Kay Hofmann: The Stone Cutter

Glamour GIrl, Issue Six / Apr 10, 2019 / by O. Kristina Pedersen

Forward by MARY ELEANOR WALLACE

Photography by O. KRISTINA PEDERSEN

Written by O. KRISTINA PEDERSEN

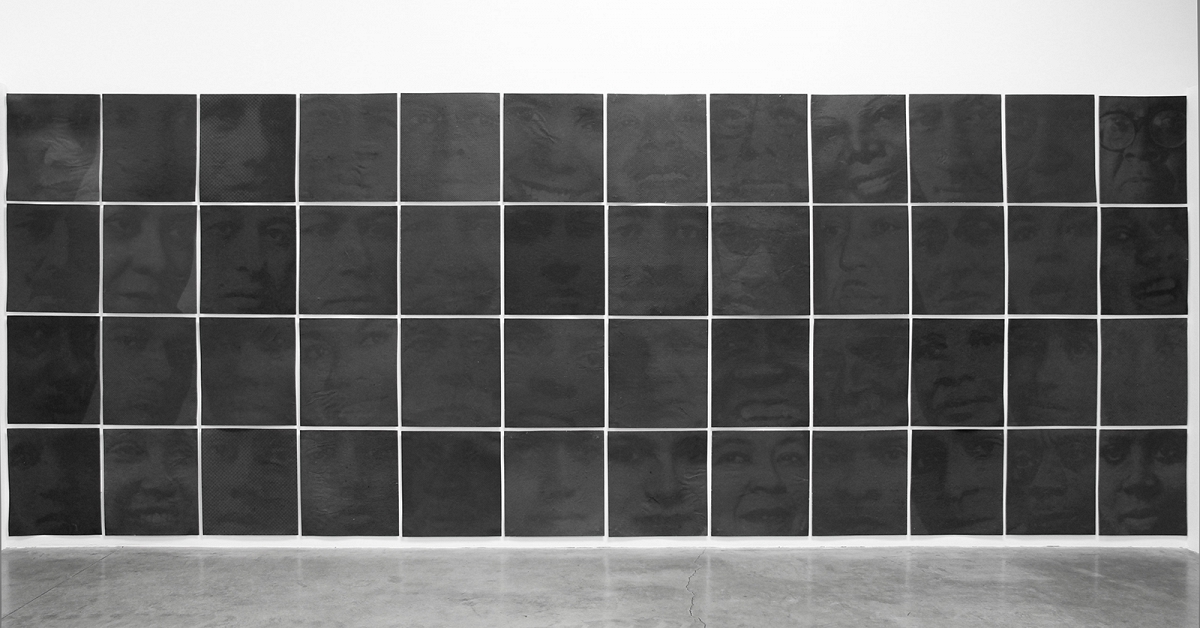

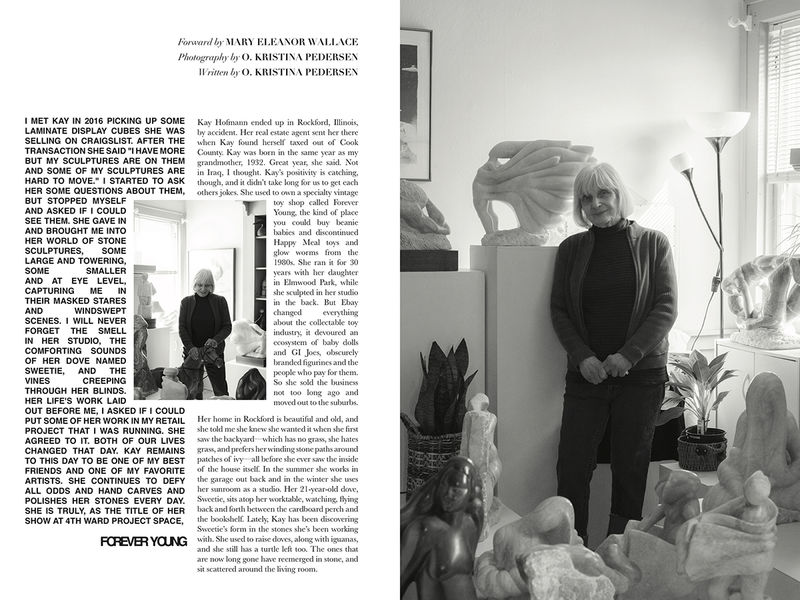

I MET KAY IN 2016 PICKING UP SOME LAMINATE DISPLAY CUBES SHE WAS SELLING ON CRAIGSLIST. AFTER THE TRANSACTION SHE SAID “I HAVE MORE BUT MY SCULPTURES ARE ON THEM AND SOME OF MY SCULPTURES ARE HARD TO MOVE.” I STARTED TO ASK HER SOME QUESTIONS ABOUT THEM, BUT STOPPED MYSELF AND ASKED IF I COULD SEE THEM. SHE GAVE IN AND BROUGHT ME INTO HER WORLD OF STONE SCULPTURES, SOME LARGE AND TOWERING, SOME SMALLER AND AT EYE LEVEL, CAPTURING ME IN THEIR MASKED STARES AND WINDSWEPT SCENES. I WILL NEVER FORGET THE SMELL IN HER STUDIO, THE COMFORTING SOUNDS OF HER DOVE NAMED SWEETIE, AND THE VINES CREEPING THROUGH HER BLINDS. HER LIFE’S WORK LAID OUT BEFORE ME, I ASKED IF I COULD PUT SOME OF HER WORK IN MY RETAIL PROJECT THAT I WAS RUNNING. SHE AGREED TO IT. BOTH OF OUR LIVES CHANGED THAT DAY. KAY REMAINS TO THIS DAY TO BE ONE OF MY BEST FRIENDS AND ONE OF MY FAVORITE ARTISTS. SHE CONTINUES TO DEFY ALL ODDS AND HAND CARVES AND POLISHES HER STONES EVERY DAY. SHE IS TRULY, AS THE TITLE OF HER SHOW AT 4TH WARD PROJECT SPACE, FOREVER YOUNG.

