In the studio with artist and Spelman College professor Myra Greene

ArtsATL / May 29, 2018 / by Andrew Alexander and Karley Sullivan / Go to Original

Studio images by Karley Sullivan

It’s surprising to arrive in a photographer’s studio to find the artist seated at a sewing machine making a quilt, with no camera, photo equipment or darkroom in sight. But that’s exactly how we arrived to find Spelman photography professor Myra Greene in her studio at the Atlanta Contemporary Art Center.

ArtsATL: You moved to Atlanta not too long ago. How long have you been here?

Myra Greene: I officially moved here last July to start teaching at Spelman. I’m starting the photography program there, which is a whole long beautiful story that I’m very excited about. The year before, I was brought to Spelman as a Distinguished Visiting Professor, so I was living on campus going back and forth to Chicago, and then I officially took the job of Associate Professor and came down. I moved into Atlanta Contemporary in October. I teach photography, but as you can see, everything is really textile-y right now.

ArtsATL: When did you start with the textiles?

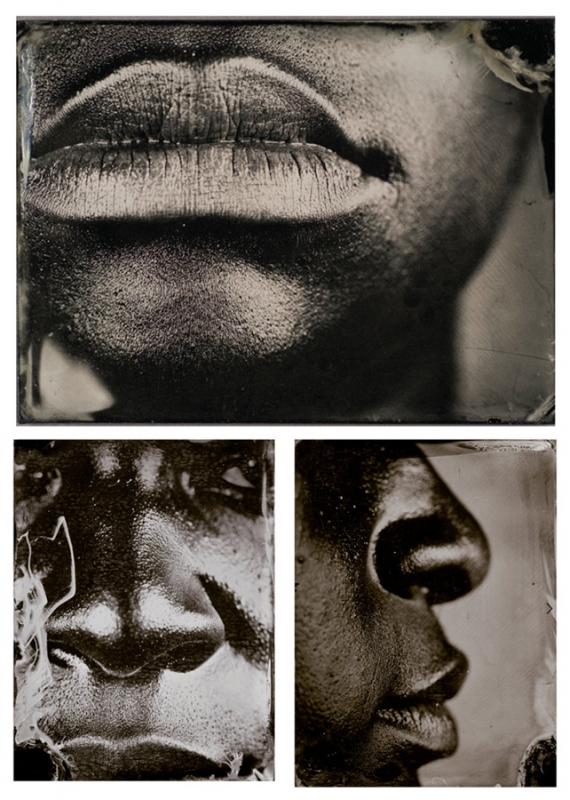

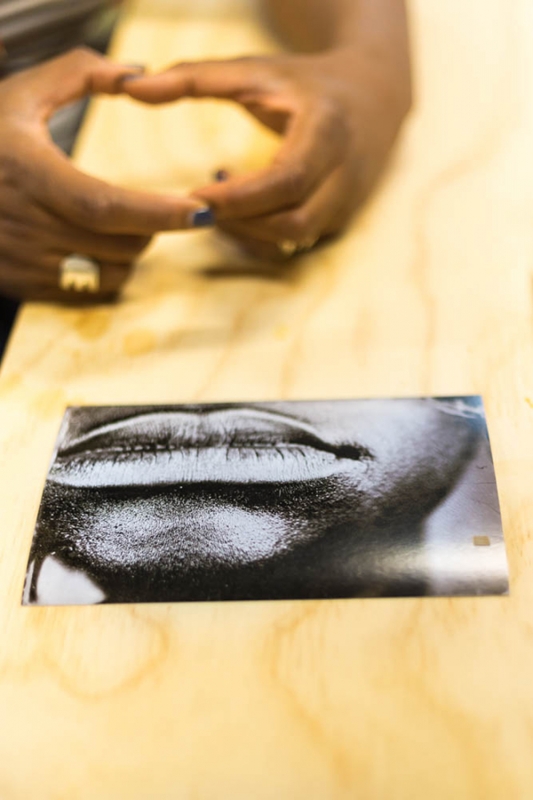

Greene: It started four years ago. I’ll take you through a process. These are black-glass ambrotypes. It’s a 19th century process where the image sits on the surface of glass. I’d been working with my body on a lot of different things. I started to think about: how am I looked at and perceived? That has not really changed since that time period… . Looking is still the same.

ArtsATL: Is this you?

Greene: This is me. It’s a series of seven individual plates I made in 2006–7. They’re one of a kind objects. I’m really interested in photography and its processes and how we think photography is one thing but it’s actually a multiplicity.

ArtsATL: Is the glass inside the camera somehow?

Greene: When you make it, it is. You take a piece of glass, [and] you coat it with collodion. You soak it in silver nitrate to make it light sensitive, and then you put it in the back of the camera to make the exposure. It’s then cured with what is essentially tree sap. There’s ether, so when you buy all the chemicals you get put on a watch list… . These are taken with strobes: there are two strobes nine inches away, [and] the camera is 14 inches away. You just sort of blast your body with light. They’re a very physical thing to make.

ArtsATL: How did you arrive at this process?

Greene: I was living in Rochester at the time. I taught at RIT. There’s a wonderful photography museum, Eastman House, there… . They make a portrait of you. You’re waiting, and then your portrait comes up. I was like, “I look like a slave. Look everyone, I look like a slave!” (I’m a New Yorker, so I just say what I think). A few months later was Katrina. It was the beginning of comments sections, so I would sit and read the comment sections for an hour on a New York Times article. People started saying these really strange things, “Thank god for the deluge” or things about poor black people dying on roofs or looting or their “nature.”

