The Tension in Liat Yossifor’s Paintings

Hyperallergic / May 29, 2021 / by John Yau / Go to Original

My interest in the paintings of Liat Yossifor is multifold, stemming in part from the way she collapses alla prima painting and figure-ground relationships into something unique. By doing so, she has opened up a distinct space for herself within a domain many thought was no longer possible to work in: drawing in paint on canvas.

In her work, Yossifor rejects the formal claim that drawing in paint (as in Willem de Kooning) evolved into the non-expressionistic use of paint-as-paint (Jackson Pollock). Rather than embracing this view of materiality, she seems to be interested in the connotative possibilities of paint’s materiality when it is explored through alla prima painting and a rethinking of the figure-ground relationship. Her works suggest figural abstractions in which no figure is visible, a preoccupation that was apparent in her early “Portraits” (2005), for which she first gained attention after receiving her MFA from the University of California, Irvine, in 2002.

In an interview with the London-based abstract artist Erin Lawlor, Yossifor, who lives and works in Los Angeles, made this observation about the built-up, impenetrable paintings of the Abstract Expressionist artist Milton Resnick:

“It seems he is seeing something we cannot see. At first, they seem noncommittal; everything is forever in transition and neutral. But they are actually about the state of transition like no other work. They are action paintings without the bravado of “action” and so they offer no relief. All this I admire.”

I was struck by Yossifor’s interest in an action painting sans “bravado,” representing a state of constant transition, and offering no relief. These characteristics all seemed apt to the works in her exhibition Liat Yossifor: Communicating Vessels at Miles McEnery (May 13–June 19, 2021).

Lawlor and Yossifor’s discussion of Resnick and Eugene Leroy, a Flemish painter who adhered to the view that there was a figural presence in his thick, built-up, apparently abstract canvases, also struck me as relevant to Yossifer’s practice.

Yossifor’s paintings are dense with contradictions. They invite viewers to see figural presences that never become pictorially apparent but are sensed throughout her work, in both their texture and the sensuous, linear shapes defined by swirling swaths of paint, the result of what the gallery press release calls “surrealist automatic drawing techniques.”

The exhibition’s title comes from André Breton’s 1932 book Les Vases communicants (The Communicating Vessels), which was partially inspired by Sigmund Freud’s writings about dreams and dreaming, and the connections between the interior imagination and everyday facts. By using this title, Yossifor suggests she believes that paint enables viewers to recognize connections between the imagination and the ordinary world without relying on the overtly pictorial.

The exhibition includes seven human-scale, vertical rectangular works. All the paintings are between 80 and 82 inches tall and vary in width from 60 to 78 inches — measurements that indicate their scale was determined by the artist’s reach. In this sense, we might regard the paintings as portraits of figural actions, rather than of figures.

While viewers are likely to perceive the works as monochromatic, Yossifor has painted each with an undercoating of at least one color. After adding palpable layers of paint, she goes back into the surface with various instruments of different widths. Her process entails building up a painting with an impasto skin and them digging into it, caressing and scratching.

“Portrait I” (2021) reveals traces of blue, brown, white, and a bit of brownish-red in the gouges running through the paint. The gouges and swath of paint are held in check by paths of thick, creamy paint that often run parallel with the painting’s physical edges, serving as a border between what is outside and inside. Within that border, the surface becomes an interlocking, overlapping swirl of paint paths and deep gouges, a controlled series of movements that approach an ecstatic state without ever arriving at frenzied release.

There is a top and bottom to these paintings that is inflected by Yossifor’s acknowledgement that the gestures have to stay within the painting’s physical borders. All of the works contain circular and S-shaped swaths, which evoke a female figural presence that never fully coheres. It is as if the figure is at once emerging from and merging with the paint. This state of transition — of simultaneously appearing and disappearing — does not seem to me purely aesthetic. Rather than resolution, we engage with a state of constant transition without, as Yossifor says, “relief.”

