First Impressions From the 2024 Whitney Biennial

Hyperallergic / Mar 14, 2024 / by Hrag Vartanian, Valentina Di Liscia and Natalie Haddad / Go to Original

Installation view of Isaac Julien, “Once Again … (Statues Never Die)” (2022) at the 2024 Whitney Biennial (photo Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

As the Whitney Museum’s signature event, the Biennial is a highly anticipated exhibition that often acts as a barometer of trends and ideas percolating in global art communities, as told through an American lens. It tells us a great deal about New York’s art community and its priorities, while highlighting emerging critical ideas that influence many artists and future exhibitions. One troubling trend that has continued from the last few Biennials is that the Whitney Museum has not allowed media questions during its press conference. (And the museum has historically offered limited access to its director — Hyperallergic has repeatedly been denied an interview with former Director Adam Weinberg, even as he officially claims to support controversial ideas and protests at conferences in autocratic countries.) This year, the institution doubled down on these undemocratic tendencies by canceling its press remarks, opting instead for an “open house” format for journalists under the guise of accommodating record number of RSVPs (which were not apparent at the moderately busy preview). A far more likely explanation is that museum personnel were scared of protest actions related to Gaza. It’s unfortunate that the Whitney Biennial’s organizers have not embraced the lightning-rod nature of an event that has made the museum relevant in the first place.

Below are our first impressions from the 2024 Whitney Biennial, Even Better Than the Real Thing. — Hrag Vartanian

Installation view of Suzanne Jackson’s works featuring “deepest ocean, what we do not know, we might see?” (2021) (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

Suzanne Jackson

My most thrilling discovery at the Biennial was the work of Suzanne Jackson, whose suspended, abstract “anti-canvases” encompass an entire gallery. In what I can only understand as a sleight of alchemy, Jackson eschews the constraints of traditional support, instead pouring layers of acrylic medium onto plastic sheets and letting them drape like the ersatz sails of a fantastical vessel. The most impressive of these is a 108-by-125-inch expanse of pigment impeccably titled “deepest ocean, what we do not know, we might see?” (2021), whose gossamer surface offers glimpses of silhouettes and passing movements in the space. I found myself wanting badly to hold the material in my hands, to feel its weight much like one might plumb the depths of a body of water. — Valentina Di Liscia

Installation view of Sharon Hayes, Ricerche: four (2024) (photo Natalie Haddad/Hyperallergic)

Sharon Hayes

For me, an immediate standout was Sharon Hayes’s two-channel video Ricerche: four (2024). Even without watching the full 80 minutes, the documentary — the last in a series of works addressing gender and sexuality — should be illuminating for any audience members, whether queer or straight. The artist establishes an almost familial tone as her interview subjects sit in a group and converse (a configuration echoed by the mismatched chairs set up around the monitors), yet the subject matter is anything but casual. A diverse group of queer and genderqueer people offer intimate observations on their fears, frustrations, and the disparity between the ideals and realities of life as an LGBTQ+ person — the discrimination that comes from without and within. Hayes avoids didacticism by making a space for individual stories. The videos can be hard to hear in a busy gallery, so subtitles would be helpful, as the work is worth a watch. — Natalie Haddad

