With strong showing by Latin American artists and galleries, Expo Chicago expands the definition of a regional fair

The Art Newspaper / Apr 8, 2022 / by Daniel Cassady / Go to Original

The Exposure sector at this year’s fair, curated by Humberto Moro, foregrounds Latin American galleries and serves as a gateway into global conversations.

The description “a regional fair” can seem at best dismissive and at worst derogatory. Expo Chicago, with its wealth of international programming that sees galleries, curators, institutional directors and attendees from across the globe descend upon the Jewel of the Midwest, reimagines what it means to be regional.

Instead of exemplifying an exclusive definition of the word “regional”, this year’s Expo Chicago fair is very much inclusive and expansive. This fact is made clear by the fair’s Exposure section, which was curated Humberto Moro, the recently named director of program for the Dia Art Foundation. In organising the section, Moro focused his curatorial lens on Latin American galleries and artists that could, in turn, underscore issues like labour rights, social and environmental justice, and the influence of technology on the world, all of which should be considered global concerns.

“You have to use the term ‘curating’ loosely in a fair environment,” Moro says, “in the sense of all the limitations there are the ways in which you can articulate an idea through a fair section.” To accomplish his goal, he drew inspiration from the practice of acupuncture, or what Moro called “the idea that there are specific points of pressure that represent not only themselves, but that also represent a network of ‘pressure points’” that can be used to discuss global concerns.

Of the 40 galleries participating in Exposure, which focuses on galleries ten years old and younger, six are from Latin America. Bogotá, Lima and San Juan, Puerto Rico are all represented. There are also three galleries from the flourishing scene in Mexico City. But Moro’s notion of a “network” does not end there. The Chicago-based gallery Paton is showing two Latin American artists, Caroline Kent and Noé Martínez, who share a thematic tie with work that explores their distant and not-so-distant pasts. The Pill, a gallery based in Istanbul, is featuring work by the Mexican conceptual artist Pablo Dávila alongside the Danish French painter Eva Nielsen.

