How to View a Solar Eclipse: Both And at Tiger Strikes Asteroid

Sixty Inches from Center / Dec 10, 2021 / by Annette LePique / Go to Original

Image: Panorama shot of Tiger Strikes Asteroid gallery wall. Five canvases of varying sizes are hung in a measured distance from one another, centered by a horizontal axis. Between the two canvases furthest to the right of the image is a linear sculptural object positioned upon that same axis. From left to right: the left most canvas is a sculptural sketch of the outlines of a bodily form composed with graphite, the second a minimalist picture plane halved into two varying shades of pale green, the third an abstract vista composed by geometric forms in shades of neutral earth tones and jeweled blues, the fourth a delicate sculptural object with a single aluminum horizontal extension, the fifth an abstract picture plane in hot oranges, yellows, and sands, with the final canvas a small graphite sketch with text and a centered linear form. Photo credit: Tom Van Eynde.

Both And at Tiger Strikes Asteroid explores the ambiguities of these folded, Möbius strip topographies in contemporary work by artists Alex Chitty, Julia Fish, Avery Z. Nelson, and Brittney Leeanne Williams, alongside abstract paintings by the Chicago-based artist Miyoko Ito. Curated by Nicole Mauser, and in partnership with The Smart Museum of Art, The Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events, and Art Design Chicago Now, the exhibition both traces and cultivates a dialogue between these contemporary artists and Ito through their use of color, time, form, and space. This relationship imparts a sense of play and expansion to the frames of psychic and physical space, the figure and its exterior edges soften, shift, and blend together. Each piece plays with ideas of representation and abstraction till there is a moment a revelation, of breakdown. This is not a relationship of either or, there is a generosity of expression, it is a space of abundance, it is what it means to be Both And. As these edges move and grow, as they are seen and hewn, again and again, a breakdown can become something different, something new.

Ito lived in the Japanese countryside with maternal family members during the years 1923 to 1928. The artist fell ill with a mysterious illness for most of that period in her childhood and was unable to walk. While there was never a confirmed diagnosis, years later Ito herself hypothesized that “it was probably a childhood nervous breakdown.” Throughout her life, Ito’s relationship to her internal life was one of friction, complexity, and contradiction—relatable entanglements for any artist creating within systems of oppression, enduring trauma, and challenging what possibility can mean. Ito rarely spoke about the time she and her husband were forcibly interned by the American government and once released she dedicated most of her adult life to raising her children. She turned to painting full-time in her later years which is when she had her second nervous breakdown, about which she stated “finally I did relax and have a nervous breakdown to my heart’s content … I had total control of myself, and I knew what was happening.”

Image: Close up of a two dimensional piece in oil and charcoal on canvas. Delicate charcoal lines are positioned both vertically and horizontally to form geometric elements akin to a modular structure, site, or landscape against a banner of forms outlined in shades of striking coral. Miyoko Ito, “Untitled," 1983. Oil and charcoal on canvas (unfinished), 46 5/8 x 42 in. (118.4 x 106.7 cm). The David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago; Gift of Alan Ichiyasu. Photo credit: Tom Van Eynde.

A break down can become a breakthrough. A break down can be a breakthrough. A breakdown can, will, should, never, undoubtedly, always, forever and a day, pour like iced vanilla soft serve into your waiting palms under a halo of chlorine as the sun squints down like rhinestone rivulets, break through. Now let us try another door.

Peer through the keyhole, look again through the camera’s lens, see the shadows through the hotel window. Here there are layers to meaning, some space both physical and metaphysical cannot, can never, be known. The demarcations of inside and out begin to fold together, representation is never a single being. Your room, your heart, your home. Today it is not your beautiful house, but tomorrow it could be. Relationships between object, actor, and environment are forever made anew. There is overlap here, your sight and our site forever changing. Now let us experiment, let us make something: a contradiction, an ambiguity, a relationship, a newness, a map yet to be unfolded. Both And’s curatorial dialogue between the works by Chitty, Fish, Nelson, and Williams creates a relationship equal part unknown, perplexing, and desirous—what can we make in turn?

