Jennie C. Jones, a Minimalist Who Calls Her Own Tune

The New York Times / Feb 10, 2022 / by Siddhartha Mitter / Go to Original

A few weeks ago, the artist Jennie C. Jones made her way to the top of the spiral in the Guggenheim Museum to test audio tracks for “Oculus Tone,” a serene, drone-like sound installation she was designing for her exhibition now at the museum.

The space was demanding, with its dome of skylights, recessed exhibition bays and open central volume cascading down. As she worked with Piotr Chizinski, the museum’s head of media arts, decisions became clear: which speakers to use, which sound files to tweak or discard.

“As someone who works with parameters and likes parameters, because it forces you to think in different ways, I love it,” Jones said later. “The riddles are fun to solve.”

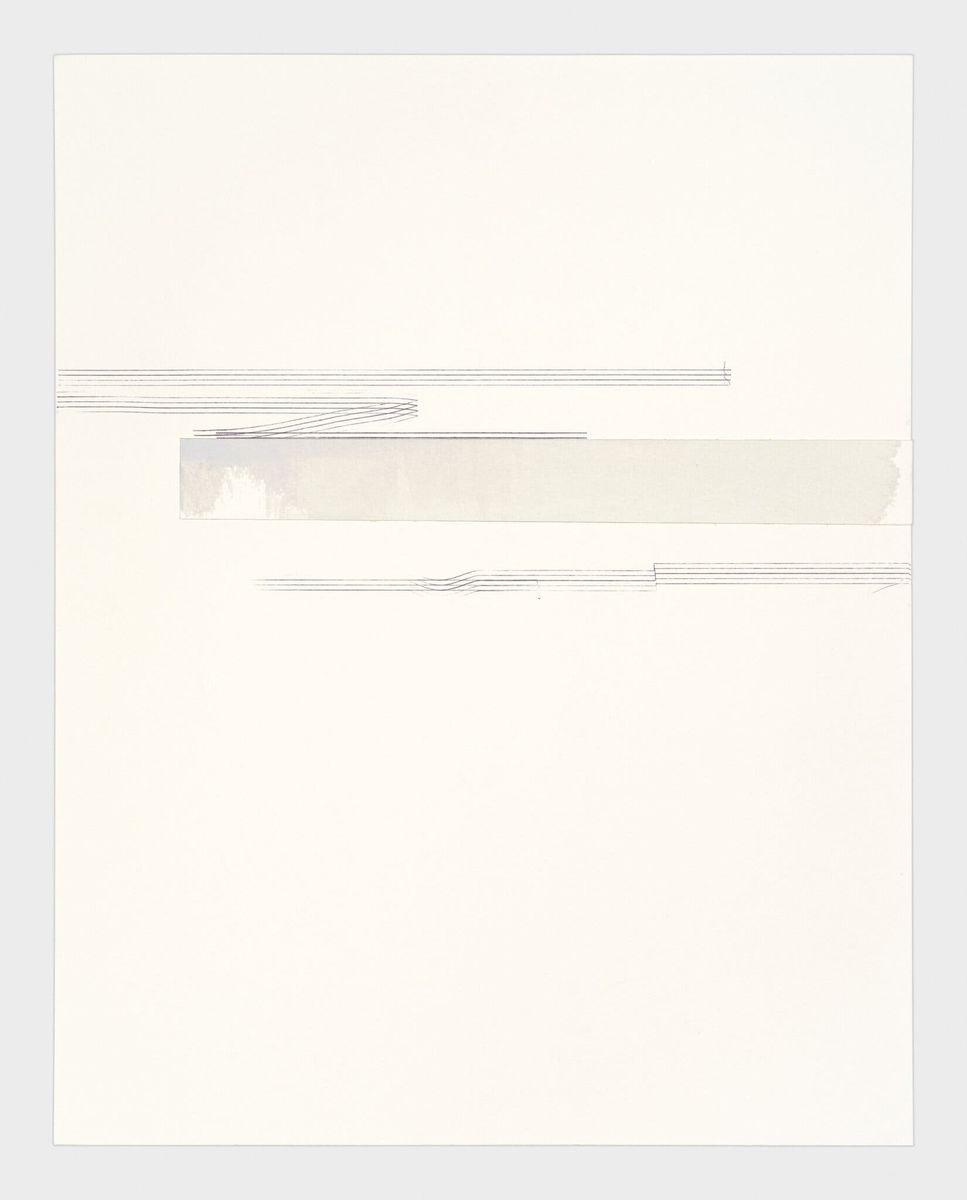

Jones, 53, is an artist who allies sound and shape in more ways than one. She is an abstract painter whose works channel the austerity of Minimalism but incorporate acoustic panels — the kind used in concert halls or music studios — atop the canvas. Her drawings nod to the world of music with elements of sheet-music notation or acoustic waveforms.

“Dynamics," a major New York museum solo exhibition for Jones, includes an audio installation at the Guggenheim’s spiral ramp’s summit that bathes the space in contemplative, drone-like tones.Credit…David Heald/Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

