Alice Tippit

Art in America / Dec 1, 2018 / by by Elizabeth Buhe / Go to Original

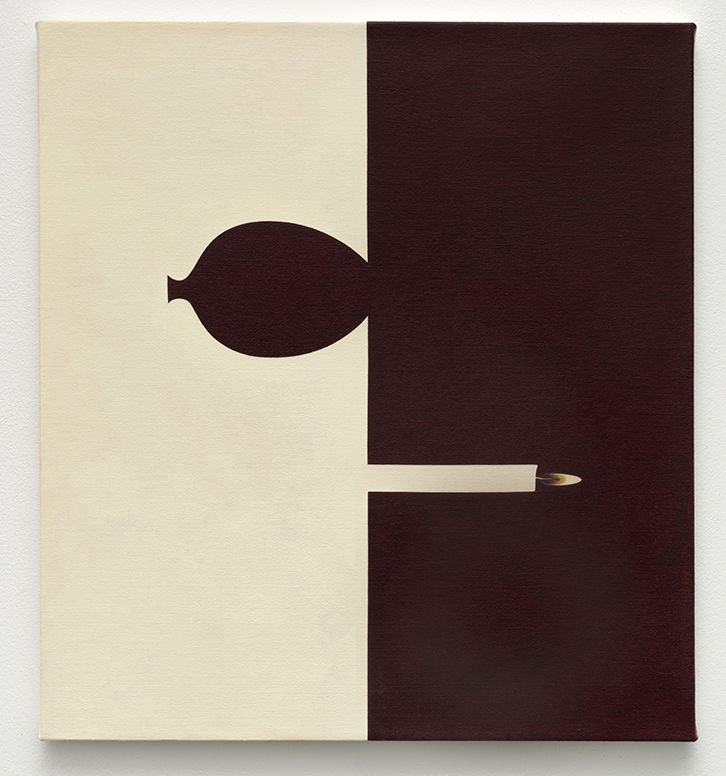

The seventeen bold-hued, hard-edge oil paintings in Alice Tippit’s second solo show at Nicelle Beauchene ricocheted between significations, thwarting any stable meaning. Each painting seemed less a visual manifestation of a single concept or thing than a vessel for a constellation of intertwined ideas. The image in Pop (2017)—comprising two light-brown triangles crowning a peachy, red-tipped orb—conjures inverted ice cream cones, a court jester’s hatted head, and a breast, while the composition of Drape (2017), in which a purple expanse with a scalloped edge is bounded by a billowing pink frame, brings to mind a stage set, window hangings, and a nude figure seen from behind. Unlike more fully abstract works in which countless referents can be “found,” Tippit’s semi-figurative paintings steer viewers toward particular readings, even if multiple ones. More fundamentally, they ask how meaning is made and how forms signify, and where the shifting line is between artist-supplied content and interpretation brought by the viewer.

The forms in the paintings are precisely rendered. Most, whether a svelte flower (Post, 2018) or a ruby red pucker (Born, 2018), exhibit a bilateral symmetry that Tippit achieved by using a paper stencil of half the image, outlining this guide on one side of the canvas in pencil and then flipping it over to draw the opposite half. In other instances, she sketched her form into the wet ground with a brush. That Tippit prefigured the compositions in these ways is evident in the exactitude with which lines meet corners and edges; she crops and lays down the imagery with a care akin to Ellsworth Kelly’s (and with sharp focus: she paints each of her canvases, most of which are between one-and-a-half and two feet per side, in a single day). While the paintings display an overall precision, they are not mechanical-seeming. A cascade of feathery brushstrokes subtly enlivens the pine tree in Spent (2018), for instance, while touches of pale, glowing pink give a pliability to the otherwise flatly rendered flesh in the superb Vise (2017), which depicts a bent arm propped atop a knee.

Like Helen Lundeberg, Robert Indiana, René Magritte, and Tom Wesselmann, Tippit engages themes of desire and spatial confinement through motifs including windows, vases, and monochromatic expanses of bare skin. But her paintings forgo the irony, object fetishism, and surreality that can be found in her predecessors’ work. In place of those qualities is a sincerity, a genuineness with which the artist invites us to join her in the process of making meaning.