Alex Chitty’s “Tabled” series (numbers VI-VIII) are moveable, malleable sculptural pieces that according to the artist can be positioned and re-positioned in a variety of ways. Akin to natural forms, like wheat stalks or reed plants born of stainless steel and aluminum patina, the pieces pose a question of how one engages with their environment. Do you notice, do you see? Ask yourself, how do you move through space? What makes your space, this space? Is it you?

Continuing this line of inquiry, we found ourselves facing the subject of Julia Fish’s practice, their questions, the object of their gaze: the artist’s brick storefront home and studio. The picture plane of “Brick Mirror” is almost bifurcated into two distinct halves. A pale chartreuse, the green of washed dollar bills and 1950s limes, touches the edges, the beginnings, of a heavily outlined rectangular form in cold spearmint. Based on the bricks of Fish’s home studio, the rectangular form sits aloud upon the picture plane. Question how and what you see, what meaning does your gaze impart. It is the bind, the language, the psychic space of abstraction. Think now on language’s failures, its boons, its busts.

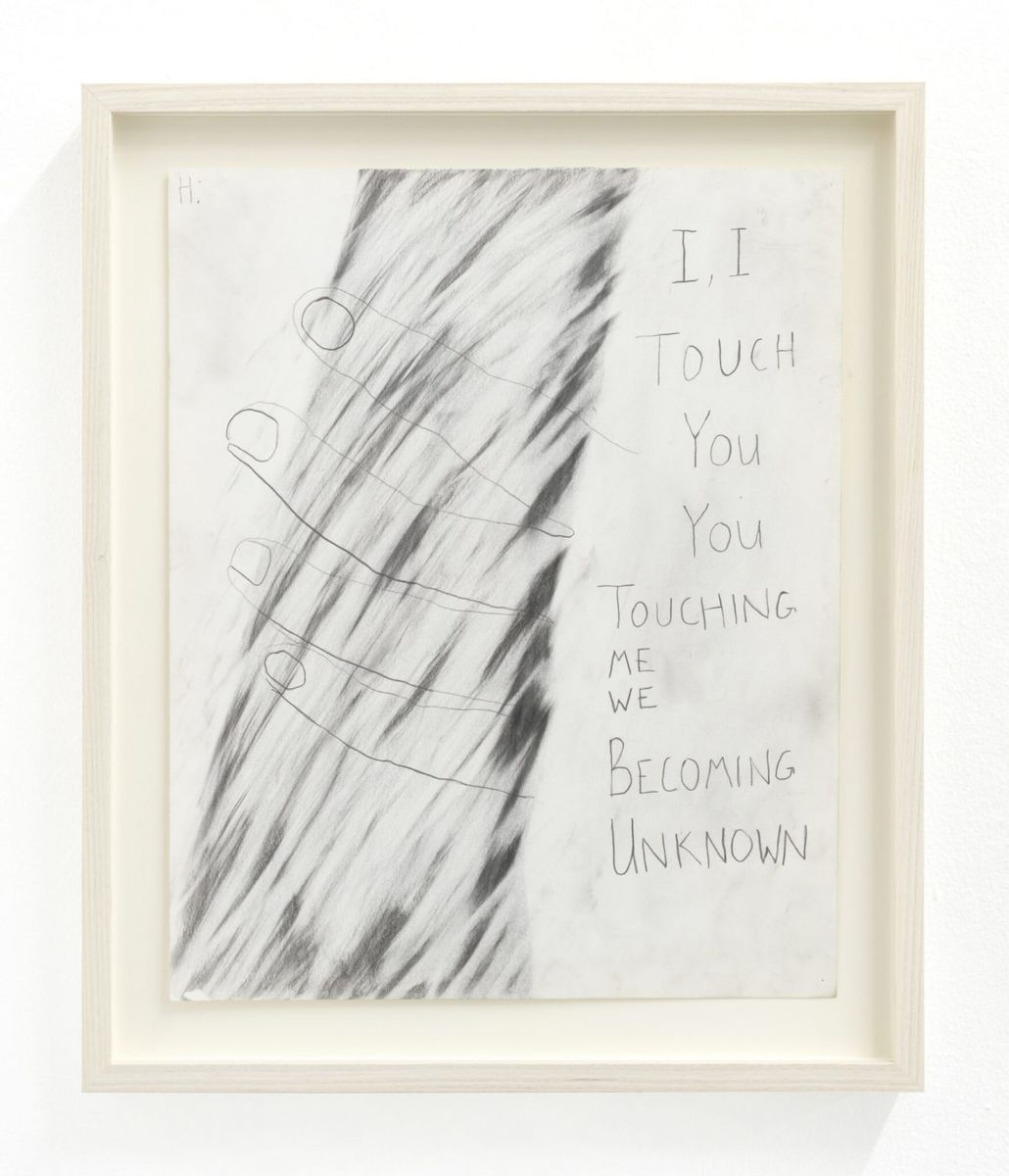

Image: Close up of a two dimensional graphite sketch, with both image and text elements. Text, on the right of the picture plane reads “I I You You Touching Me We Becoming Unknown" in a vertical arrangement. To the left of the text, the outline of a human hand grasps a linear, geometric form shaded with varying degrees of pressure. Avery Z. Nelson, “Becoming Unknown," 2018. Graphite on paper; 11 x 13 in. Photo credit: Tom Van Eynde.

Text has the tendency to reflect, refract, and double back upon itself; it can drip, it can ooze, it can lacerate the tongue. It’s a thing that burns. When you read Avery Z. Nelson’s 2018 “Becoming Unknown”, words trickle down the paper, “I, I touch you you touching me we become unknown” upon a background of smudge, cloud, and shadow. To the left of the text emerges the ephemeral outline of a human hand grasping a thickly spaced linear form composed with undulating graphite shade and pressure. The ghostly appearance of the hand challenges the perceptions of the figure in space. Or does it? Where do I, where do you, where can we end and something else, something new begins?

