10 Emerging Black Male Artists to Collect

Black Art in America / Jun 19, 2018 / by Shantay Robinson / Go to Original

“We polled 10 galleries around the country to provide you with a list of artists currently blazing a trail among fine art collectors” – Najee Dorsey

Black male artists have been recognized by Western art as early as the 19th century with art of landscapes and portraits that was non-denominational. But they have had to overcome great barriers to do that. Robert S. Duncanson was the first internationally known African American painter who found allies in abolitionists. And Edward Mitchell Bannister who earned a bronze medal in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition for his painting Under the Oaks almost lost his prize when the judges found out he was black.

While contemporary culture allows black male artists entrée into traditionally white spaces with content that speaks to the black community, there still isn’t complete equity between those spaces that cater to black art and white art. When representation by black artists is left to the media of the dominant culture, black artists who work with black galleries and are accessible to black fine art collectors, are often overlooked.

Today a number of black male artists are making artworks that contend with contemporary culture’s vices in an effort to highlight the ills of the world. But they are also making beautiful artworks that express humanity in figurative forms placed on canvases and in sculptures. The artists included in this piece include today’s leading emerging black male artists represented by black-owned galleries. Black-owned galleries have promoted the work of black artists for generations and especially during times when black artists were ignored by the white establishment.

Mason Archie is a self-taught artist. But from his mastery of technique, one would think he’s studied with some of the greats. In our postmodern culture, it’s rare to find artists working with realism when so many artists are using their art to make socio-political statements with their work. Archie reverts us back to a simpler time when art was how we captured simple moments, as opposed to our smart phone culture where we capture every moment. His artworks capture the beauty of landscapes that smart phones cannot express.

Jamaal Barber creates prints that tout black pride. While most of his printmaking employs black ink, Barber incorporates pops of color into the technique that offer the viewer some variety. Using figuration and text, the works in his “Black Love Series” and “Current Series” remind black viewers of their resilience. Barber is creating a new kind of propaganda – one that offsets the traditionally negative propaganda about black identity disseminated throughout the United States for generations.