Kay Hofmann ended up in Rockford, Illinois, by accident. Her real estate agent sent her there when Kay found herself taxed out of Cook County. Kay was born in the same year as my grandmother, 1932. Great year, she said. Not in Iraq, I thought. Kay’s positivity is catching, though, and it didn’t take long for us to get each others jokes. She used to own a specialty vintage toy shop called Forever Young, the kind of place you could buy beanie babies and discontinued Happy Meal toys and glow worms from the 1980s. She ran it for 30 years with her daughter in Elmwood Park, while she sculpted in her studio in the back. But Ebay changed everything about the collectable toy industry, it devoured an ecosystem of baby dolls and GI Joes, obscurely branded figurines and the people who pay for them. So she sold the business not too long ago and moved out to the suburbs.

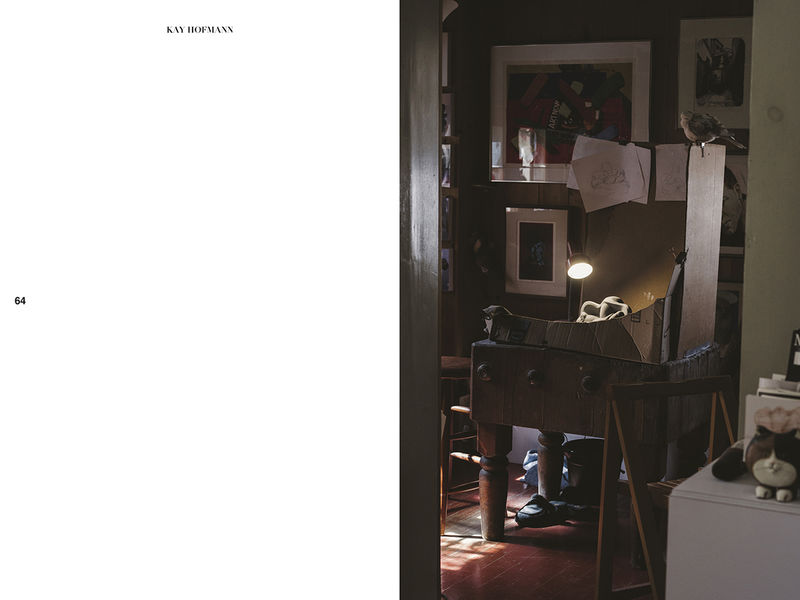

Her home in Rockford is beautiful and old, and she told me she knew she wanted it when she first saw the backyard—which has no grass, she hates grass, and prefers her winding stone paths around patches of ivy—all before she ever saw the inside of the house itself. In the summer she works in the garage out back and in the winter she uses her sunroom as a studio. Her 21-year-old dove, Sweetie, sits atop her worktable, watching, flying back and forth between the cardboard perch and the bookshelf. Lately, Kay has been discovering Sweetie’s form in the stones she’s been working with. She used to raise doves, along with iguanas, and she still has a turtle left too. The ones that are now long gone have reemerged in stone, and sit scattered around the living room.

