Carmen Winant Fortnight Institute

Artforum / Jan 1, 2021 / by Zoë Lescaze / Go to Original

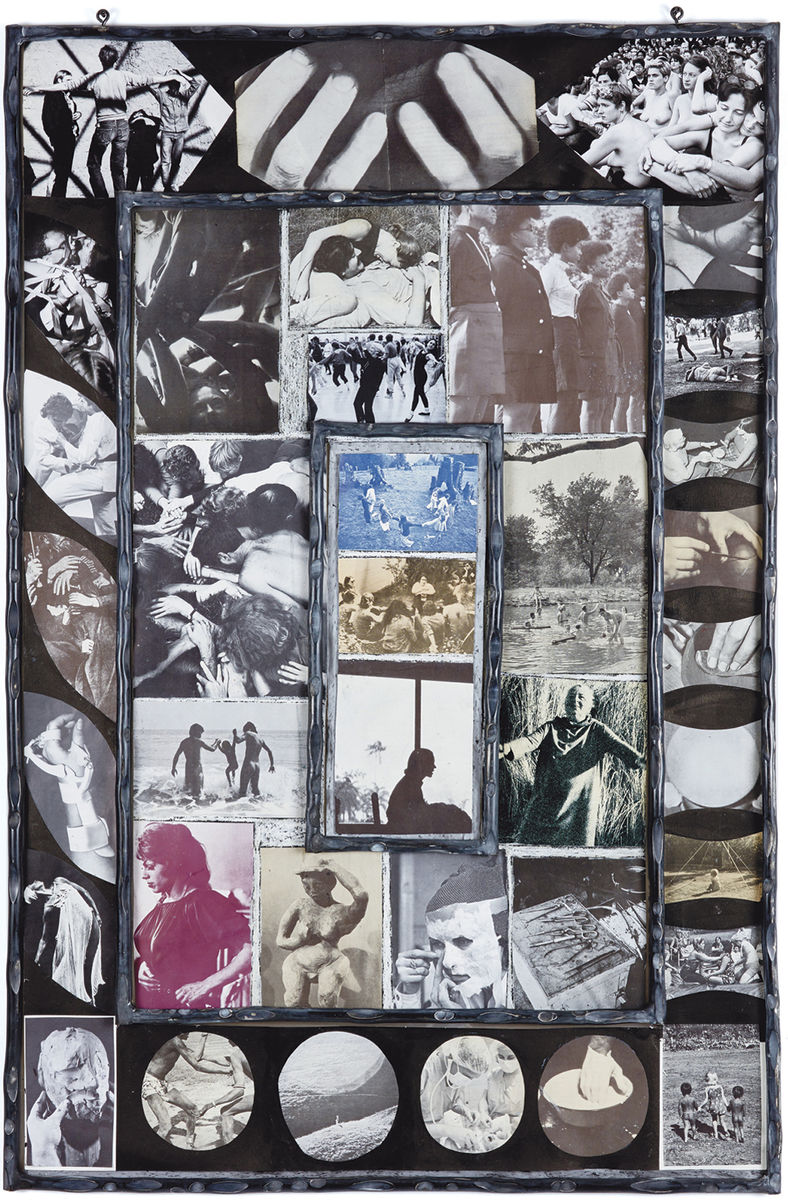

Carmen Winant, Togethering 9, 2020, oil pastel, found images on paper, sumi ink, aluminum frame, 41 × 27”.

Touch is our first teacher. Long before language takes hold, we absorb lessons in pleasure, pain, comfort, love, and fear through our skin. Despite its primacy in our early lives, however, touch remains one of our least appreciated senses—a function, perhaps, of its Western reputation as a “primitive” or “feminine” means of perception, a second-class citizen to the supposedly more rational faculties of sight and hearing. The vital but marginalized nature of touch provided a rich subject for Carmen Winant, an artist whose work often concerns bodies, particularly those of women, and their portrayal. Winant is best known for My Birth, 2018, an astonishing installation comprising two thousand photographs of women in labor, depicting a universal phenomenon that, nonetheless, rarely appears on the walls of art museums. For her exhibition at Fortnight Institute, Winant presented kaleidoscopic collages exploring the body as border zone, the boundary that both delineates us from and allows us to commune with others.

To create the twelve works on view here, Winant culled mostly black-and-white pictures from 1960s (or thereabouts) books on feminism, healing, and spirituality, cut them into irregular triangles, squares, diamonds, petals, and disks, and arranged them on steel plates in patterns inspired by new age mandalas. Photos of people dancing, stretching, drumming, embracing, and bathing outdoors—alongside pictures of nudist groups, therapeutic rituals, nursing infants, outstretched arms, upturned faces, and countless hands—formed concentric grids and pathways within notched aluminum frames. Touch was closely linked with the act of creation in these works: Several pieces included images of ceramic vessels, figurines, or fingers pinching clay. Additional photographs, some cut into the shape of hands, dangled from the bottom edges of other pieces, lending them a sense of talismanic folk magic, like protective amulets one might hang above a threshold or tuck beneath the bed of a loved one. Executed less capably, these collages might have simply registered as hippieish celebrations of physical contact, but Winant infused them with a sense of ambivalence through the presence of more ambiguous elements—a set of gleaming calipers and medical scissors in one work, a head completely mummified in surgical gauze in another, a young demonstrator being dragged from a crowd by police officers in a third. Even photos of presumably consensual touching—five men bent over a nude woman lying on the floor, for instance—took on an unnerving quality amputated from their original context. Our bodies, Winant reminded us, are still battlegrounds.

In an age when images are so easily found online and digitally combined, Winant’s decision to amass a tangible archive and manipulate her source material by hand reflects a conspicuous conviction in the advantages of tactile experience. Her appropriation of existing images aligns her somewhat with Pictures Generation artists, who incorporated found photographs in their work as emblems of broader cultural values, ideals, and desires. The output of these older artists, however, tended to be cool, cerebral, and often ironic—executed with impersonal precision. When the late Sarah Charlesworth selectively excised portions of magazine photos, for instance, she did so with meticulous, clinical exactitude. Winant, in contrast, embraces idiosyncrasies and accidents, and even goes so far as to draw between the elements in her collages with black, silver, blue, and red oil stick, creating a sticky connective tissue. The errant swerves of her scissors become equally part of the work, imbuing it with a dynamic expressive quality lacking in the work of her more calculating forebears. Winant has been described as “a photographer who does not author her own pictures,” but perhaps it is just as accurate to say that she represents an alternate school of appropriation art (Pictures Generation X?) in which cultural critique and the vagaries of the handcrafted are not mutually exclusive. Winant began this series before the pandemic, when she “had no idea that the ground that held it together—togetherness, bodies physically touching other bodies—would shift beneath us,” according to a statement accompanying the exhibition. These works are a means of meditating on that shift, of considering what occurs when we physically gather and organize, and what is lost in isolation.