Her audio pieces accord with their settings while subtly challenging them. She filled Philip Johnson’s Glass House in New Canaan, Conn., an essential work of Western modernism, with a hum produced in part by glass and metal singing bowls. In a grand hall in New Orleans that was once home to Confederate artifacts, she overlaid recordings of three choirs performing “A City Called Heaven,” a utopian Black spiritual.

“Dynamics,” Jones’s current Guggenheim exhibition, gathers works in all these forms, in an institution with its own long association to Modernism, from its architecture to its collection and programming. The exhibition is a major New York solo museum presentation for an artist whose practice is as sensory as it is cerebral.

She has long swum against the tide. As a teenager in the Cincinnati suburbs, Jones was a Black kid who was into punk rock. At the School of the Art Institute of Chicago in the late 1980s, she dove into postwar modernism and formed a lasting attachment to abstraction — with a taste for artists like Piet Mondrian, Ellsworth Kelly or Agnes Martin — out of pace with the brewing culture wars and rising interest in art that directly addressed identity and social representation.

In the same period, she immersed herself in the Black sonic avant-garde, from post-bop to contemporary-classical composers and, especially, the field of improvisation-led music that rose in the 1970s around figures like Cecil Taylor or the Art Ensemble of Chicago, and became known as “creative music.” The exclusion of these streams from the history of modernism, as taught at the time, became the creative provocation that has animated her work ever since.

