Camera Austria International ISSU.160

Camera Austria International. / Jan 10, 2023 / by Lara Schoorl

Transcription below:

In the act of longing, time is suspended, possibly infinitely. Friction between the hope for joy and the pain of loss, dramatically balanced, keeps our heartbeat elevated. We are all familiar with this element of emotional risk. Set off, en route, but not yet there; an imaginary, unknown, but desired place. Longing, then, is an in-between; an abstract space, a lonely phantom space. Arguably a queer space; holding the possibility of something different, not new, where longing be- comes a transformational process. This process recurs threefold in Brittany Nelson’s exhibition Meet Me At Infinity.

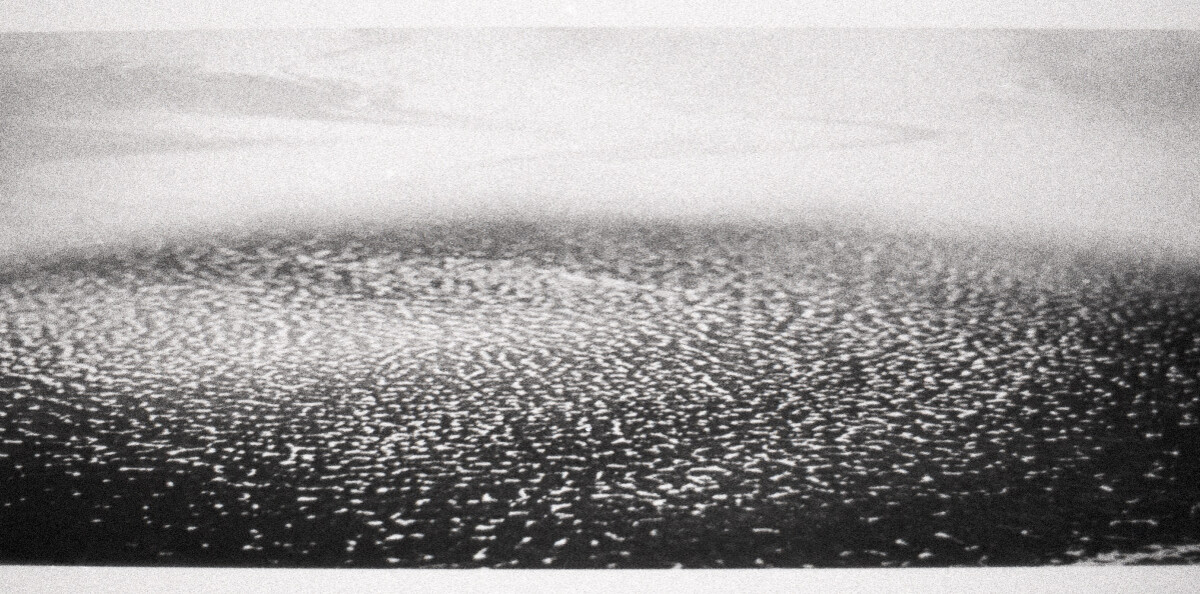

In the brightly lit main space of Oslo’s Foto galleriet, six large bromoil photographs––the largest bromoils ever made––depict Martian landscapes: rolling sand hills and rocks, a deserted surface but for a set of tracks hinting at the presence of a vehicle. The images were taken by the robotic rover Opportunity, and then reproduced by Nelson. In 2004, NASA sent two rovers, Opportunity and Spirit, to Mars with the instructions “to roam the planet for 90 sols (90 Martian days corresponding to 24 hours and 40 minutes each), collecting data on territory, evidence to provide clues on ancient life and water, and other findings that might brace hypotheses of future habitability,” as is stated on the artist’s website. Both robots survived long beyond their expected life cycle: Spirit ceased communication in 2011, while Opportunity continued to wander the red planet alone, taking photographs and sending them back to Earth, until June 10, 2018.

Although the initial NASA mission of the two rovers proposed a colonial longing for life else-where, the high-viewpoint images––suspended if you will––taken by Opportunity, which are on view in the exhibition instead show a romantic iconography. Looking back at its own solitary footsteps or carefully framed dunes, the view Opportunity shares presents a desire not for something new but rather for something re-imagined, something already there, be it a longing for its former partner, Spirit, or for keeping the landscape as is, absent of humans. We are not given a definite answer, but the focus on these tilted angles provides a space for thought experiments. Nelson subtly fuels this re-imagination of an existing perspective in both the conceptual and the technical underpinnings of her Opportunity (2019) series. She did not take these images; they were also already here (in NASA’s archives, available to anyone). Reproducing them at roughly 107 by 178 centimeters using the nineteenth-century bromoil process, Nelson further abstracts the already grainy landscapes. The bleached-out, dried, and inked-over photo- graphs, created in isolation of up to twelve hours, appear handled and fragile. They require some distance, in order to let the black border (around which a white space is left open till the edge of the paper) speak for the singularity of perspectives amid the chaos of a universe full of looking, searching, wanting, and of blowing sand.

In an adjacent room, smaller and dark, six letter-size works ask us to step closer, but not with- out warning. Backlit with red light, they imbue a hint of danger, installing just the right amount of doubt regarding our presence to spark curiosity. The works appear to be a series of glass-plate-reflective holograms that embody a selection of letters by James Tiptree Jr., titled Tiptree’s Dead Birds (2019). Tiptree is the male pen name for Alice B. Sheldon; and Sheldon wrote as Tiptree–– known for his science-fiction writing, a predominantly male field––to express herself freely in her closeted sexuality. These very personal letters, written as Tiptree to herself, detail her experiences with various women who rejected her throughout the years. The emotions in the letters echo around the room, and the red light evokes love, lust, anger, and, of course, longing. Not only does the installation of Tiptree’s Dead Birds, mirroring the number of works and contrasting the light and size, draw an immediate parallel with the Opportunity series on the other side of the wall; the evident solitude of Tiptree’s hidden gay life strikes comparison with the lonely rover on Mars. The suggestive holographic dimensions make us believe that these pages can be turned. Slightly tilted, one is but barely able to see the verso side. It is thus through illusion that Nelson shows only the marked surface, one side, one perspective.

Meet Me At Infinity is a reflection on longing. Longing as a romantic, queer, and abstract act that is used to carefully flip dominating narratives with the possibility of different ones–– none given, all open-ended. Skeptical of predetermined solutions and prescriptive narratives, Nelson homes in on the process of technique, of thought, of leaving muddy questions in. The exhibition ends, for now, if I may say so, with per- haps the most visceral symbol of longing in a single work. Visible only partially through a slit in the back wall of the gallery. Keeping us at a literal and imposed distance. Here, beyond reach, Nelson shares a fragmented picture of the “Face on Mars” shot by NASA’s Viking 1 spacecraft in 1976. Letting us see the image that embodies our anthropomorphic longing (the desire to see ourselves elsewhere in space) the artist thereby, through this exaggeration, again applies a small fissure in our perception of others, human and nonhuman. It is also the beginning of a new series of works by Nelson. It asks: What do you (want to) see?

Lara Schoorl is an independent writer based in New York (US). Her writing can be found in Flash Art (IT), Los Angeles Review of Books (US), Journal of Grievances (US/CO), DIG (NL), Autre (US), and more. She is also the editor-in-chief of Close Distance (US/NL).