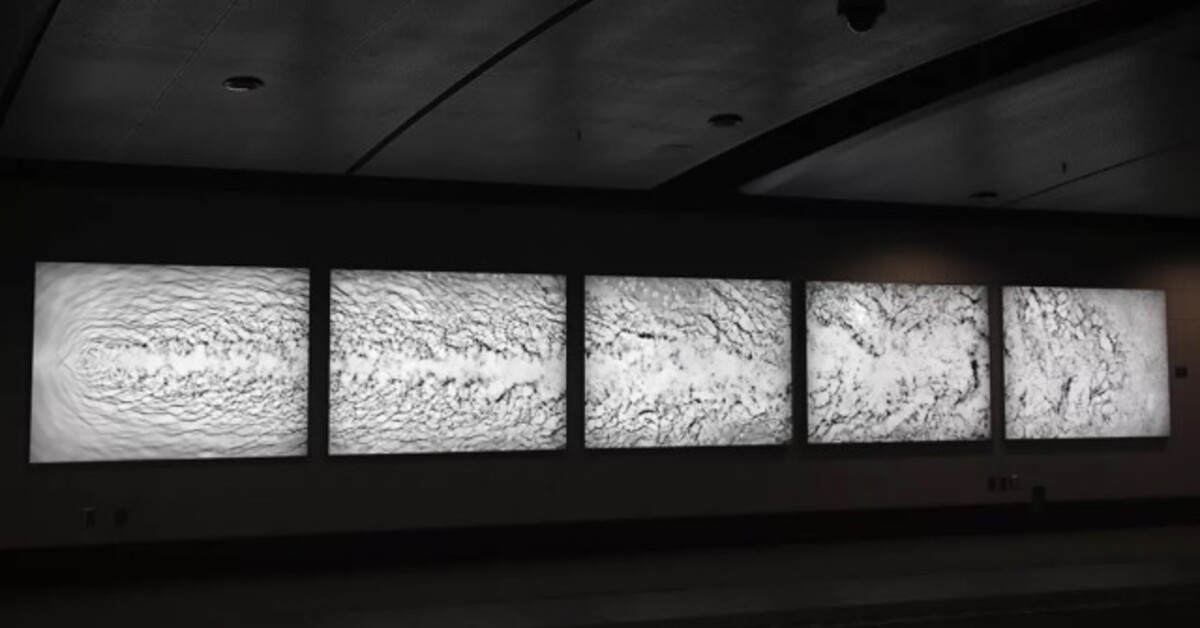

Installation view of Isaac Julien, “Once Again … (Statues Never Die)” (2022) (photo Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

Isaac Julien

This installation, which features multiple screens and five historical and contemporary artworks, encapsulates what the veteran queer British video artist does best: enabling us to linger and examine those moments of interpersonal desire and connection that are often overlooked in a field seemingly obsessed with objects. The videos are the stars of this presentation, as the objects feel obscured and pushed to the edges, perhaps to suggest that they are receding into the shadows to allow the voices of those who placed them there to shine. While the work focuses on the Pitts-River Museum in the United Kingdom and the Barnes Collection in Pennsylvania, the artist decided to use the interiors of the Pennsylvania Fine Arts Academy, as well as other spaces, as a stand-in for the original Barnes mansion-turned-museum. This was one of the best videos in a Biennial with some very strong video work. — HV

Installation view of the 2024 Whitney Biennial featuring Dala Nasser, “Adonis River” (2023) (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

Dala Nasser

On view on the fifth floor is a massive, sparse wooden structure draped in stained bed sheets that looks like someone attempted to build a Neoclassical fort and gave up less than halfway through. The fabrics have been rubbed with rocks from Mount Lebanon’s Adonis Cave and Temple, where the legendary mortal lover of Aphrodite was slain by a wild boar, and then tinted a rusty red using clay from the banks of the Abraham River — not that you would glean any of this by looking at the work. The multiplicity of references here is beautiful, entwining the mythical story with the Shia Muslim mourning rituals of Ashura, a day that commemorates the martyrdom of the Prophet Muhammad’s grandson. But these poetic throughlines of erasure and resurrection are lost in the material reality of the structure. A version of this work was shown at the Renaissance Society in Chicago last year, where (at least according to photos online) it was presented as a standalone installation in a brightly lit gallery whose Gothic architecture appeared to bring out its spiritual possibilities. At the Whitney, most of this is obscured, and we’re left with the vibes of an abandoned construction site. — VD

Penelope Spheeris, still from “I”I Don’t Know” (1970), 16mm film, black and white, sound; 20:11 minutes (© Spheeris Films Inc., courtesy the artist and Motion Picture Academy Archive/Avatar Films)

Penelope Spheeris

Long before I had heard of any other Biennial artist, I admired Penelope Spheeris. Though best known as the director of the 1990s Saturday Night Live movie Wayne’s World, I was a fan because of her documentary The Decline of Western Civilization Part II: The Metal Years. (Part one was about punk.) The 20-minute “I Don’t Know” from 1972 may seem out of left field, but the story, both scripted and improvised, about the relationship between a cis lesbian and a trans person who was nonbinary before the term existed foreshadows a career spent with people of all different walks of life, shining a light on them with respect and infectious interest. — NH