Kay grew up in Green Bay, Wisconsin. Her father was a stonecutter and made gravestones all his life. She told me that every time they put in a new foundation for a tombstone, they had to take the old marble ones out and replace them— you can’t use marble in cemeteries anymore because it deteriorates so quickly underground. “He had to break these beautiful stones up and it used to kill him,” she said, “so he would bring them back to me, and my first pieces were all made from these old marble tombstones.”

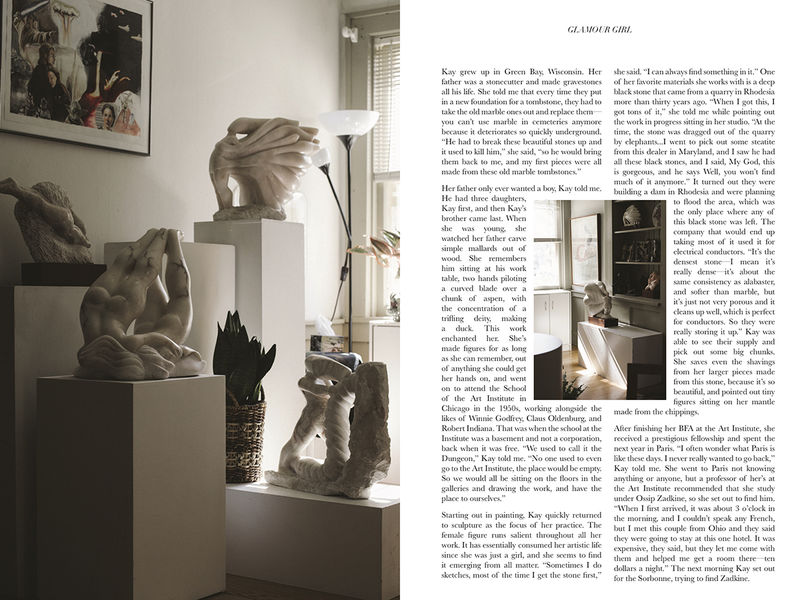

Her father only ever wanted a boy, Kay told me. He had three daughters, Kay first, and then Kay’s brother came last. When she was young, she watched her father carve simple mallards out of wood. She remembers him sitting at his work table, two hands piloting a curved blade over a chunk of aspen, with the concentration of a trifling deity, making a duck. This work enchanted her. She’s made figures for as long as she can remember, out of anything she could get her hands on, and went on to attend the School of the Art Institute in Chicago in the 1950s, working alongside the likes of Winnie Godfrey, Claus Oldenburg, and Robert Indiana. That was when the school at the Institute was a basement and not a corporation, back when it was free. “We used to call it the Dungeon,” Kay told me. “No one used to even go to the Art Institute, the place would be empty. So we would all be sitting on the floors in the galleries and drawing the work, and have the place to ourselves.”

