A Projection Into ‘Paths Between Two Steps’ by Soo Shin

Sixty Inches From Center / Apr 11, 2020 / by Amanda Dee / Go to Original

The lymph nodes in my neck are swollen. Poisonous balloons expanding in my throat. I am guilty of my breath, my touch, how they could infect others. I bike to see my partner at Rosehill Cemetery, where we had planned to meet, and I tell him about the wretched mass I sense inside me, surrounding me. So we decide to stay safe, six feet apart, where we will stay for at least a week. We visit his grandparents’ graves, stones placed upon them. He is saying something to me as I draw in and out, in and out wet salty breaths, six feet away. I have never missed a touch so close to me so deeply—I can’t stand it. I go, six feet, then 20, then miles, until I am separated from the one I love. And I am thinking now, as many of us are, what it means to love and to live from a distance.

I am wondering the same thing as I again click through the virtual version of “Paths Between Two Steps,” Soo Shin’s exhibition at Goldfinch Gallery that was indefinitely postponed in March due to social distancing mandates amid the coronavirus pandemic. Or rather, as I wonder this, I can’t stop thinking about “Paths” and the space produced by its gray and black forms and the absence of physical viewers—the resultant void, and what I am projecting into it.

Though when viewing art, I’ve always dealt with separation anxiety. It is a dull pain that sets in right before entering a gallery where I can’t hold onto or interact with the objects that were so carefully thought and formed into being; it can sting like rejection, this denial of the intimacy art had promised us. It’s why I scrawl my own words with abandon across books: to start relationships that will last the turn of the page and to mark where I have been touched by another. Likely, it’s why I write about art, and why I’m writing about it now.

(Seeking: Connection)

“Paths Between Two Steps” at once tells us we will not be given that intimacy, at least not without trepidation. There is not one path, but multiple; it is neither here nor there, but both and nowhere. “Paths Between Two Steps” could be directions shared by a passerby in purgatory or a psychopomp navigating us along dark waterways, where, en route, Place #9 might be a landmark. Place #9 resembles a swing with the soles of lost shoes, calling forth memories of times and places we can no longer access as we once did. Place #9 could also be a doorway, with someone static at the threshold, stuck between times, places, or decisions. Its simple steel frame does not make the position any less stressful to imagine, especially since the proportions of this piece, as in many of Shin’s others, suggest we could fit—or reflect—perfectly into them. It’s almost too easy to step into the shoes she has created.

Like the rest of “Paths,” the sculpture leaves more to be desired in that we are left wanting to fill in blanks, to offer our own memories or feelings, placing the onus of vulnerability on us, though it has to have been transferred from Shin. Shin has described some of her work as “searching for something with my eyes closed,” and I think it must be a kind of bravery, to feel in the dark and create from there, alone.

(Seeking: _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _)