Installation view of four paintings by Harmony Hammond: “Patched” (2022, not in photo), “Black Cross II” (2020–21), Chenille #11 (2020–21), and “Double Bandaged Quilt #3 (Vertical)” (2020) (photo Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

Harmony Hammond

This austere black-and-white painting incorporates the history of modernism, seemingly quoting Kazimir Malevich’s “Black Cross” (1915), Frank Stella’s geometric work of the 1960s, and others to address the violence against women as a result of abortion prohibitions or sexual assault, and how this violence can be weaponized against women. Hammond relies on patterns and repetition to suggest a new perspective, while evoking sewing or quilting, which historically have been characterized as feminine. However the artist refuses to make these objects delicate or subtle, giving us instead a brash statement of power in the face of the helplessness that the news of the last few years has engendered in many of us. — HV

Karyn Olivier, “How Many Ways Can You Disappear” (2021), potwarp; lobster traps; buoys washed ashore on Matinicus Island, Maine; and rope reproduced in salt, 179 x 98 x 73 inches (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

Karyn Olivier

I am not itching to negatively review any artwork that attempts to address something as serious and urgent as migratory disaster and displacement, especially in a Biennial with so few references to global crises. And Trinidad-born Olivier, whose oeuvre includes thought-provoking works reimagining the oppressive logic of monuments, knows a thing or two about engaging audiences with public art. But this heap of tangled ropes, buoys, and other ocean detritus conjures little more than the all-too-general idea of something washed up on the shore; a more specific picture never comes into relief. The most successful aspect of the installation is the dangling rope, which the artist has cast in salt in a reference to the practice of bartering salt in exchange for enslaved people in Ancient Greece, but it’s easy to miss this detail given the vagueness of the rest. — VD