I think Yossifor’s use of industrial grays, black, and dark yellow-ochre as the dominating colors in her work denies any associations with flesh, but it does evoke building materials, such as concrete, onyx, and earth. Her paintings are urban abstractions that tacitly recognize the pressure of anonymity that is integral to the people working in office buildings. The works evoke walls and plastering, as well as the human desire to leave behind one’s permanent mark. The surface shifts — from smooth, creamy pathways to deep gouges — imbue the paintings with an object-like tactility, and render the works topographies sensitive to changing light.

At time when our collective anxieties are pushing for solutions, Yossifor reminds us that answers are likely to be temporary, while change is inescapable. Where that change will lead us cannot be predicted. By working with a wet, viscous material, and making artworks within what is presumably a circumscribed time period, Yossifor becomes a diarist who refuses to tell stories.

Liat Yossifor: Communicating Vessels continues at Miles McEnery Gallery (520 West 21st Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through June 19.

In her work, Yossifor rejects the formal claim that drawing in paint (as in Willem de Kooning) evolved into the non-expressionistic use of paint-as-paint (Jackson Pollock). Rather than embracing this view of materiality, she seems to be interested in the connotative possibilities of paint’s materiality when it is explored through alla prima painting and a rethinking of the figure-ground relationship. Her works suggest figural abstractions in which no figure is visible, a preoccupation that was apparent in her early “Portraits” (2005), for which she first gained attention after receiving her MFA from the University of California, Irvine, in 2002.

