Myra Greene: Corvi-Mora

ARTFORUM / May 1, 2020 / by Gilda Williams / Go to Original

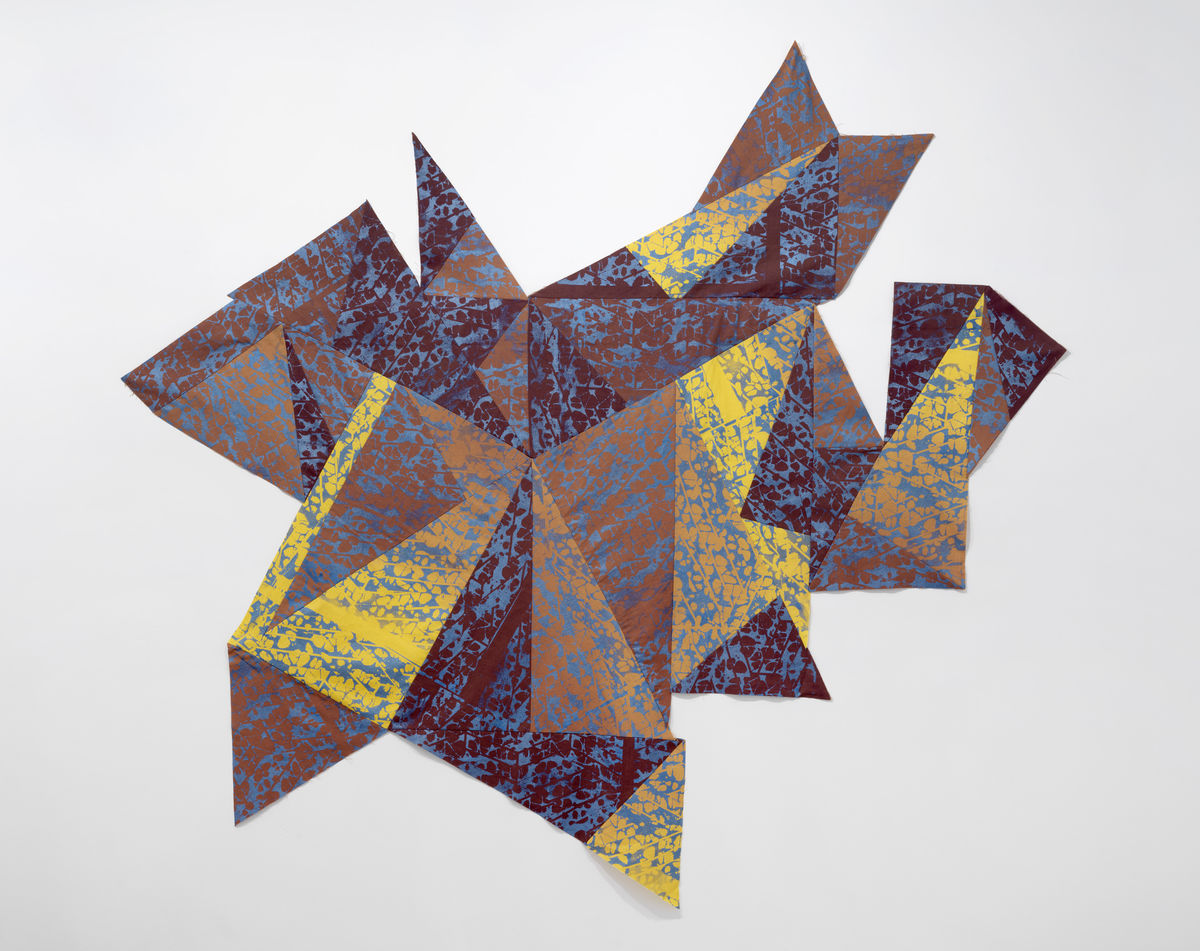

Myra Greene, Piecework #38, 2019, dye and silk-screened ink on cotton, 74 × 68”. From the series “Piecework,” 2017–.

Piecework refers to labor paid according to the number of items produced rather than the amount of time spent on the job. Often associated with the ruthless economic exploitation of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries, this system saw entire families gathered at home sewing garments or packing fruit, united in the desperate attempt to make ends meet. Piecework is sadly making a comeback—thanks to its versatility in allowing employers to get around minimum-wage and other labor laws—as dramatized recently on-screen by a family of Seoul basement dwellers frantically folding pizza boxes to earn measly cash in Bong Joon-ho’s Parasite (2019).

“Piecework,” 2017–, is also the name of an ongoing series of textile pieces by the American artist Myra Greene, consisting of works Greene makes by stitching together variously sized triangular-shaped fabric patches to form thin, quilt-like objects hung directly on the wall. Her recent exhibition “Complementary” included five of them, all dated 2019. Each featured three or four colors in irregular, abstract compositions that expand explosively outward. First, Greene buys colored fabrics and dyes each its complementary shade, often producing layered shades of brown. After the cotton dries, she silk-screens mottled patterns inspired by Dutch wax prints on African textiles—with their complicated colonial history—using metallic inks. Finally, she cuts the dried cotton fabric into triangular pieces of different sizes and sews these into a loosely tessellated pattern. The resulting patchworks expand unpredictably in every direction—not unlike the conversations of the women who once worked together, laboring over quilts. The association between homemade textile works (quilts in particular) and the forging of strong female bonds has long been explored, from the fiction of Margaret Atwood, Toni Morrison, or Alice Walker to the writings of Radka Donnell or bell hooks. Along these lines, Greene, who was born in New York and is based in Atlanta, relates these lovingly stitched, triangulated textile works to the powerful three-way familial ties she shares with her sister and mother.

Greene’s art, which in the past has often centered on photography, addresses labor, color, race, and history. She excels at creating works that allow loaded materials and historically color-coded associations to intersect, that demonstrate the ways in which contingencies shape the perception of color, and that generate new meanings. Her earlier series “Character Recognition,” 2006–2007, borrowed the nineteenth-century technique of ambrotype, an elaborate wet-on-wet photographic process demanding long exposures. Inspired by the “slave daguerreotypes” of the mid-nineteenth century, Greene turned an ethnographic gaze onto herself, creating fragmented close-ups of her own face. The artist also innovated technically, replacing the traditional transparent glass plates with a black background. This process resulted in a spectacular range of silver grays that drew attention to the potentially racialized contours of each disconnected physical feature.

In 2007, Greene shifted attention from her own body toward those of others through a series of “anthropological” photographs. For “My White Friends,” 2007–13, the artist traveled across the United States to photograph friends from various periods of her lifetime—people who shared her past, if not her skin color. Despite vast leaps in media, Greene’s practice is consistently labor-intensive, whether she is engaged in the multistep ambrotype process; the hand dyeing and painstaking sewing of textiles; or the locating of distant friends to be posed and photographed amid conversations around whiteness, belonging, and self-identity. In Greene’s work, artistic effort seems always directed toward bringing together distinct parts that have seemingly broken apart—whether patches of fabric, portions of the black body, distanced family bonds, lost histories, or past friends—to create moments where dispersed fragments can join and cohere into new constellations. In this sense her “Piecework” (peace work?) series is emblematic of her practice overall: perpetually assembling scattered parts in order to look again, more carefully and more closely.