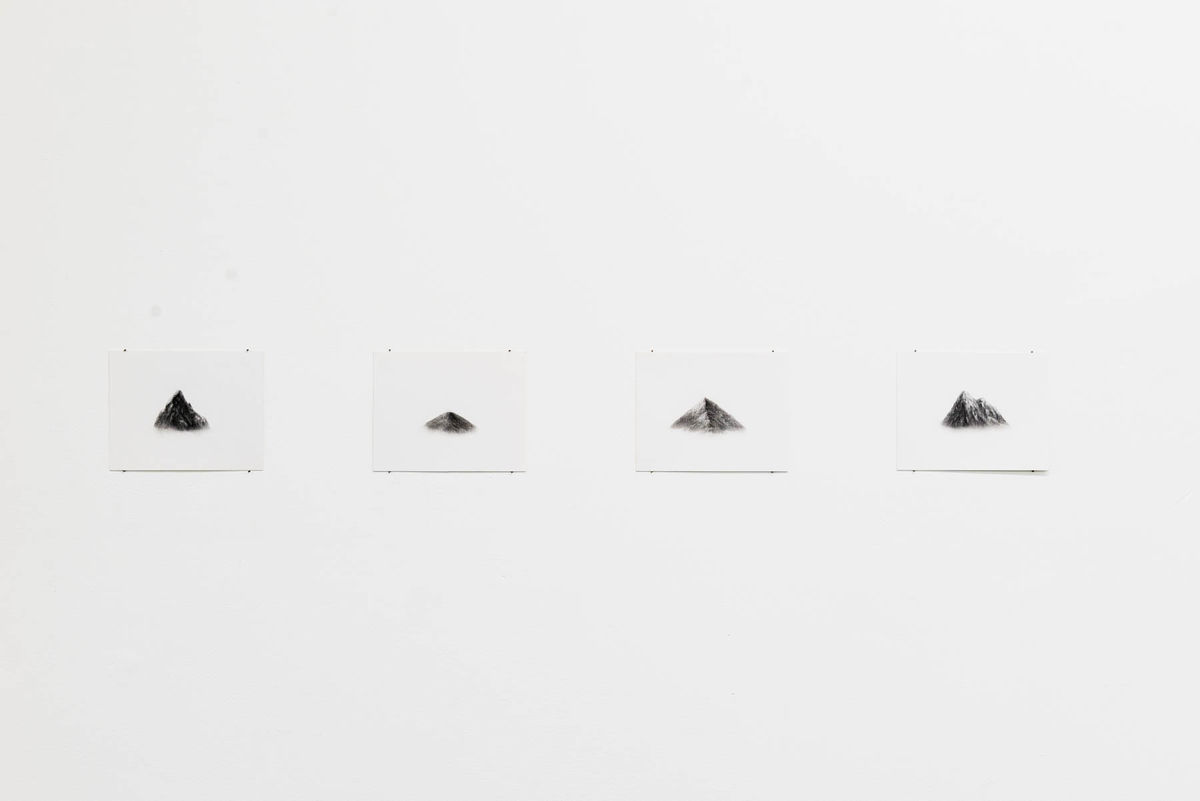

My friend Christie is the first person I know who is hospitalized with what is almost certainly COVID-19 (no tests available). It’s no surprise quarantine is lonely, but she’s the only one I’ve heard talk about how this loneliness reactivates old loneliness. The loneliness is an infection in and of itself. Yet, she says she isn’t thinking about the virus; she’s thinking about the work she has to do now and the mountain of work that will peak once her symptoms fade. Our systems have built these mountains and expect us to move them, no matter what. I’m also thinking about my productivity, this other disease, and how it has made stillness difficult.

I send Christie “Paths,” and she sends back a photo of a 30-feet-tall aluminum man on 47th Street. The metal man sculpture is looking up towards the sun, or something higher. When Christie first moved to Chicago, she would run by the man and think he was looking up towards God. In the Bible, an altar to God is a pile of stones; it is built higher than the ground to get closer when someone offers something of themself. On one bad day, it was gray and rainy and the man looking up into the dripping clouds made Christie cry. Although I never found my faith in the church I was born into, I feel something beyond myself, and both of us, when I see the giant looking up at the sky, through any weather, sent from a friend I love.

Returning to Ground, single footprints on dark vitreous china are assembled in the middle of the room. At first, before, the impressions reassured me as a room full of ghosts would (I enjoy the company but am a little out of my element). Though the empty room of footprints taunts me now. What a gathering this could have been! I long to reach through my screen and make myself known, or see another soul appear.

My friend Tricia responds to Paths over our Zoom call with similar unease, but points to the holes in Invincible Summer (Return to Tipasa). There is a name for this fear, trypophobia, she tells me. To the mind, the holes reek of decay (mortality). Or more simply, the holes remind us of missingness, which is part of what Shin is trying to manifest. She has said that, to her, “searching for the answer or seeking the unknown is often experienced as void.” A call waiting. One summer night, Shin recorded lightning bugs sending out their calls then plotted their light patterns to create the map that is Invincible Summer (Return to Tipasa). Shin cut the panels where the bodies and light had once been. Staring into the holes, I think of the Portuguese word saudade, which has no direct translation in English but roughly means a longing for the past or something that may never have existed—though it still carries hope for the future. Likethe hope of another summer.

Invincible Summer (Return to Tipasa) is a name derived from an essay by Albert Camus (“Return to Tipasa”) in which he writes about the return to a place of his youth that is now marked by ruins of WWII, as well as the quotidian but inescapable markers of time he sees in the older faces he recognizes at cafes that have aged with his own. Although he knows he cannot relive the days of his youth, Camus still re-discovers something invincible within himself by seeking and remembering:

“I recaptured the former beauty, a young sky, and I measured my luck, realizing at last that in the worst years of our madness the memory of that sky had never left me. This was what in the end had kept me from despairing. […] But the memory of that day still uplifts me and helps me to welcome equally what delights and what crushes. In the difficult hour we are living, what else can I desire than to exclude nothing and to learn how to braid with white thread and black thread a single cord stretched to the breaking-point?”

Way before we can reach the breaking point, Shin leaves us in the doorway, alone to pick up each thread and decide what we will do with them. This demands faith, which is why Shin’s work can be intimidating, especially at a time when every step, every morning, can feel like another violation of what we had trusted to be normal. Though as artists, shortly after the high of sharing and connecting to others has dissipated, we return to solitary, alone in the mind, pacing between the corner of potential brilliance and the one crawling with doubts. No one can can walk into that space with you; you must do this part alone.

But hasn’t this always been the process of it all? Although we convince ourselves in our routines and distractions that we are in control, we must begin to braid with shaky hands without knowing how far we can go and where we will end up. True intimacy has never been about certainty or closeness alone but about accepting, not without resistance, the uncertainty and fear of being vulnerable. It’s a lot like faith.

When my throat is no longer swollen, my partner and I return to the cemetery and talk about the stones on the graves. I had read that in Judaism, stones signify permanence. Some believe the stones weigh down interloping souls to tether them to their permanent home. While we lose the ones we love, as the world cracks around us, stones and souls endure. My partner tells me placing stones was just something he did but found comfort in. He didn’t need to know or to believe everything to feel connected to those around him and to something beyond them. I’m trying to sit with this.