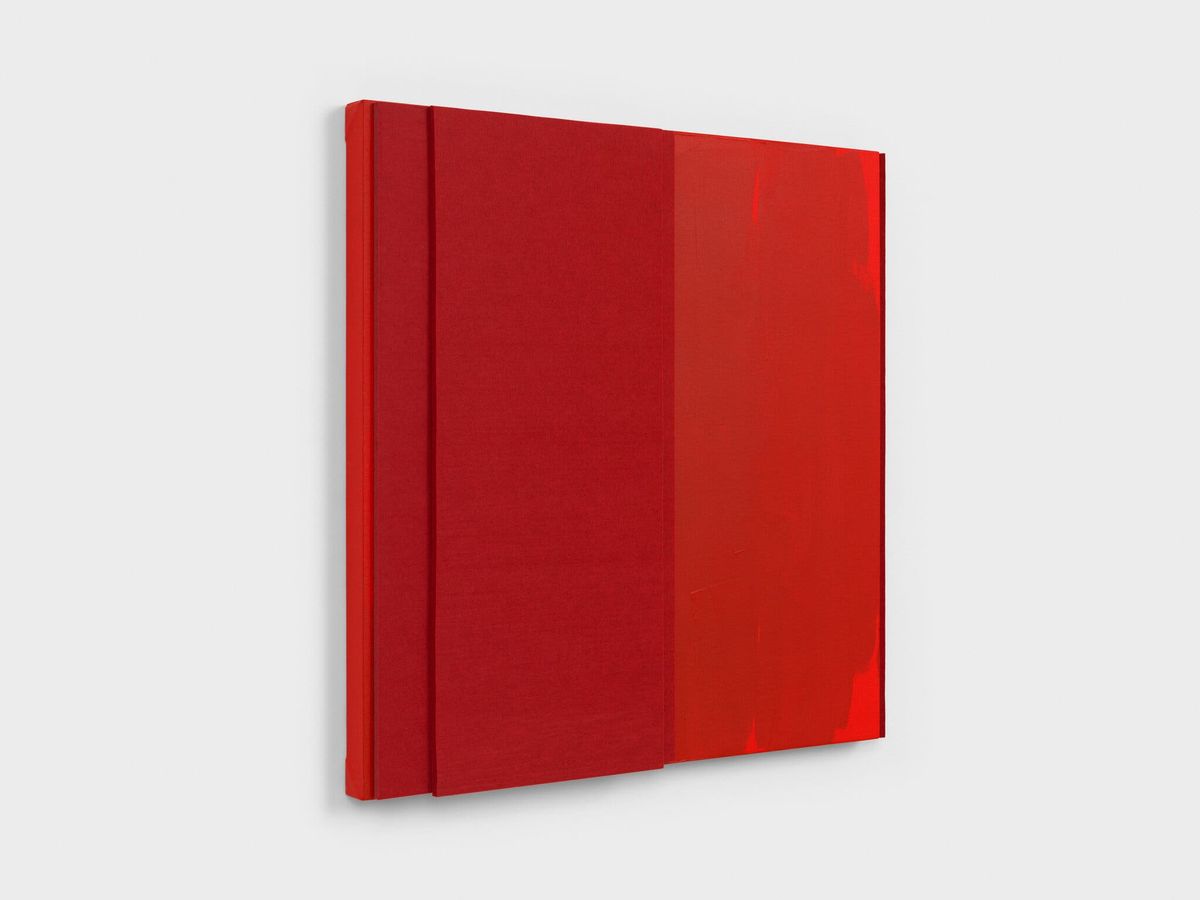

“Red Tone Burst #2," from 2021. Recently, Jones has made bolder use of strong colors in her paintings, notably red, which she previously used as accents and emphasis. Now, she said, she’s bringing the “hot glow to the fore." Credit… Jennie C. Jones/Alexander Gray Associates and PATRON Gallery

These interests placed Jones in a relatively rarefied lineage of Black Modernists who were undervalued in their time, from Jack Whitten or Alma Thomas to the Chicago-based Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians (A.A.C.M.) or the St. Louis-based Black Artists’ Group — networks and collectives that dealt equally in music, art, writing and political thought.

Today, Jones remains out of sync with certain trends — embraced by the market — like the turn to figuration and Black portraiture. But her supporters, who include major musicians and scholars, admire what they see as her prescience and persistence.

The scholar and composer George Lewis, the author of the definitive study of the A.A.C.M., called her “fearless.” “She asserts her right to abstraction,” Lewis said. “I take Jennie as a model for saying, well, you can fight that, and you can win.”

For the poet and theorist Fred Moten, who wrote a text to accompany a recent exhibition by Jones in Chicago, she is in the lineage of Whitten, Thomas or Sam Gilliam in “calling into question the normative ways in which we think about abstraction.” Black abstraction, Moten said, emerges from social existence, as in the “outsider” art of Thornton Dial or the quilters of Gee’s Bend, Ala.

For all the intellectual love, Jones’s work is also meant, more simply, to be felt. Her techniques invite the viewer (or listener) to experience something that isn’t quite captured by either of those senses but somehow addresses both, in a kind of vibrational transfer.

Jones with Lauren Hinkson, associate curator, collections at the Guggenheim Museum, who organized “Dynamics." They likened the way the works are sequenced on the wall to musical phrases. “When you spend time on close looking, you start to hear things," Hinkson said of Jones’s work.Credit…David Heald/Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation

“When you spend time on close looking, you start to hear things,” said Lauren Hinkson, the associate curator, collections at the Guggenheim who organized the exhibition.

