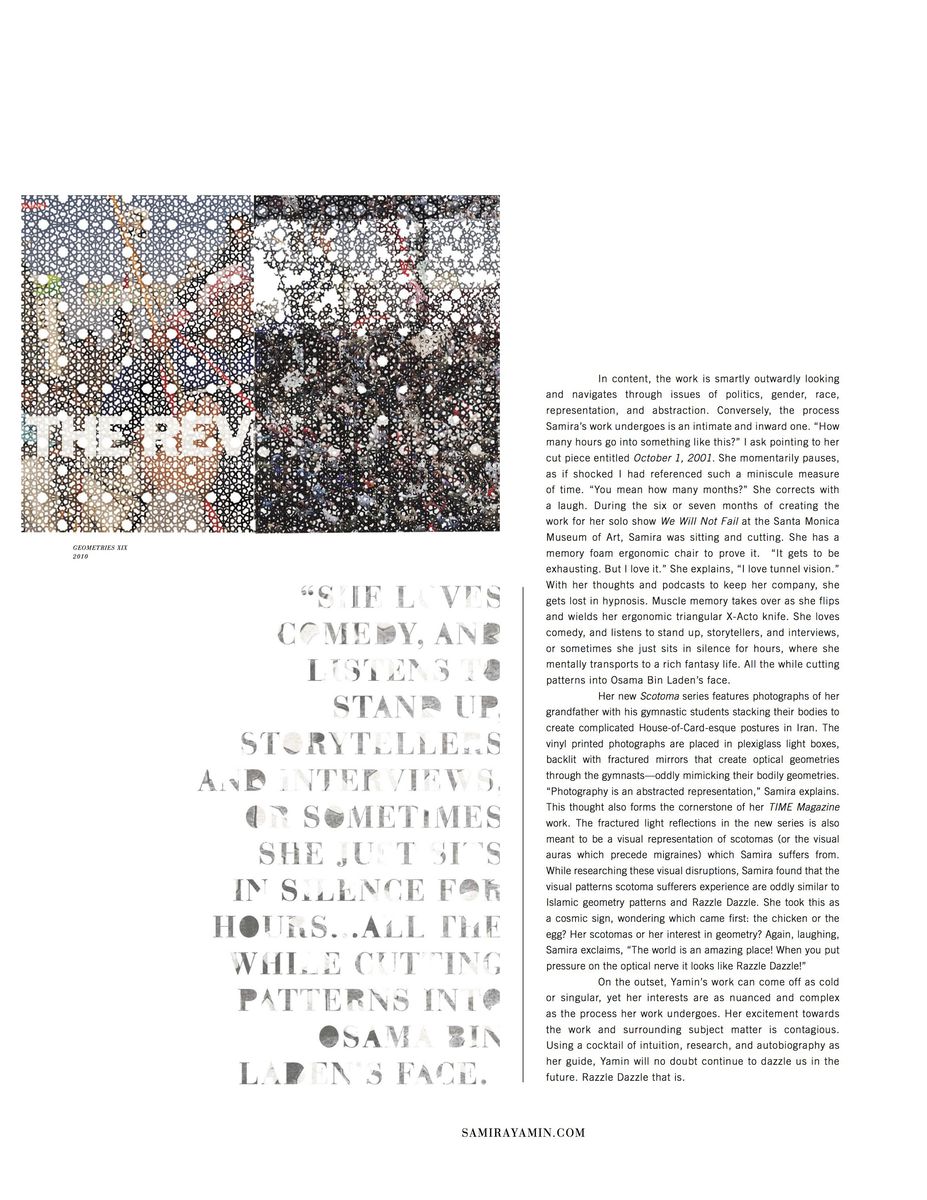

Yet, after 9-11, with a sudden and collective societal focus on the Middle East, Samira began methodically collecting war imagery found in magazines and newspapers as a knee jerk response to dealing with her remoteness from the region. Soon, faced with an evergrowing and haphazard stack of clippings, she began organizing them into broad categories: men, women, then later … dead bodies. This lead her work through phases, yet war photography was always highlighted. Her practice moved from printing war imagery on top of fabrics with Islamic based patterns, to her recent body of work Geometries, in which images from TIME Magazine are beautifully etched by hand, creating a geometric abstraction out of a representational image.