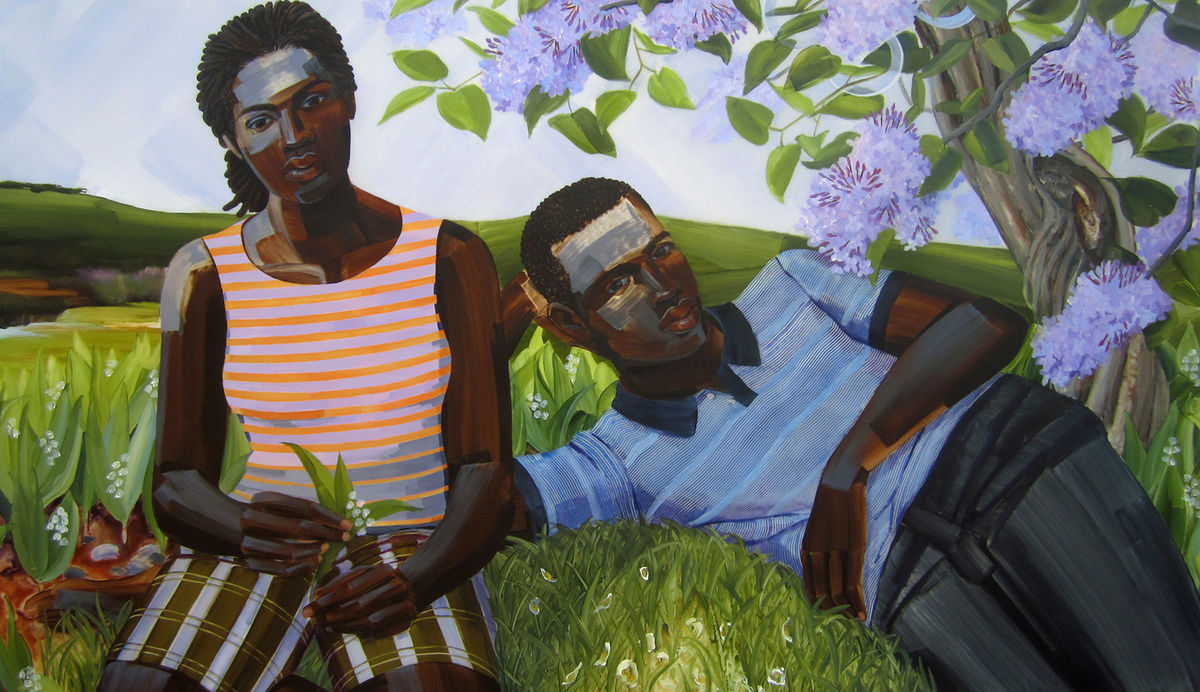

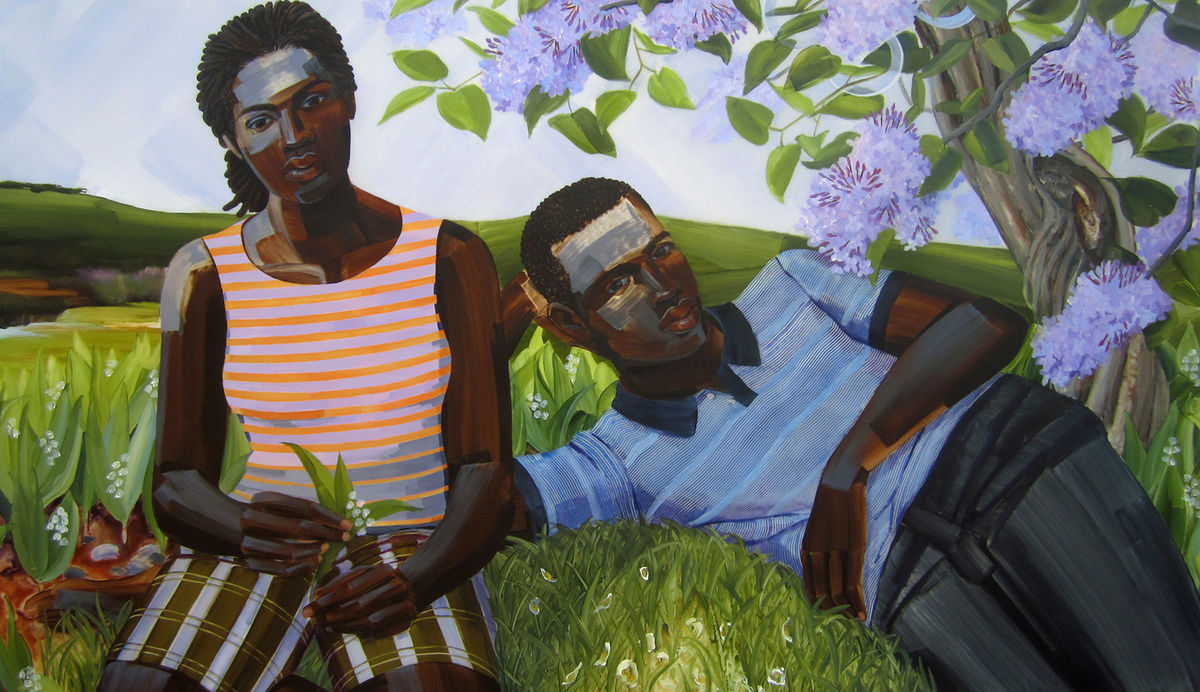

Greg Breda, Resplendent Flame II (First Love, Ish and Isha), 2015.

Greg Breda skillfully uses light and shadows to depict black skin in his latest work. The almost cubist technique gives texture to the facial features and allows for the viewer to experience an almost realistic quality of the subjects he paints of women and men at leisure. Breda’s use of foliage adds to the beauty of the portraits and the textured hair of the subjects adds dimensionality. The subjects do not look directly at the viewer but off to the side as if they were contemplating something more than the leisure they are participating in, relating that even in times of rest, these subjects reflect deeply on the events occurring elsewhere.

