Virtual Horizons: Gwangju

Hyundai Artlab / Jun 23, 2023 / by Hunter Braithwaite / Go to Original

Welcome back to Virtual Horizons, a look around the art world of today—and tomorrow. We started in Los Angeles for a deep dive into the city’s primeval (and technological) past, and then found art and transformation on the streets of New York. Now, we’re popping across the Pacific, flying 8,000 miles and 16 hours into the future, touching down in Gwangju. This summer it’s not just the city of light, as its name translates to. It’s also the city of water.

That’s due to the 14th Gwangju Biennale: soft and weak like water. The title comes from a line in Laozi’s Dao De Jing—a 2,500-year-old text that still resonates today. “There is nothing softer and weaker than water,” it goes, “…and yet there is nothing better for attacking hard and strong things.”

Artist Buhlebezwe Siwani performs as part of Confluences: Stories of Art and the Planetary symposium, organized by the Gwangju Biennale Foundation and Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational.; Photo: BAY STUDIO (Choi seongung)

As it meanders through the adjacent fields of poetry and politics, this liquid sentiment defines the curatorial framework under the vision of the artistic director of the 14th Gwangju Biennale, Sook-Kyung Lee. “An aqueous model of power that brings forth change…[through] pervasive gentleness.” It’s an apt metaphor—not only for works in this iteration—but for the evolution of the Gwangju Biennale itself.

Seldom does an art biennale embrace a history as harrowing as Gwangju’s. The city was the site of the 1980 pro-democratic uprising. To commemorate sacrifices at that time, and to celebrate the return to democracy, in 1995 the Biennale was founded in the dedicated Biennale Park near the university in the northeast of the city.

What has happened since looks to the “pervasive gentleness” quoted above. Over the course of nearly three decades, Gwangju’s global recognition has skyrocketed. Though less than a quarter of the size of Seoul, the city represents Korea’s place within the global arts conversation as much as any spot on the map. It is a model for a specific type of exhibition-making. And, more generally, it provides a masterplan for the civic power of art to approach history and define a place.

The inaugural edition, 1995’s Beyond the Borders, attracted 1.6 million people with its exploration of globalism through the lens of contemporary art. Since then, both show and city have become shorthand for biennales, its two syllables mentioned alongside Venice, and as such has secured top curatorial brass, including Defne Ayes, Okwui Enwezor, and Massimiliano Gioni. This year’s appointment of Sook-Kyung Lee marks the first time a Korean curator has led this international event alone since 2006.

More than that, it’s an incubator for the curatorial frameworks that continue to shift and expand the cartography of the contemporary art world. As part of the opening, the Gwangju Biennale Foundation and Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational hosted a two-day symposium titled Confluences: Stories of Art and the Planetary. Because that could also be the tagline for this column, we caught up with one of the co-convenors, the London-based curator Odessa Warren, who just arrived in Gwangju for the first time.

Sook-Kyung Lee, artistic director of the 14th Gwangju Biennale, introduces the Confluences: Stories of Art and the Planetary symposium.; Photo: BAY STUDIO (Choi seongung)

“I had heard that the Gwangju Biennale stood out amongst other biennials as a centre for artistic exchange,” says Warren, who is Assistant Curator, International Art, Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational at Tate Modern in London. “When I arrived, I felt that there was a real sense of that - many of the artists had been there for several weeks installing their work and there was what felt like an artistic community that had formed around the biennale.”

Warren reasons that the Biennale’s size and location contribute to this sense of intimacy in what is ostensibly an international art event. But so does its history. In preparation for her trip, she read about the 1980 Gwangju Uprising, and was “intrigued by what people call the ‘Gwangju Spirit.’ It was very interesting to visit a biennale which was inaugurated to commemorate such a strong political history…Indeed, the fact this internationally recognised art biennial is directly tied to the democratic uprising in Gwangju is quite unique and sets it apart, as it’s not often that a major artistic event has such an origin story.”