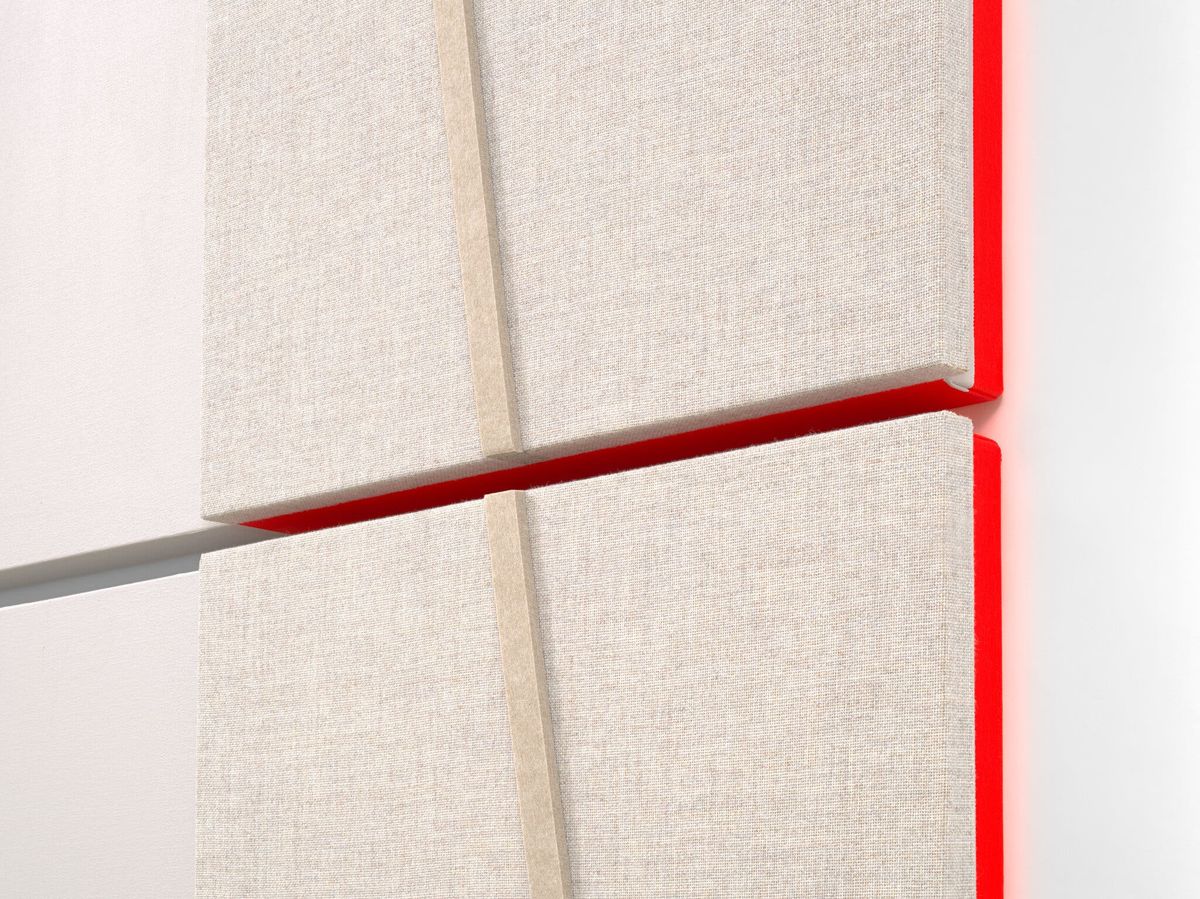

In the paintings it begins with a kind of trompe l’oeil. From afar they seem like color and line studies on canvas, but they are three-dimensional and incorporate acoustic panels — a material that she introduced in a breakthrough exhibition at the Kitchen in 2011. These paintings do not broadcast sound, but they orient it: Their placement in a room shapes how you hear the space.

Another Jones signature is to paint a red or yellow streak on one side of the canvas or its top, perpendicular to the wall, so that when the light hits, a diffuse glow forms. It is a visual effect, yet not that different from an auditory hum.

In the same way, the quick flashes of feedback that streak across the soundscape in “Oculus Tone,” which is installed at the top of the Guggenheim spiral but gently permeates the entire cylindrical volume, bear some affinity to the sharp streaks of color that cross the monotone surface of some of her paintings, installed on the spiral’s lower levels.

It is a matter of suggestion, ultimately up to each person’s own eyes and ears. “I feel like there are multiple entry points,” Jones said. “I hope there’s some poetry and feeling and nuance.”