Wesley Clark creates assemblages of wood, paint, and other materials to shape narratives about the black male experience in America. The bull’s eyes used throughout Clark’s work beg association with the invisible bull’s eyes on the black man’s back. Artworks like Open Seasonclearly depict the dichotomy between the black civilian male and police officers. My Big Black Americais a masterful assemblage of salvaged wood in the shape of the United States possibly making commentary on the make-up of black America as those who were salvaged from the horrific institution of slavery. The sophistication with which Clark manipulates his materials result in sleek yet rustic pieces that pack encyclopedic meaning into each work. While his color palette is limited, primarily using black paint, the majority of his artworks contain salient meaning and good intention.

Calvin Coleman latest paintings are portraits that are close-ups of the faces of black subjects. They give us intimate looks at the humanity of black people. The textured canvases speak to the emotions conveyed in the countenance of his subject. And they allow the viewer to see not just a body, but the soul. The energy in his brushstrokes offers us movement of the subject as if they were captured by the lens of a camera mid movement. The sincerity of the subjects he’s placed on his canvas begs us to believe in the humanity of people and witness those intimate times that might not be captured in public moments. The bright color palette he uses speaks to the spirit of African American resiliency and fortitude, providing us with hope even at the most difficult times.

Alfred Conteh produces paintings of everyday people. He finds and photographs them on the street and translates their images to the canvas, recreating astoundingly lifelike reproductions of the way the subjects stand, their facial features, and their street clothes. He places the everyday man and woman in spaces where they may never see themselves. But those of us looking at the paintings are forced to see them. Conteh adds dimension to the paintings by adding a layer of what resembles camouflage to the subjects sacrificing the real color of the subjects’ skin and clothing, but really paying careful attention to their facial expression and hair texture. In addition to the portraits Conteh places his subject into scenes of their everyday surroundings in an attempt to add dimension to their narratives.

Epaul Julien repurposes paintings by European masters by photographing subjects that disrupt long-held beliefs about western culture. In Ode to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, he inserts an image of an Asian woman in the place of the original European sitter of the famous painting. In Olympia Met Kat, heinserts a black woman in the reclined nude position with a white servant at her side whereas in the original the main subject is a white woman with her black servant. His “Pop Life Series” features popular American icons including Elvis Presley, Jimmy Hendrix, Angela Davis and Madonna juxtaposed with images that allude to a more complex understanding of these personalities. His use of mixed media, acrylic, and resin create a distressed look, resembling posters exposed to the elements which may lend meaning to the artwork with implications of how these icons have weathered time.

Ervin A. Johnson creates photo-based mixed media made to humanize the black body. In Johnson’s #In Honorseries he creates portraits by photographing his subject in extreme close ups and then distorts the image by dividing the portraits into squares, creating a collage. The effect of the technique used, allows the artists to play with color and shading, which in effect changes the intensity of the portrait by highlighting parts of the subjects’ face or covering up parts such as the eyes or the mouth. Overlaid on the photograph, Johnson uses paint to alter the photographs to intensify the features of the subject.

Walter Lobyn is a DJ, so he recognizes the sacred quality of vinyl records and the ritual of listening to an album. With the scarcity of vinyl records today, Lobyn memorializes them in his art. Using vinyl records to memorialize notable African American figures including Malcom X, Jimi Hendrix, Fela, and Prince, the vinyl is seamlessly incorporated into portraits with the essences of these icons embedded. The melding of the vinyl is masterfully rendered as black skin or hair in some of the pieces and in others the vinyl takes center stage as the subject matter of his artwork.