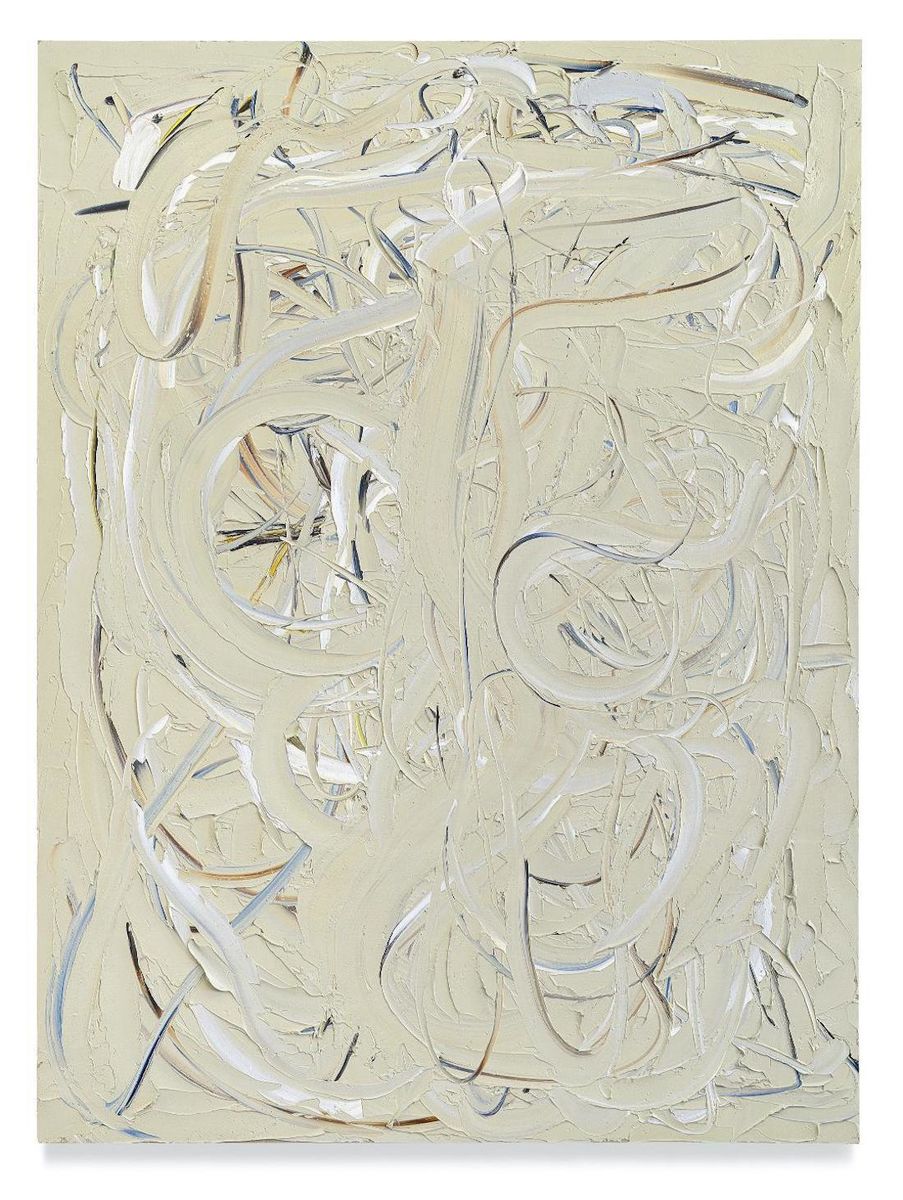

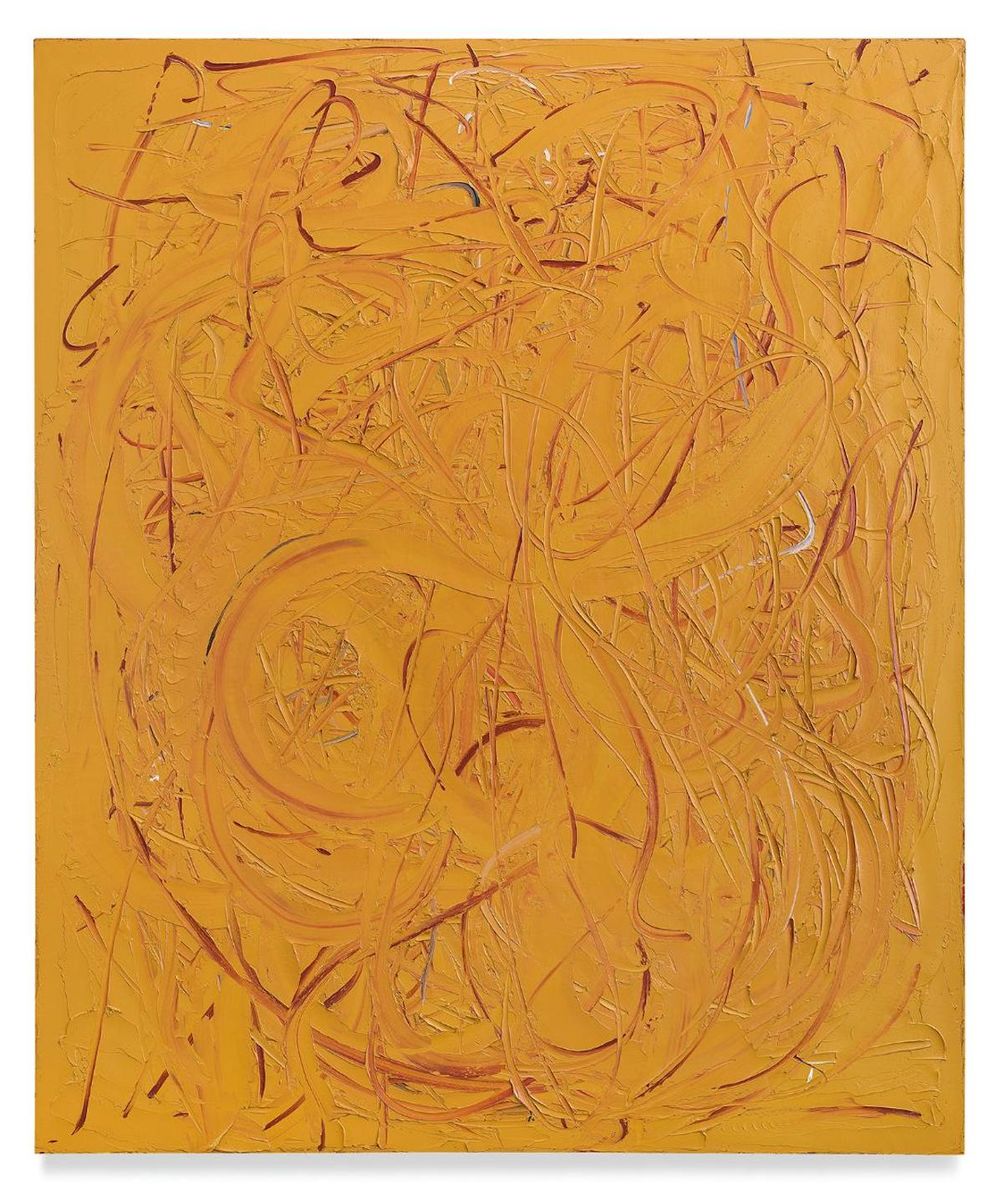

Liat Yossifor, “Water" (2021), oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches

In an interview with the London-based abstract artist Erin Lawlor, Yossifor, who lives and works in Los Angeles, made this observation about the built-up, impenetrable paintings of the Abstract Expressionist artist Milton Resnick:

“It seems he is seeing something we cannot see. At first, they seem noncommittal; everything is forever in transition and neutral. But they are actually about the state of transition like no other work. They are action paintings without the bravado of “action” and so they offer no relief. All this I admire.”

I was struck by Yossifor’s interest in an action painting sans “bravado,” representing a state of constant transition, and offering no relief. These characteristics all seemed apt to the works in her exhibition Liat Yossifor: Communicating Vessels at Miles McEnery (May 13–June 19, 2021).

Lawlor and Yossifor’s discussion of Resnick and Eugene Leroy, a Flemish painter who adhered to the view that there was a figural presence in his thick, built-up, apparently abstract canvases, also struck me as relevant to Yossifer’s practice.