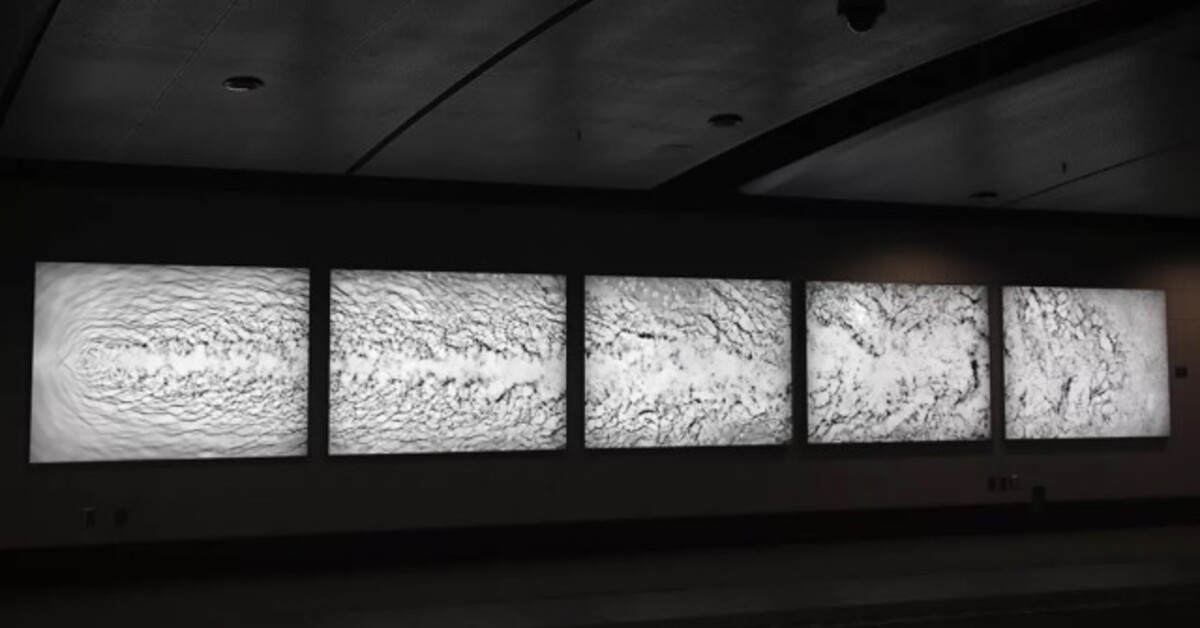

soft and weak like water showcases the work of 79 artists across five sites: the Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall—the main exhibition venue—and the Gwangju National Museum, Mugaksa, Artspace House, and Horanggasy Artpolygon. The works on display are wide-ranging and expansive, but Warren points out two new commissions that focus directly on the history of the city: “Both Pankgrop Sulap and Aliza Nisembaum’s works were both beautiful and moving. The former produced large banners which hung in the gallery space and depicted archival images from the democratic uprising made using a traditional woodcut printing technique. As for Nisembaum, her paintings were produced in collaboration with a local theatre group Shin-Myong in Gwangju and depicted scenes from a performance entitled Someday in Spring which tells the story of families who lost loved ones during the uprising.”

Pangrok Sulap, installation view of Gwangju Blooming, 2023. Woodcut print on blackout cotton. Dimensions variable. Commissioned by the 14th Gwangju Biennale.; Courtesy Pangrok Sulap and Gwangju Biennale Foundation. Photo: glimworkers.

If the tumultuous wellspring of the 1980 Uprising provided the occasion for the Biennale, and it still inspires artists today, the liquid nature of its implications through culture is charted over the course of the exhibition, as well as the Confluences symposium, which featured artists like Judy Watson and Hera Büyüktaşcıyan, included performances by Buhlebezwe Siwani and Noé Martínez. “The biennial proposed to think through the restorative potential of water as a metaphor, force, and method…[to] imagine our planet as a site of resistance, coexistence, solidarity and care,” Warren explains that “for the symposium, we decided to expand on these themes of and center artistic voices engaged in alternative models and practices that imagine other ways of knowing and living together.” The result was two days of conversations structured around notions of source, undercurrents, estuaries, and tributaries.

Artist Noé Martínez performs as part of Confluences: Stories of Art and the Planetary symposium, organized by the Gwangju Biennale Foundation and Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational.; Photo: BAY STUDIO (Choi seongung)

How art and thought originate, how they bubble up from the earth, and then spread through borders both natural and imposed, was the driving force of the conversation. “The talks touched on issues related to world-making and ecologies, contested spaces and memories, histories of colonialism and imperialism, plural epistemologies and cosmologies, as well as collaborative and community-engaged artistic practices.” Warren notes that while the Centre’s previous gatherings have zoomed in on a specific place or idea, this one tackled what was termed our “transnational entanglements.” It was a tailor-made conversation for the Centre, which works to recontextualize the Tate’s collection within new, global perspectives on art and history. This, for Warren, extends the mission at the heart of the curatorial practice. “As curators, part of our job is to translate and care for the stories that these artists and artworks are telling.”

Of the nearly 80 artists with projects in Gwangju, I asked Warren to give a brief rundown of her standouts. She pointed to Guadalupe Maravilla’s “Disease Throwers” as a striking example of an artist whose art is part of an expanded practice which is embedded directly in politically engaged community work, which he spoke about during the symposium. The Biennale has been a site of discovery for most of its visitors. Warren’s introduction to artists such as Chang Jia was paired with the joy of seeing works by artists she was already familiar with, such as Edgar Calel and Judy Watson. And then there was Meiro Koizumi’s commission Theatre of Life, where the artist staged a two-day workshop with teenagers from the Goryeo community to explore issues around identity, history and power. At the end though, for Warren and others, there was too much great work to list. Best then to see for yourself.

After Gwangju, Warren returned to London, where she co-curated a five-week program for Richard Bell’s Embassy in the Turbine Hall at Tate Modern. The tent is an homage to the 1972 Aboriginal Embassy protest and acts as a space for activism and dialogue in support of Indigenous land rights in Australia and beyond. It’s summer, and the year is speeding up, seemingly faster than the last. But if things seem panicked, the 14th Gwangju Biennale encourages us to take a step back. Given time, water—softness and weakness notwithstanding—can chisel through continents. We hold the same hopes for art. We are right to do so.

Hyundai Tate Research Centre: Transnational’s vision is to explore new perspectives on global art histories and highlight global exchanges between artists and their ideas. Established in January 2019 as part of a long-term partnership between Tate and Hyundai Motor, the Centre reflects a shared vision of how connections that have been overlooked can provide a new way of framing history.