Review: Jamal Cyrus at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth

Glasstire / May 2, 2022 / by Betsy Lewis / Go to Original

Visual artists use an indirect vocabulary composed of the elements we’re taught in Art 101, and it puzzles a lot of people, but for us who make art (or like it enough to read this website), the act of looking, and consequently seeking, another person’s visual vocabulary is pretty thrilling. And when you get it, even as you doubt that you are, it can result in a pure communion that most churches can only aspire to.

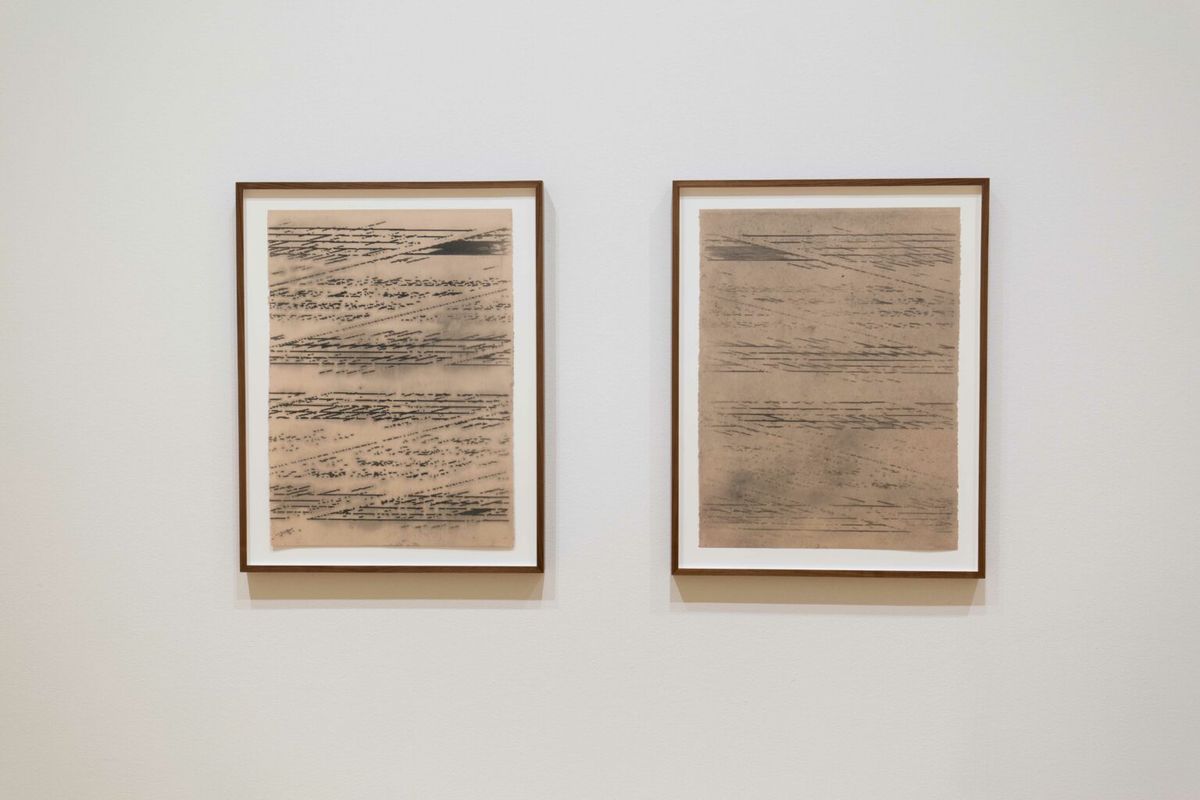

Jamal Cyrus, “Rite_1-Percussion Ballad," and “Rite_1-Percussion Ballad (reverse low pass gate)," 2022, Graphite powder on paper, Unframed: 30 × 20 inches, Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago

In Focus: Jamal Cyrus at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth, the Houston-based artist argues with America’s rendering of the Black contribution to its historical margins. Although this argument is (or should be) by now a frequent topic of national discourse, Cyrus attacks the theme as if a new Harlem Renaissance, made for our times, were embodied in a single man.