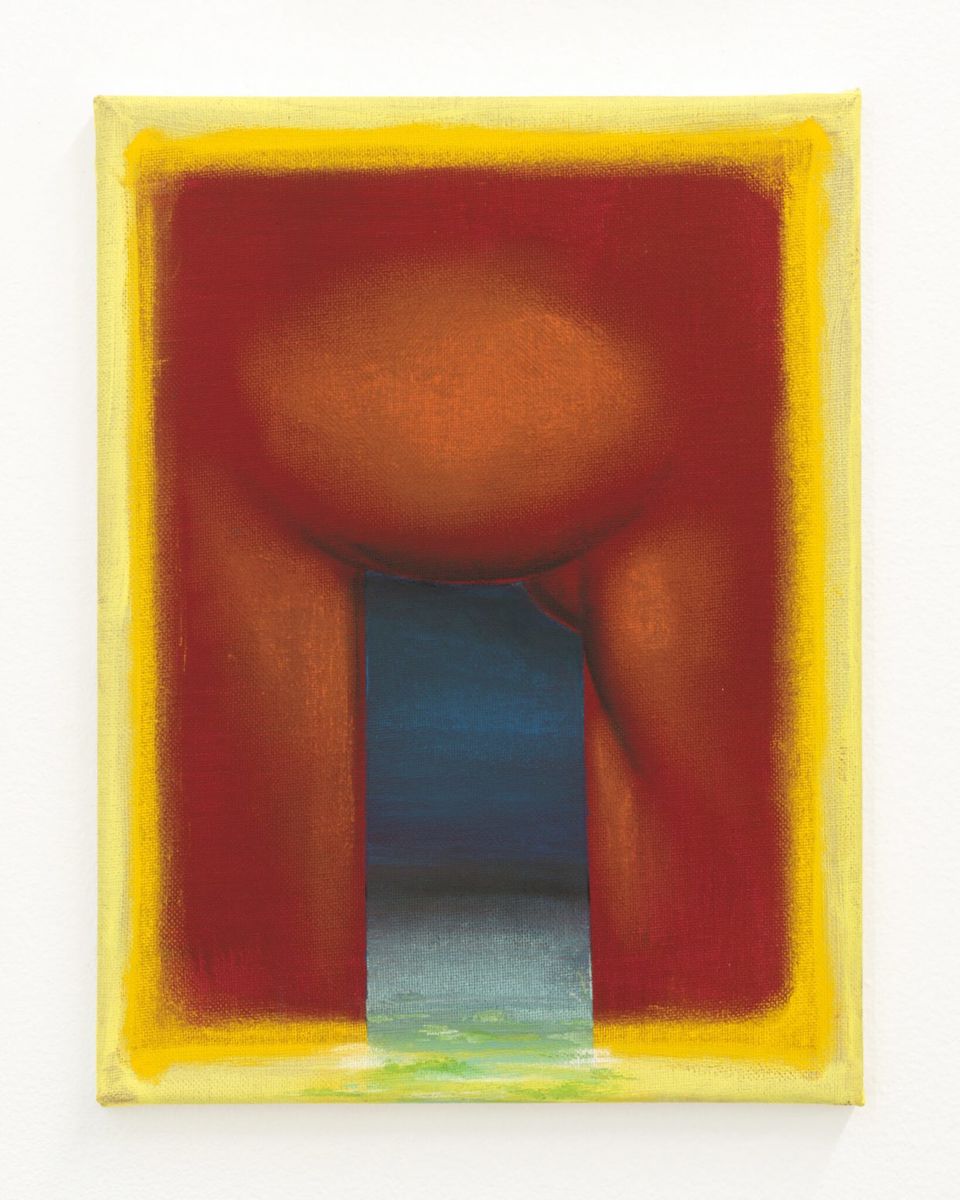

Now you see, it is flesh made manifest. The body pulls like taffy and is born into more and less than the sum of its parts, both a body and not a body. Both I and not I. In Brittney Leeanne Williams’ 2020 “Arch” series, the figure becomes part of the picture plane, till the picture plane is also the figure, both are not one and the same, but the connection is inviolable, undeniable. Where are you looking, where do you end, and I begin? Fluorescent neon reds lick like flames against sputters of dark shadow and ash. Fleshy mounds of muscle and sinew rise upward to form openings, doors, windows, gazes into the mind, into indeterminacy. Puddles of grey-green seawater grate the base of one picture plane while the other is held aloft through the impossible blues of the waking sky. You are the change, the reader, both the text and the work.

Image: Close up of a two dimensional piece with a picture plane outlined in shades of yellow. Within the yellow frame a fleshy, bodily form arches over a dark blue portal. Brittney Leeanne Williams, “Arch 16," 2020. Acrylic and pastel on canvas; 12 x 9 in. Photo credit: Tom Van Eynde

In classical Japanese poetry makurakotoba, meaning “pillow words’, are short phrases that alter the lines that precede and follow their appearance in a poem; they in turn shift the meaning of the poem itself. Makurakotoba are a source and site of reader engagement, they allow for meaning to change and multiple texts to be born. Film critic Noël Burch created the term “pillow shots” to both