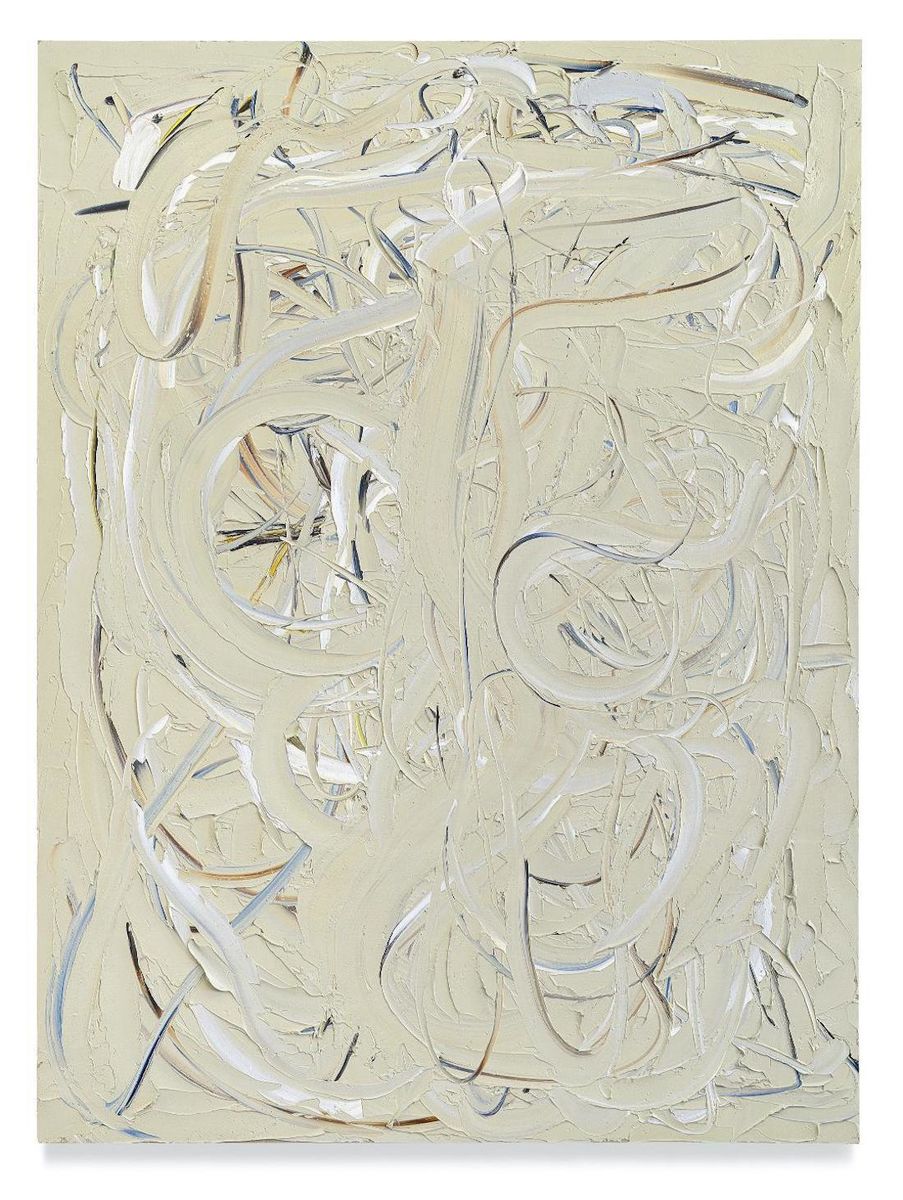

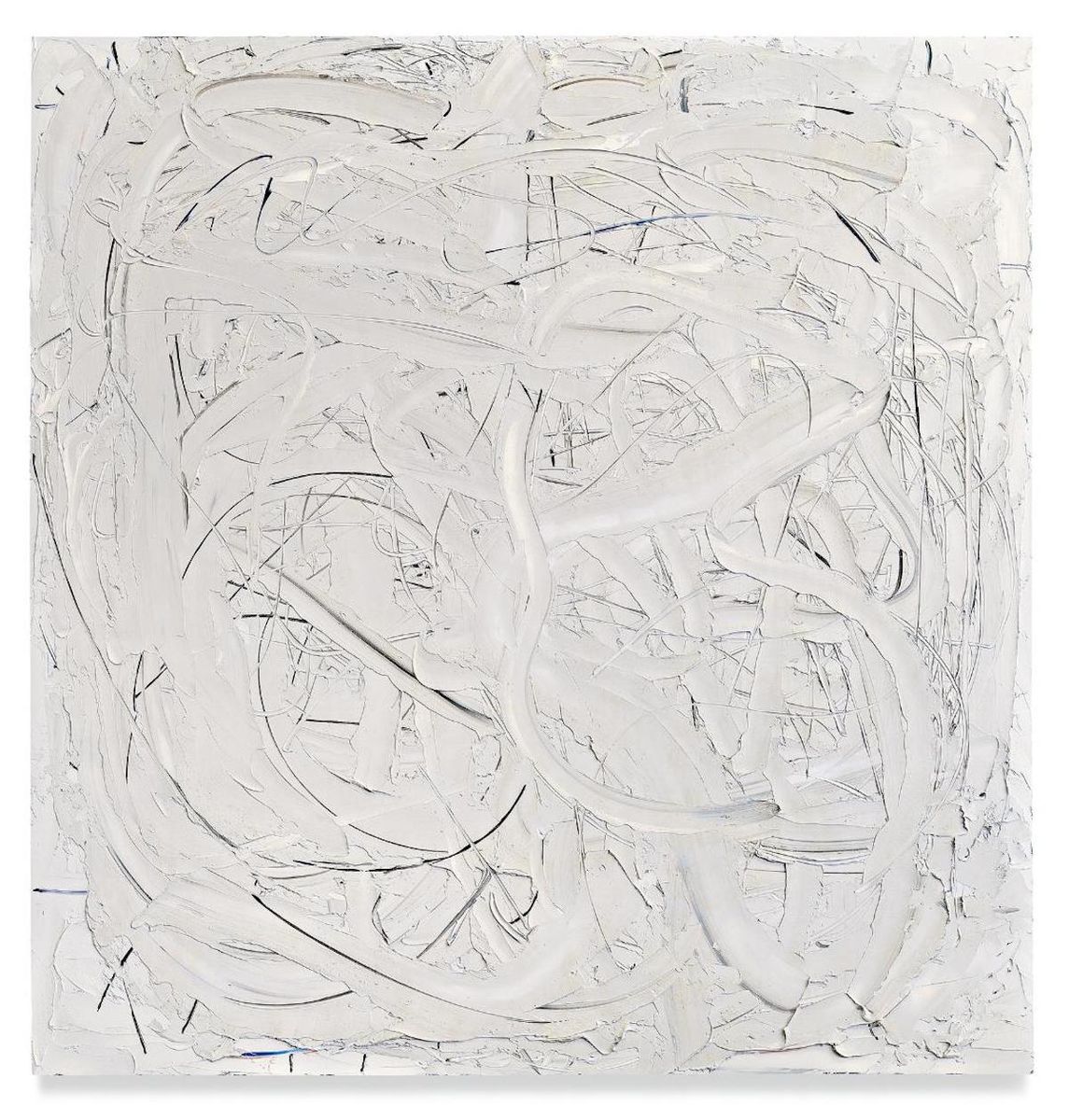

Liat Yossifor, “Portrait II" (2021), oil on linen, 80 x 60 inches

Yossifor’s paintings are dense with contradictions. They invite viewers to see figural presences that never become pictorially apparent but are sensed throughout her work, in both their texture and the sensuous, linear shapes defined by swirling swaths of paint, the result of what the gallery press release calls “surrealist automatic drawing techniques.”

The exhibition’s title comes from André Breton’s 1932 book Les Vases communicants (The Communicating Vessels), which was partially inspired by Sigmund Freud’s writings about dreams and dreaming, and the connections between the interior imagination and everyday facts. By using this title, Yossifor suggests she believes that paint enables viewers to recognize connections between the imagination and the ordinary world without relying on the overtly pictorial.

The exhibition includes seven human-scale, vertical rectangular works. All the paintings are between 80 and 82 inches tall and vary in width from 60 to 78 inches — measurements that indicate their scale was determined by the artist’s reach. In this sense, we might regard the paintings as portraits of figural actions, rather than of figures.