To be clear, I am a white writer writing about artwork born of the Black American experience. I will never live a single moment of what it means to be Black in this country. But art gives us an opportunity to learn, so I approach this review with my customary formal analysis, and without pretense of interpretation on topics I have not lived. Cyrus chooses materials that are part of everyone’s daily existence — like denim, and music — and his choices grant access for all to this exhibition.

Jamal Cyrus, “Blue Alluvial Glue (Shape)," 2022, Denim, cotton thread, cotton batting, and metal, Overall: 56 × 42 inches. Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago

In Blue Alluvial Glue (Shape), asymmetrical denim straps advance down a canvas pieced together from scraps of rough off-white cotton. It is threadbare and layered. It exposes patches and pockets that link to the personal, an intrusive experience considering the part played by American denim. It protects our flesh on the daily, and it knows no demographic. This work’s unique pieces look affected by several lifetimes, witnessing one last life on a wall inside one of the nation’s best museums. It’s an unlikely swan song for a stack of old jeans. Blue and indigo swatches strike the canvas vertically in a distinctive mass, like a body, a torso, a head, an arm. Is it falling? Or upside-down? Loose threads bunch together, interrupting the canvas’ makeshift geometry. How many lives has this denim lived? How has it remained physically detached from the bodies it clothed? In the operational environment of a fancy art space, how does it conjure the hands that did the labor that made the clothes that built the art? How many of us were wearing denim in that building on that day?

Jamal Cyrus, “Blue Alluvial Glue (Line)," 2022, Denim, cotton thread, cotton batting, and metal, Overall: 42 1/2 × 55 inches. Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago.

Its sister piece, Blue Alluvial Glue (Line), hangs horizontally, rolling thick dark denim on a single curve, upper left side to right edge. A zipper near the top looks like a scar, and, being near the top, seems like a fundamental restructuring of our expectations for a zipper. These are simple details. But where art meets lived experience, anything that appears simple usually isn’t.

Jamal Cyrus, “Horn Beam Effigy," 2022, Saxophone, steel rail, railroad ties, dirt, denim, and wood, Overall: 76 × 84 × 84 inches. Courtesy the artist and Inman Gallery, Houston and Patron Gallery, Chicago

Horn Beam Effigy, a totemic scarecrow bird-god with a saxophone for a head, shares a room with the Blue Alluvial siblings. Its base is a raised garden pen filled with coarse clumps of dirt. The bell of the instrument, angled down to the pole, makes the mouth; the reedy body is now a proboscis. Bits of rope stand for hair and beard. Crudely cut wooden wings have a down of denim. Somehow, despite the cold crudity of its formation, Horn Beam Effigy radiates the presence of a warm, living being.

Music is all over this show. I sometimes felt I was in Chicago, and I can give no greater compliment than that to another city. In Transit, Accompanied by Double Bass and Saxophone is a looped sound installation in what, for me, was the last part of Cyrus’ show. Notes from sax and bass are mixed with machinery sounds and noises from trains. It’s so subtle that it sounds like it’s coming from another room, from the other side of a particular wall. I headed that way in search of the source, but was tricked. If you close your eyes, you’ll be standing outside of a blues club. I finally spotted an audio speaker visible in one ceiling corner, but was sorry I looked. In the end, I didn’t want to know.

If denim, as the artist volunteered in his interview with associate curator Alison Hearst, contains “a specific history but can be universal and operate more on an emotional level,” then his use of musical objects and sound spins the exhibition through an unexpected regional looking glass: Fort Worth, and what that city has given to Jazz. I knew Ornette Coleman was a Fort Worth native, but I was not familiar with Julius Hemphill. Like Coleman, Hemphill was an innovative force in the Free Jazz movement of the 20th century’s latter half. Coincidentally, as I studied up on Hemphill after seeing Cyrus’s show, I discovered this piece: “Hymn for Julius Hemphill” by Dennis Gonzalez, the beloved Dallas jazzman who died on March 15. It was another discovery, another riff on the theme that, in the end, we’re all connected.