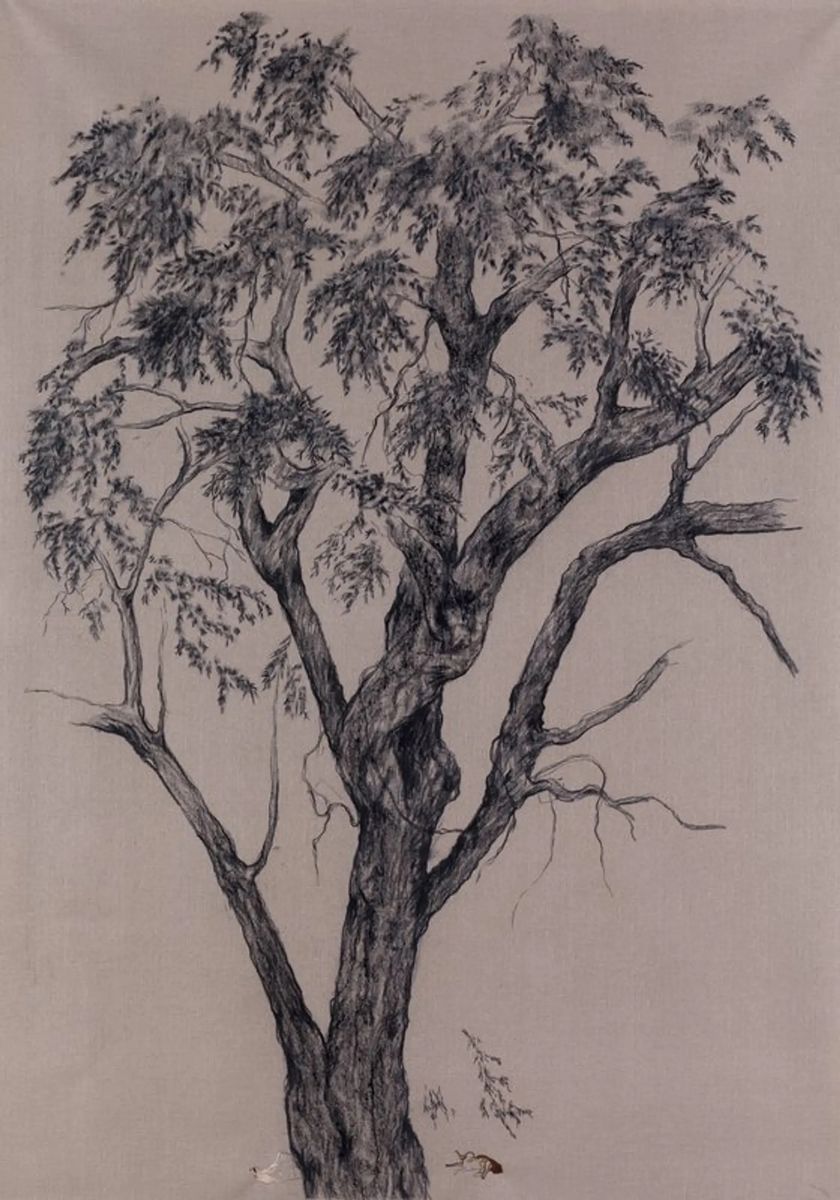

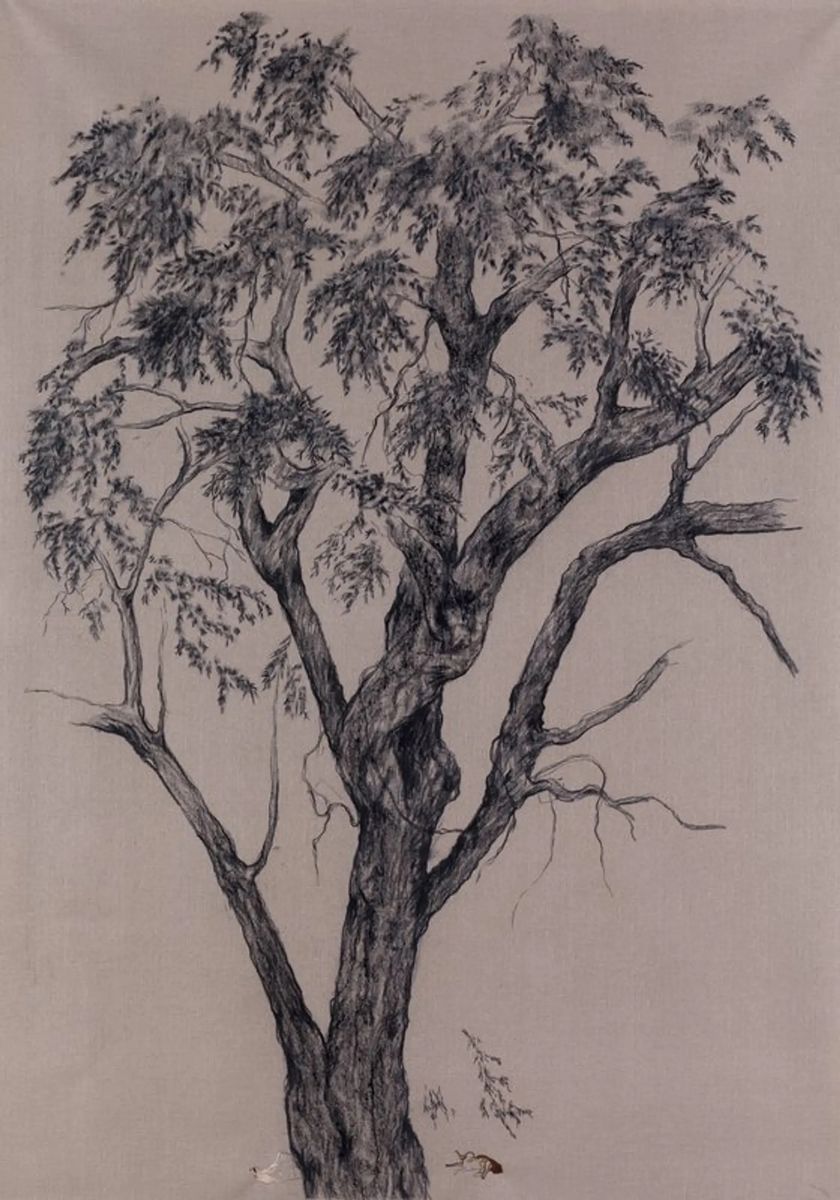

The themes taken on by these Latin American galleries can be specific to those regions, Moro says, like the disastrous effect of narco trafficking on the environment in Bogotá, which is elegantly portrayed with large-scale charcoal drawings on canvas by the artist Nohemí Pérez on view at Instituto de Visión’s stand. The drawings feature specific species of trees, intricately formed and ancient-looking, that have been both witness and victim to the demolition of forests in Colombia for the sake of planting coca. But at the same time, those themes connect with the works by Paolo Cirio and Dread Scott, both of whom deal with the history of slavery and image circulation on Berlin gallery Nome’s stand.