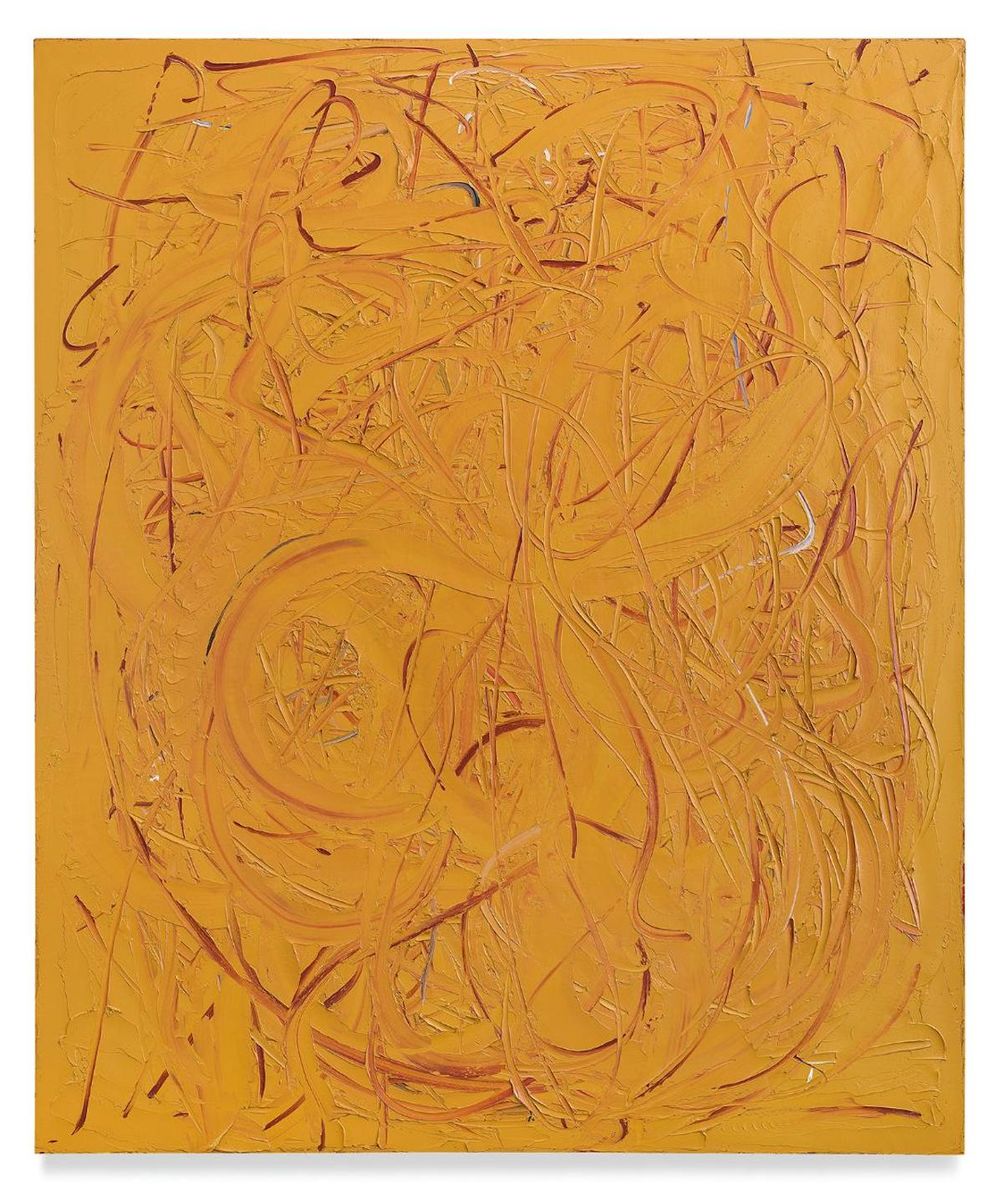

Liat Yossifor, “Solar" (2021), oil on linen, 82 x 68 1/2 inches

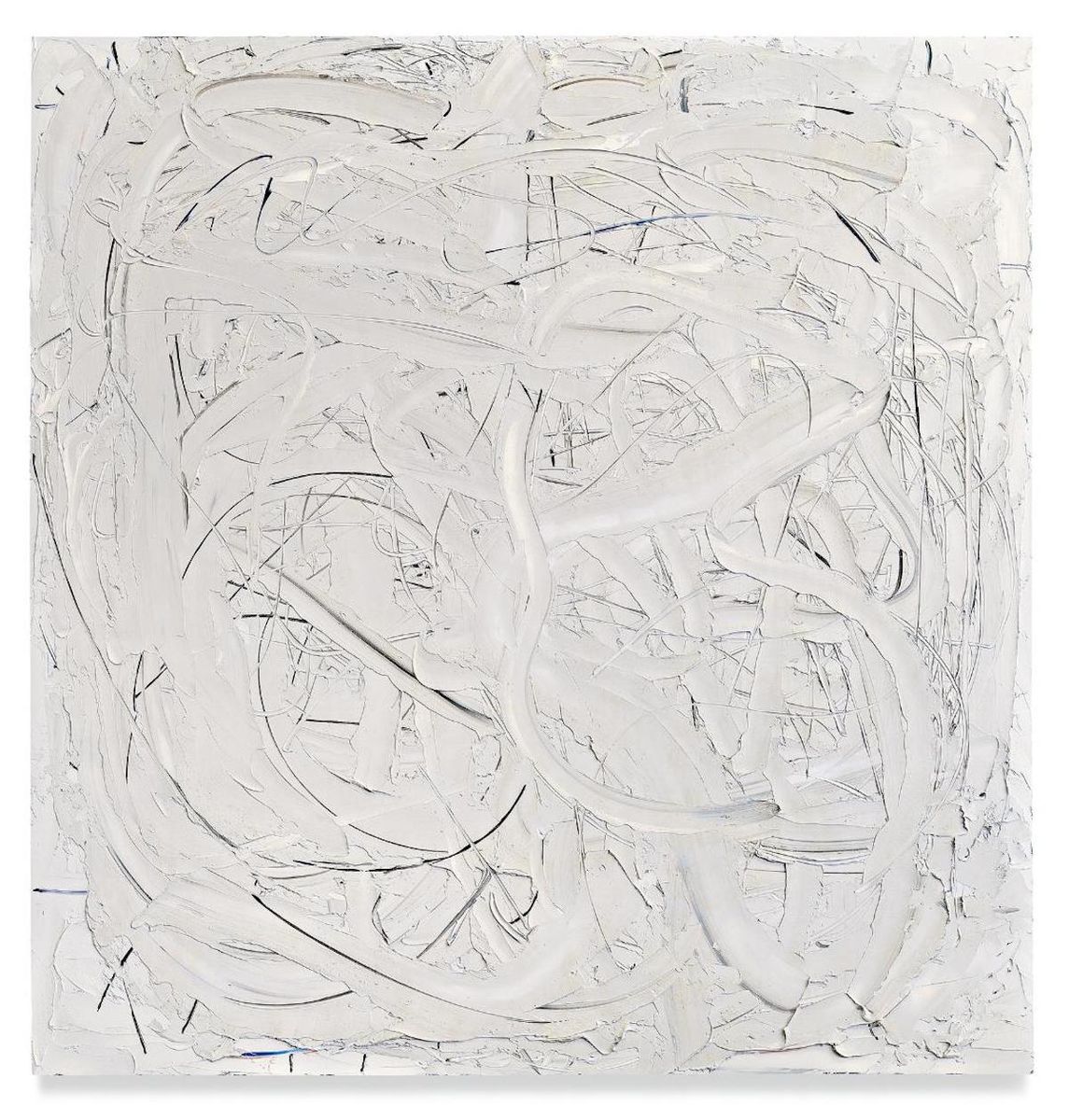

While viewers are likely to perceive the works as monochromatic, Yossifor has painted each with an undercoating of at least one color. After adding palpable layers of paint, she goes back into the surface with various instruments of different widths. Her process entails building up a painting with an impasto skin and them digging into it, caressing and scratching.

“Portrait I” (2021) reveals traces of blue, brown, white, and a bit of brownish-red in the gouges running through the paint. The gouges and swath of paint are held in check by paths of thick, creamy paint that often run parallel with the painting’s physical edges, serving as a border between what is outside and inside. Within that border, the surface becomes an interlocking, overlapping swirl of paint paths and deep gouges, a controlled series of movements that approach an ecstatic state without ever arriving at frenzied release.

There is a top and bottom to these paintings that is inflected by Yossifor’s acknowledgement that the gestures have to stay within the painting’s physical borders. All of the works contain circular and S-shaped swaths, which evoke a female figural presence that never fully coheres. It is as if the figure is at once emerging from and merging with the paint. This state of transition — of simultaneously appearing and disappearing — does not seem to me purely aesthetic. Rather than resolution, we engage with a state of constant transition without, as Yossifor says, “relief.”

Liat Yossifor, “Wide Grey" (2020), oil on linen, 81 x 78 inches

I think Yossifor’s use of industrial grays, black, and dark yellow-ochre as the dominating colors in her work denies any associations with flesh, but it does evoke building materials, such as concrete, onyx, and earth. Her paintings are urban abstractions that tacitly recognize the pressure of anonymity that is integral to the people working in office buildings. The works evoke walls and plastering, as well as the human desire to leave behind one’s permanent mark. The surface shifts — from smooth, creamy pathways to deep gouges — imbue the paintings with an object-like tactility, and render the works topographies sensitive to changing light.

At time when our collective anxieties are pushing for solutions, Yossifor reminds us that answers are likely to be temporary, while change is inescapable. Where that change will lead us cannot be predicted. By working with a wet, viscous material, and making artworks within what is presumably a circumscribed time period, Yossifor becomes a diarist who refuses to tell stories.

Liat Yossifor: Communicating Vessels continues at Miles McEnery Gallery (520 West 21st Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through June 19.