Kevin Okeith uses an impressionist style to paint images of the human figure and landscapes. Okeith employs techniques reminiscent of modern masters. His use of palette knife allows him to color the flesh of his subjects using minute gestures on the canvas to create rich pigmentation. Okeith’s goal is to promote African beauty by celebrating strength, pride, and dignity. And the simply complex monochromatic landscapes he painted in pink, purple, and black disguise the subject as much as it does highlight it. While using one color, the landscape view Okeith wants the viewer to see is as clear as it is hidden.

Shantay Robinson participated in Burnaway’s Art Writers Mentorship Program, Duke University’s The New New South Editorial Fellowship, and CUE Art Foundation’s Art Critic Mentoring Program. She has written for Burnaway, ArtsATL, ARTS.BLACK, AFROPUNK, Number, Inc. and Washington City Paper. While receiving an MFA in Writing from Savannah College of Art and Design, she served as a docent at the High Museum of Art. She is currently working on a PhD in Writing and Rhetoric at George Mason University.

Black male artists have been recognized by Western art as early as the 19th century with art of landscapes and portraits that was non-denominational. But they have had to overcome great barriers to do that. Robert S. Duncanson was the first internationally known African American painter who found allies in abolitionists. And Edward Mitchell Bannister who earned a bronze medal in the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition for his painting Under the Oaks almost lost his prize when the judges found out he was black.

While contemporary culture allows black male artists entrée into traditionally white spaces with content that speaks to the black community, there still isn’t complete equity between those spaces that cater to black art and white art. When representation by black artists is left to the media of the dominant culture, black artists who work with black galleries and are accessible to black fine art collectors, are often overlooked.

Today a number of black male artists are making artworks that contend with contemporary culture’s vices in an effort to highlight the ills of the world. But they are also making beautiful artworks that express humanity in figurative forms placed on canvases and in sculptures. The artists included in this piece include today’s leading emerging black male artists represented by black-owned galleries. Black-owned galleries have promoted the work of black artists for generations and especially during times when black artists were ignored by the white establishment.

Mason Archie is a self-taught artist. But from his mastery of technique, one would think he’s studied with some of the greats. In our postmodern culture, it’s rare to find artists working with realism when so many artists are using their art to make socio-political statements with their work. Archie reverts us back to a simpler time when art was how we captured simple moments, as opposed to our smart phone culture where we capture every moment. His artworks capture the beauty of landscapes that smart phones cannot express.

Jamaal Barber creates prints that tout black pride. While most of his printmaking employs black ink, Barber incorporates pops of color into the technique that offer the viewer some variety. Using figuration and text, the works in his “Black Love Series” and “Current Series” remind black viewers of their resilience. Barber is creating a new kind of propaganda – one that offsets the traditionally negative propaganda about black identity disseminated throughout the United States for generations.

Greg Breda, Resplendent Flame II (First Love, Ish and Isha), 2015.

Greg Breda skillfully uses light and shadows to depict black skin in his latest work. The almost cubist technique gives texture to the facial features and allows for the viewer to experience an almost realistic quality of the subjects he paints of women and men at leisure. Breda’s use of foliage adds to the beauty of the portraits and the textured hair of the subjects adds dimensionality. The subjects do not look directly at the viewer but off to the side as if they were contemplating something more than the leisure they are participating in, relating that even in times of rest, these subjects reflect deeply on the events occurring elsewhere.

Wesley Clark creates assemblages of wood, paint, and other materials to shape narratives about the black male experience in America. The bull’s eyes used throughout Clark’s work beg association with the invisible bull’s eyes on the black man’s back. Artworks like Open Seasonclearly depict the dichotomy between the black civilian male and police officers. My Big Black Americais a masterful assemblage of salvaged wood in the shape of the United States possibly making commentary on the make-up of black America as those who were salvaged from the horrific institution of slavery. The sophistication with which Clark manipulates his materials result in sleek yet rustic pieces that pack encyclopedic meaning into each work. While his color palette is limited, primarily using black paint, the majority of his artworks contain salient meaning and good intention.