“Fractured Extension/Broken Time," 2021 (detail). Up close, Jones’s paintings reveal themselves to be three-dimensional, incorporating acoustic panels — which affect the way sound and voices move in the room — and architectural felt. She often paints a red or yellow line along the side of a canvas, producing a diffused glow on the wall.Credit…Jennie C. Jones/Alexander Gray Associates and PATRON Gallery

On a frigid day recently, Jones, who is a vivacious and engaging conversationalist, offered a visit to her studio in Hudson, N.Y. She moved to the town in 2018, purchasing a small house after living as a renter for over two decades in New York City — mostly in Fort Greene, Brooklyn.

Though she has earned recognition — the Joyce Alexander Wein Prize of the Studio Museum in Harlem in 2012, and exhibitions at the Hirshhorn Museum in 2013 and the Contemporary Art Museum Houston in 2016 — her career has not been lucrative. Her gallery representation has been intermittent, and she has taught part-time at Bard College and the Yale School of Art.

She moved upstate the year she turned 50. “It was time for a reset,” she said. She joined the highbrow Alexander Gray Associates gallery. “Jennie’s career is an object lesson,” said Gray, the gallerist, “in being an authentic artist and operating outside the framework of the market.”

Jones works alone; she even tried to make acoustic panels but reverted to buying them commercially — “Fiberglas is a nightmare, it’s toxic and horrible,” she said. She produces her sound pieces on the Audacity free software, preferring to keep the work simple, without filters or complex effects. She paints on the floor, “listening to music and dancing around.”

Though her pieces for the Guggenheim had already traveled, she had hung other works that exemplified her recent “leaps in materials, and pushing and thinking of paint in different ways.”

Jones moved to Hudson, N.Y., in 2018 after many years in New York City. She enjoys working on the floor in the studio — a joyful process, she said, “listening to music and dancing."Credit…Lauren Lancaster for The New York Times

She is now applying lengths of architectural felt onto her paintings. “It’s another material to play with,” she said. She can paint onto it, so that it can be either surface or mark. But she is also producing some pure paintings without panels or other accouterments at all.

“I love painting and I hate painting,” she said. She long felt burdened by its role in the grand narrative of art history, and more interested in paintings as objects. Her new monochrome works are ones that her younger self, she said, might have found self-indulgent.

A new bright red piece brought the “hot glow to the fore,” she said. “I’m crawling away from gray.” On the white underpainting for a composition in progress, she pointed to the turbulent strokes and impasto — a contrast with the discipline of the finished works.

“There’s this private expression that happens,” she said. “It starts incredibly free and gestural, and then it’s a process of taking away the mark. In a sense, I feel like I can have it all.”

There is a similar freeing at work in the way that Jones approaches music as a material.

“A Score for Tenderness and Grace," 2021, a collage from a set of 10. Drawing and collage are another method by which Jones invokes the presence of music, with elements that echo, for example, sheet music, notation, or acoustic waveforms. Credit…Jennie C. Jones/Alexander Gray Associates and Patron Gallery

She still refuses to call herself a musician: “I quit piano,” she said. “I quit violin.” She prefers “pretend musicologist nerd.” Though she listens and researches deeply, the epiphany that put music at the center of her art-making came more simply, when some 20 years ago she realized she put effort into selecting music to work as much as she did into her drawings and paintings.

In the 2000s, Jones often made small sculptures using objects associated with music-listening — earphones, cassette cases, CD racks — and drawings on these themes. But as those items disappeared in the transition to digital music, she moved away from this language rather than cultivate it for nostalgia. Her sculpture is mostly sonic now, in her site-specific audio installations.

“I feel like my work is more courageous now,” Jones said. “I feel like I’m in my own skin.” But she still isn’t gunning for the mainstream. She learned from the avant-garde cats that to operate from the edges is also a choice: “It’s not like I’m working at the margin because I’ve been placed there,” she said. “As much as I’ve always been the weirdo on the periphery, I’m happy here.”

Banner image:

Jennie C. Jones in her studio in Hudson, N.Y., with recent works. The artist, who takes her inspiration from the history of Modernism and the Black sonic avant-garde, has a solo show, “Dynamics,” at the Guggenheim Museum.Credit…Lauren Lancaster for The New York Times