Those two things happened, and I realized it was about looking, it was about images, it was about quick conclusions. How could I chuck that into one project? Then I learned the process.

I kind of got sick of using my own body and the chemistry. I started working with my white friends. I wanted to think about: how does photography apply to whiteness? It’s traumatizing always having this conversation happen on the black body… . I started these in 2007. I was also thinking about the performance of race. We don’t think about that in terms of whiteness, but it truly is a performance if you apply all the ways we talk about racial viewing. It does work with whiteness, it just takes a very long time because it’s very uncomfortable to think about whiteness in those terms… . There are systems of power and privilege that are offered to people and sustained. We casually consume them and spit them back at each other. Photography has been a part of that process for decades. To have someone stop and think about it for a second, hopefully it will have them reconsider the next series of photographs that they consume… . Happily, these were written up in the New York Times. And then I read those comments. I started thinking about: how can I talk about identity politics without using the body? That’s where all the fabric stuff started.

ArtsATL: Did it still come as a surprise to you, the sudden interest in fabric?

Greene: Yes and no. I’d been collecting African fabric for a while. I’d been faux-sewing, meaning I could almost put together an outfit. I started making fabric-collages that then became photographs. I started taking silk-screening classes and embroidery classes. I would buy this African fabric and then resew, thinking about layers, thinking about what is prominent, what is latent, thinking about sexuality, blackness, all the parts of me that are me. How can I think about what sits above and recedes, but only with this abstract language of fabric?

Studio images by Karley Sullivan

I didn’t want to be in the darkroom at that moment. I think about stitches as maps, or locations, where I’ve been, and why I’ve been there. Everything becomes this massive metaphor… . It’s all the things I’m thinking about with photography in terms of frame, elimination, what’s in and out, this conversation about flatness and depth… . There’s a fundamental code that’s buried in a lot of this African fabric. I just asked myself: Is this the base coat of identity? Or of blackness? I don’t necessarily think it is… . The history of African fabric is the most insane thing in the world. European settlers found the fabric. Now they’re the designers. It is then produced in Malaysia and Indonesia and shipped back to Africa and sold as authentic. It’s a coded symbol as to “tradition.” African fabric has its own global diaspora. It doesn’t always relate to blackness or Africanness in any real way, at least in this contemporary moment. You can find African fabrics that have cell phones or pictures of Barack Obama in them… . I started with these small sizes. When my students make something interesting, I always say, “Okay. Make 20 more.” When you’re making 20, things will alleviate and rise and fall and you’ll understand things. Then I started to go up in size. I’m kind of crazy, so I think I’m going to go up in size one more time.

ArtsATL: Do these works have titles. Does the series have a title?

Greene: I gave a talk about this new work, which was called All of the Codes, None of the Codes. That’s what I think these are titled this month.

Studio images by Karley Sullivan

ArtsATL: Do you feel this new phase of work was informed by being in Atlanta, being in the South?

Greene: I don’t know. I’ve lived so many places, I never know how place affects me… . Those small ones I was making when I was living in the dorms at Spelman — I was interested in this, and I didn’t know where it was going to go.

ArtsATL: Are you still taking pictures in Atlanta?

Greene: I just had a show in London [Corvi-Mora] this March. For that I made a new set of ambrotypes on colored stained glass titled Undertones. It was a great show because it was My White Friends on one wall and then the Character Recognition plates on another and then new images from Undertones. Last fall I was making the quilts, stopped and made ambrotypes, [and] then came back to these textiles in the spring.

ArtsATL: You show your work all over. Do you have any interest in showing in Atlanta?

Greene: I do. I haven’t been here long enough to figure out how to do that yet. There’s an interesting contemporary moment here, lots of different practices and processes. I think people are open.

Studio images by Karley Sullivan

ArtsATL: You mentioned you’re from New York, so I imagine you must have grown up around a lot of art and artists. Do you come from a family of artists?

Greene: No. My mother’s fabulous, but not an artist. My sister’s an architect. I went to a predominantly white Catholic high school on the Upper East Side of New York City. I started photography in the seventh grade. We were six blocks away from the Met. That’s what you would do: just go to the Met and look at something. I don’t know when it started happening, but I started going to galleries. The exposure has been really long.

ArtsATL: What were your first pictures of?

Studio images by Karley Sullivan

Greene: Just my friends. There are these twins I knew I’d photograph in the fountains in front of the Met. They were so wacky and weird.

ArtsATL: You’re helping to create Spelman’s photography department. What will the program be like?

Greene: It’s interesting because I’m slowly grasping what it means to start something from scratch and what is necessary and unnecessary. There’s only so much time, [and] there are only so many credit hours people can take. You also have to think about the students who have a very different relationship to photography and images than I did. I grew up knowing what a black-and-white photograph was, making one in a darkroom in undergrad… . It’s completely digital now. What we have then, at a historically all female black college, is an opportunity to really talk about how images function on specific populations. That can correlate into very different explorations. Students aren’t going to make ambrotypes. They still haven’t seen one. But we get to have conversations about privilege or power or communication. The program we’re building is going to be an exposure time. I don’t know how many majors we’ll have, but I hope many students come through the program and have a “touch experience,” where they think about the medium deeply, and then they take that back to their English or their sociology or anthropology degree. It’s a different project than most programs are trying to take on. I’m really excited because hopefully I’ll get a small population of students who I can have really deep conversations with and let them be expansive and monumental in their thinking… . We’ll see. Everyone’s really excited.

This article was made possible by a grant from the Forward Arts Foundation.