Calvin Coleman latest paintings are portraits that are close-ups of the faces of black subjects. They give us intimate looks at the humanity of black people. The textured canvases speak to the emotions conveyed in the countenance of his subject. And they allow the viewer to see not just a body, but the soul. The energy in his brushstrokes offers us movement of the subject as if they were captured by the lens of a camera mid movement. The sincerity of the subjects he’s placed on his canvas begs us to believe in the humanity of people and witness those intimate times that might not be captured in public moments. The bright color palette he uses speaks to the spirit of African American resiliency and fortitude, providing us with hope even at the most difficult times.

Alfred Conteh produces paintings of everyday people. He finds and photographs them on the street and translates their images to the canvas, recreating astoundingly lifelike reproductions of the way the subjects stand, their facial features, and their street clothes. He places the everyday man and woman in spaces where they may never see themselves. But those of us looking at the paintings are forced to see them. Conteh adds dimension to the paintings by adding a layer of what resembles camouflage to the subjects sacrificing the real color of the subjects’ skin and clothing, but really paying careful attention to their facial expression and hair texture. In addition to the portraits Conteh places his subject into scenes of their everyday surroundings in an attempt to add dimension to their narratives.

Epaul Julien repurposes paintings by European masters by photographing subjects that disrupt long-held beliefs about western culture. In Ode to Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring, he inserts an image of an Asian woman in the place of the original European sitter of the famous painting. In Olympia Met Kat, heinserts a black woman in the reclined nude position with a white servant at her side whereas in the original the main subject is a white woman with her black servant. His “Pop Life Series” features popular American icons including Elvis Presley, Jimmy Hendrix, Angela Davis and Madonna juxtaposed with images that allude to a more complex understanding of these personalities. His use of mixed media, acrylic, and resin create a distressed look, resembling posters exposed to the elements which may lend meaning to the artwork with implications of how these icons have weathered time.

Ervin A. Johnson creates photo-based mixed media made to humanize the black body. In Johnson’s #In Honorseries he creates portraits by photographing his subject in extreme close ups and then distorts the image by dividing the portraits into squares, creating a collage. The effect of the technique used, allows the artists to play with color and shading, which in effect changes the intensity of the portrait by highlighting parts of the subjects’ face or covering up parts such as the eyes or the mouth. Overlaid on the photograph, Johnson uses paint to alter the photographs to intensify the features of the subject.

Walter Lobyn is a DJ, so he recognizes the sacred quality of vinyl records and the ritual of listening to an album. With the scarcity of vinyl records today, Lobyn memorializes them in his art. Using vinyl records to memorialize notable African American figures including Malcom X, Jimi Hendrix, Fela, and Prince, the vinyl is seamlessly incorporated into portraits with the essences of these icons embedded. The melding of the vinyl is masterfully rendered as black skin or hair in some of the pieces and in others the vinyl takes center stage as the subject matter of his artwork.

Kevin Okeith uses an impressionist style to paint images of the human figure and landscapes. Okeith employs techniques reminiscent of modern masters. His use of palette knife allows him to color the flesh of his subjects using minute gestures on the canvas to create rich pigmentation. Okeith’s goal is to promote African beauty by celebrating strength, pride, and dignity. And the simply complex monochromatic landscapes he painted in pink, purple, and black disguise the subject as much as it does highlight it. While using one color, the landscape view Okeith wants the viewer to see is as clear as it is hidden.

Shantay Robinson participated in Burnaway’s Art Writers Mentorship Program, Duke University’s The New New South Editorial Fellowship, and CUE Art Foundation’s Art Critic Mentoring Program. She has written for Burnaway, ArtsATL, ARTS.BLACK, AFROPUNK, Number, Inc. and Washington City Paper. While receiving an MFA in Writing from Savannah College of Art and Design, she served as a docent at the High Museum of Art. She is currently working on a PhD in Writing and Rhetoric at George Mason University.