“There is a wider conversation and I think that the section really works as a thermometer of what’s happening around you in young galleries,” Moro says. “It’s like taking the pulse of contemporary creation, through these mechanisms.”

That radiating dialogue was evidently overheard by representatives of the strong institutional presence at the fair. Three works by Pérez from Instituto de Visión were among the few chosen to win the Northern Trust Purchase Prize, which this year led to works being acquired from the fair by the Portland Art Museum in Oregon, Pérez Art Museum Miami and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

“It’s so important for these kinds of works and these kind of artists, that are so underrepresented, to go to a museum like the Portland Art Museum,” says Omayra Alvarado-Jenen, one of the co-founders of Instituto de Visión. “The truth is we have very different audiences and they live a totally different reality to what we experience back home. So it’s important for Nohemí and for practices like this to get that platform, to go to these kinds of museums. And it’s very important that curators are looking for these kinds of works that are looking to bring these narratives back.”

Nohemí Pérez, El Palmar No.4 (2022), which was acquired at Expo Chicago 2022 by the Portland Museum of Art; Courtesy Instituto de Visión

The description “a regional fair” can seem at best dismissive and at worst derogatory. Expo Chicago, with its wealth of international programming that sees galleries, curators, institutional directors and attendees from across the globe descend upon the Jewel of the Midwest, reimagines what it means to be regional.

Instead of exemplifying an exclusive definition of the word “regional”, this year’s Expo Chicago fair is very much inclusive and expansive. This fact is made clear by the fair’s Exposure section, which was curated Humberto Moro, the recently named director of program for the Dia Art Foundation. In organising the section, Moro focused his curatorial lens on Latin American galleries and artists that could, in turn, underscore issues like labour rights, social and environmental justice, and the influence of technology on the world, all of which should be considered global concerns.

“You have to use the term ‘curating’ loosely in a fair environment,” Moro says, “in the sense of all the limitations there are the ways in which you can articulate an idea through a fair section.” To accomplish his goal, he drew inspiration from the practice of acupuncture, or what Moro called “the idea that there are specific points of pressure that represent not only themselves, but that also represent a network of ‘pressure points’” that can be used to discuss global concerns.

Patron stand Installation view, EXPO: A Tapestry of Lost Architectures; Photography: Timothy Johnson

Of the 40 galleries participating in Exposure, which focuses on galleries ten years old and younger, six are from Latin America. Bogotá, Lima and San Juan, Puerto Rico are all represented. There are also three galleries from the flourishing scene in Mexico City. But Moro’s notion of a “network” does not end there. The Chicago-based gallery Paton is showing two Latin American artists, Caroline Kent and Noé Martínez, who share a thematic tie with work that explores their distant and not-so-distant pasts. The Pill, a gallery based in Istanbul, is featuring work by the Mexican conceptual artist Pablo Dávila alongside the Danish French painter Eva Nielsen.

The themes taken on by these Latin American galleries can be specific to those regions, Moro says, like the disastrous effect of narco trafficking on the environment in Bogotá, which is elegantly portrayed with large-scale charcoal drawings on canvas by the artist Nohemí Pérez on view at Instituto de Visión’s stand. The drawings feature specific species of trees, intricately formed and ancient-looking, that have been both witness and victim to the demolition of forests in Colombia for the sake of planting coca. But at the same time, those themes connect with the works by Paolo Cirio and Dread Scott, both of whom deal with the history of slavery and image circulation on Berlin gallery Nome’s stand.

“There is a wider conversation and I think that the section really works as a thermometer of what’s happening around you in young galleries,” Moro says. “It’s like taking the pulse of contemporary creation, through these mechanisms.”

That radiating dialogue was evidently overheard by representatives of the strong institutional presence at the fair. Three works by Pérez from Instituto de Visión were among the few chosen to win the Northern Trust Purchase Prize, which this year led to works being acquired from the fair by the Portland Art Museum in Oregon, Pérez Art Museum Miami and the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis.

“It’s so important for these kinds of works and these kind of artists, that are so underrepresented, to go to a museum like the Portland Art Museum,” says Omayra Alvarado-Jenen, one of the co-founders of Instituto de Visión. “The truth is we have very different audiences and they live a totally different reality to what we experience back home. So it’s important for Nohemí and for practices like this to get that platform, to go to these kinds of museums. And it’s very important that curators are looking for these kinds of works that are looking to bring these narratives back.”