describe the low-angled shots (akin to the camera resting atop tatami mats) that appear throughout the oeuvre of director Yasujiro Ozu, and directly link Ozu’s practice to the tradition of makurakotoba. In Ozu’s 1949 Late Spring, a poetic domestic drama of father daughter miscommunication, shots of an empty room are interspersed with a main character’s life-changing revelation. In the room, the camera finds and focuses in on a single vase. While there seems to be no explicit connection between the main character and the vase, the appearance of the object, Ozu’s decision to look, and the connection generated by the cuts between character and vase creates a closeness, a relationship. Though questions remain, such as the nature and meaning of the link between character and object, they are now linked.

One of Ito’s own pieces included in Both And, “Untitled” from 1983, is unfinished. Coral strokes of oil fly above thin geometric forms. Delicate charcoal lines shimmer tenuously in heat like the steps of a staircase transformed to a site of escape or ending. Descend or begin your ascension. The choice, the movement, the knowledge is all yours. Breakdowns can be breakthroughs. Think back to Ozu’s vase, looking carries meaning, looking holds meaning, looking, and witnessing make meaning. Let us now see what can be made in a look, in the creation of new spaces, glances, this multitude of untold and unknown stories. What does it mean for you to look, to really see?

Both And is up at Tiger Strikes Asteroid through December 11th. Appointments are recommended.