The pieces are layered eye candy: “I really like beautiful things,” she says with a laugh and a twinkle in her eye. “I’m pretty unapologetic about it. I can’t deny it. I like the color gold. I’m Persian, you can blame it on that.” Yet the patterns she deftly fashions over the pages of TIME Magazine are much more complex than just pretty pictures. They are based on Islamic sacred geometries—these gorgeous geometric motifs are meant to diagram the order of the universe and harmonize the physical with the spiritual. Similarly, with one foot on the ground, and one ascending to the clouds, Samira can get lost in touting how amazing the world is if you really look at it, and then in the next breath contradict, or smirk at the cosmic, her strong rationale overpowering the speculative. When talking about the connectedness of the universe, and the patterns that emerge within a TIME Magazine, Samira comments, “It’s really magical that it’s all in there, but at the same time it’s this really dumb object you only see at the dentist’s office.” One foot on the earth. (continued on next page)

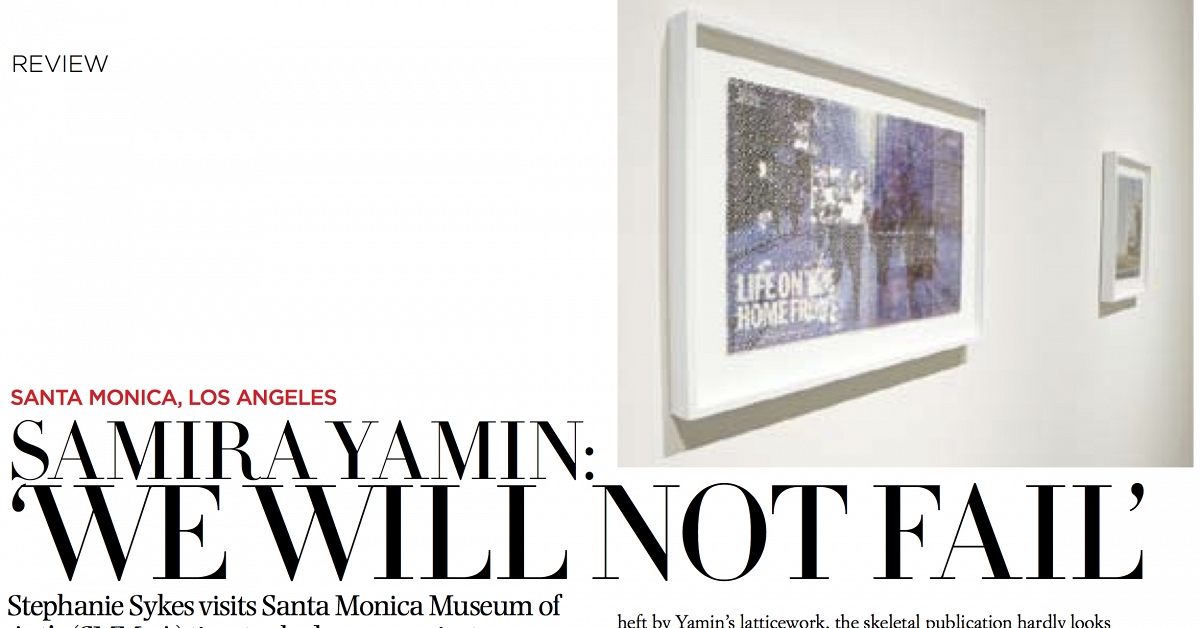

In content, the work is smartly outwardly looking and navigates through issues of politics, gender, race, representation, and abstraction. Conversely, the process Samira’s work undergoes is an intimate and inward one. “How many hours go into something like this?” I ask pointing to her cut piece entitled October 1, 2001. She momentarily pauses, as if shocked I had referenced such a miniscule measure of time. “You mean how many months?” She corrects with a laugh. During the six or seven months of creating the work for her solo show We Will Not Fail at the Santa Monica Museum of Art, Samira was sitting and cutting. She has a memory foam ergonomic chair to prove it. “It gets to be exhausting. But I love it.” She explains, “I love tunnel vision.” With her thoughts and podcasts to keep her company, she gets lost in hypnosis. Muscle memory takes over as she flips and wields her ergonomic triangular X-Acto knife. She loves comedy, and listens to stand up, storytellers, and interviews, or sometimes she just sits in silence for hours, where she mentally transports to a rich fantasy life. All the while cutting patterns into Osama Bin Laden’s face.

Her new Scotoma series features photographs of her grandfather with his gymnastic students stacking their bodies to create complicated House-of-Card-esque postures in Iran. The vinyl printed photographs are placed in plexiglass light boxes, backlit with fractured mirrors that create optical geometries through the gymnasts—oddly mimicking their bodily geometries. “Photography is an abstracted representation,” Samira explains. This thought also forms the cornerstone of her TIME Magazine work. The fractured light reflections in the new series is also meant to be a visual representation of scotomas (or the visual auras which precede migraines) which Samira suffers from. While researching these visual disruptions, Samira found that the visual patterns scotoma sufferers experience are oddly similar to Islamic geometry patterns and Razzle Dazzle. She took this as a cosmic sign, wondering which came first: the chicken or the egg? Her scotomas or her interest in geometry? Again, laughing, Samira exclaims, “The world is an amazing place! When you put pressure on the optical nerve it looks like Razzle Dazzle!”

On the outset, Yamin’s work can come off as cold or singular, yet her interests are as nuanced and complex as the process her work undergoes. Her excitement towards the work and surrounding subject matter is contagious. Using a cocktail of intuition, research, and autobiography as her guide, Yamin will no doubt continue to dazzle us in the future. Razzle Dazzle that is.