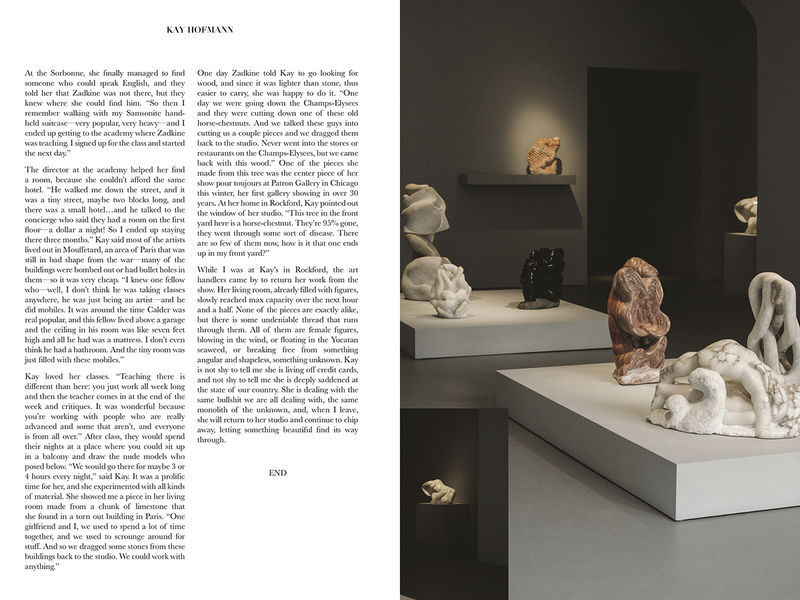

Starting out in painting, Kay quickly returned to sculpture as the focus of her practice. The female figure runs salient throughout all her work. It has essentially consumed her artistic life since she was just a girl, and she seems to find it emerging from all matter. “Sometimes I do sketches, most of the time I get the stone first,” she said. “I can always find something in it.” One of her favorite materials she works with is a deep black stone that came from a quarry in Rhodesia more than thirty years ago. “When I got this, I got tons of it,” she told me while pointing out the work in progress sitting in her studio. “At the time, the stone was dragged out of the quarry by elephants…I went to pick out some steatite from this dealer in Maryland, and I saw he had all these black stones, and I said, My God, this is gorgeous, and he says Well, you won’t find much of it anymore.” It turned out they were building a dam in Rhodesia and were planning to flood the area, which was the only place where any of this black stone was left. The company that would end up taking most of it used it for electrical conductors. “It’s the densest stone—I mean it’s really dense—it’s about the same consistency as alabaster, and softer than marble, but it’s just not very porous and it cleans up well, which is perfect for conductors. So they were really storing it up.” Kay was able to see their supply and pick out some big chunks. She saves even the shavings from her larger pieces made from this stone, because it’s so beautiful, and pointed out tiny figures sitting on her mantle made from the chippings.

After finishing her BFA at the Art Institute, she received a prestigious fellowship and spent the next year in Paris. “I often wonder what Paris is like these days. I never really wanted to go back,” Kay told me. She went to Paris not knowing anything or anyone, but a professor of her’s at the Art Institute recommended that she study under Ossip Zadkine, so she set out to find him. “When I first arrived, it was about 3 o’clock in the morning, and I couldn’t speak any French, but I met this couple from Ohio and they said they were going to stay at this one hotel. It was expensive, they said, but they let me come with them and helped me get a room there—ten dollars a night.” The next morning Kay set out for the Sorbonne, trying to find Zadkine.

At the Sorbonne, she finally managed to find someone who could speak English, and they told her that Zadkine was not there, but they knew where she could find him. “So then I remember walking with my Samsonite hand- held suitcase—very popular, very heavy—and I ended up getting to the academy where Zadkine was teaching. I signed up for the class and started the next day.”

The director at the academy helped her find a room, because she couldn’t afford the same hotel. “He walked me down the street, and it was a tiny street, maybe two blocks long, and there was a small hotel…and he talked to the concierge who said they had a room on the first floor—a dollar a night! So I ended up staying there three months.” Kay said most of the artists lived out in Mouffetard, an area of Paris that was still in bad shape from the war—many of the buildings were bombed out or had bullet holes in them—so it was very cheap. “I knew one fellow who—well, I don’t think he was taking classes anywhere, he was just being an artist—and he did mobiles. It was around the time Calder was real popular, and this fellow lived above a garage and the ceiling in his room was like seven feet high and all he had was a mattress. I don’t even think he had a bathroom. And the tiny room was just filled with these mobiles.”

Kay loved her classes. “Teaching there is different than here: you just work all week long and then the teacher comes in at the end of the week and critiques. It was wonderful because you’re working with people who are really advanced and some that aren’t, and everyone is from all over.” After class, they would spend their nights at a place where you could sit up in a balcony and draw the nude models who posed below. “We would go there for maybe 3 or 4 hours every night,” said Kay. It was a prolific time for her, and she experimented with all kinds of material. She showed me a piece in her living room made from a chunk of limestone that she found in a torn out building in Paris. “One girlfriend and I, we used to spend a lot of time together, and we used to scrounge around for stuff. And so we dragged some stones from these buildings back to the studio. We could work with anything.”

One day Zadkine told Kay to go looking for wood, and since it was lighter than stone, thus easier to carry, she was happy to do it. “One day we were going down the Champs-Elysees and they were cutting down one of these old horse-chestnuts. And we talked these guys into cutting us a couple pieces and we dragged them back to the studio. Never went into the stores or restaurants on the Champs-Elysees, but we came back with this wood.” One of the pieces she made from this tree was the center piece of her show pour toujours at Patron Gallery in Chicago this winter, her first gallery showing in over 30 years. At her home in Rockford, Kay pointed out the window of her studio. “This tree in the front yard here is a horse-chestnut. They’re 95% gone, they went through some sort of disease. There are so few of them now, how is it that one ends up in my front yard?”

While I was at Kay’s in Rockford, the art handlers came by to return her work from the show. Her living room, already filled with figures, slowly reached max capacity over the next hour and a half. None of the pieces are exactly alike, but there is some undeniable thread that runs through them. All of them are female figures, blowing in the wind, or floating in the Yucatan seaweed, or breaking free from something angular and shapeless, something unknown. Kay is not shy to tell me she is living off credit cards, and not shy to tell me she is deeply saddened at the state of our country. She is dealing with the same bullshit we are all dealing with, the same monolith of the unknown, and, when I leave, she will return to her studio and continue to chip away, letting something beautiful find its way through.

END