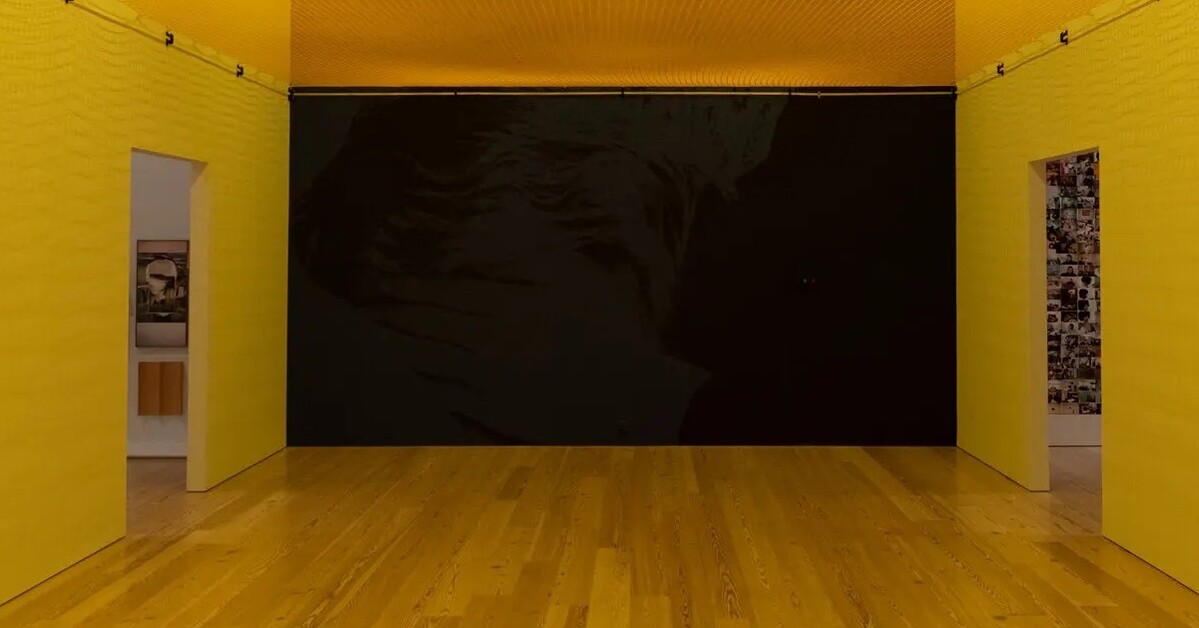

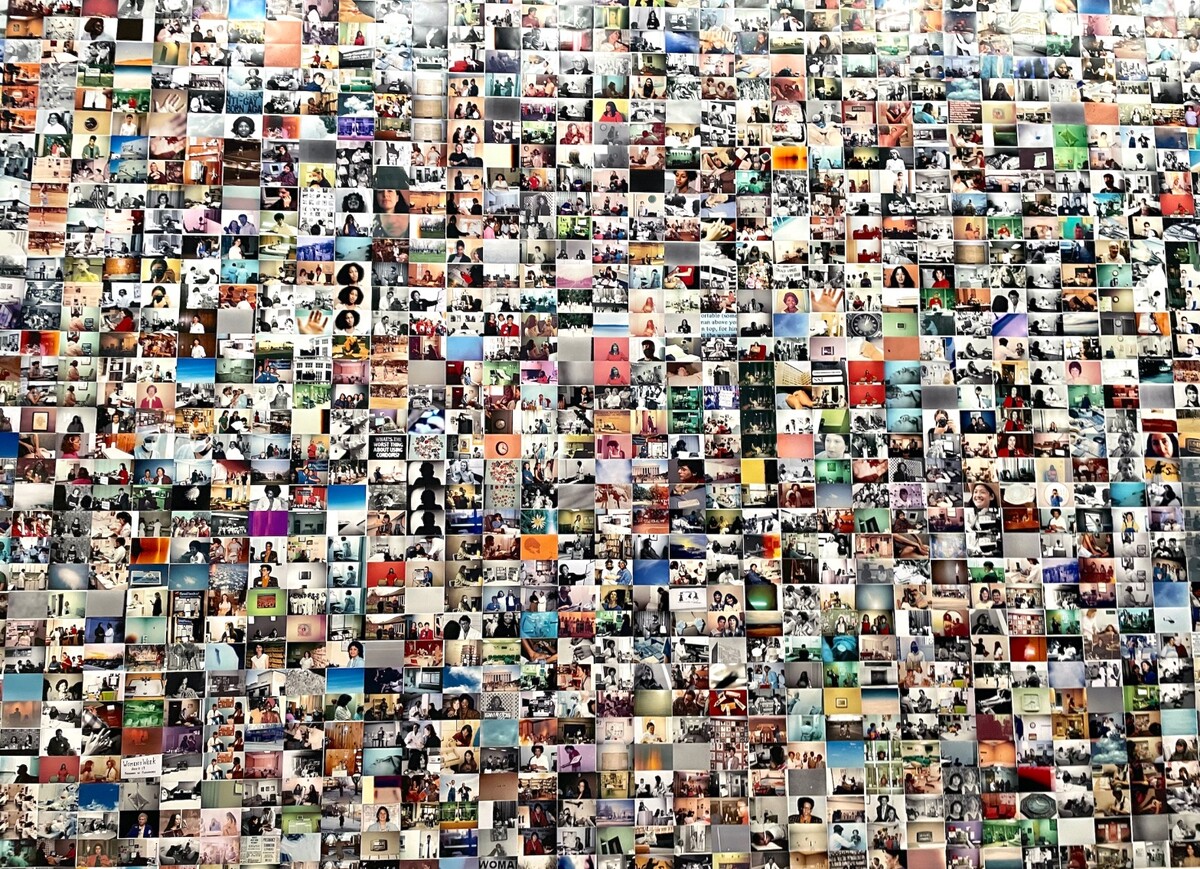

Carmen Winant, detail of “The last safe abortion” (2023), inkjet prints (photo Natalie Haddad/Hyperallergic)

Carmen Winant

Carmen Winant’s work struck me as a case study in how politics can be meaningful and impactful in a museum. “The last safe abortion” is a monumental collage of over 2700 photographs recording day-to-day activity at health and abortion clinics and protests following the overturning of Roe v. Wade. Most visitors likely will agree with Winant’s clear feminist and pro-choice politics, so it’s not really about changing minds. What the work can do is transform what is an abstract issue for some into a tangible ordeal encompassing emotional and physical stress, time, money, logistics, and the efforts of many, amid life’s other stresses. Abortion access is a right, yes, but Winant’s subjects reiterate that it’s a lived experience too. — NH

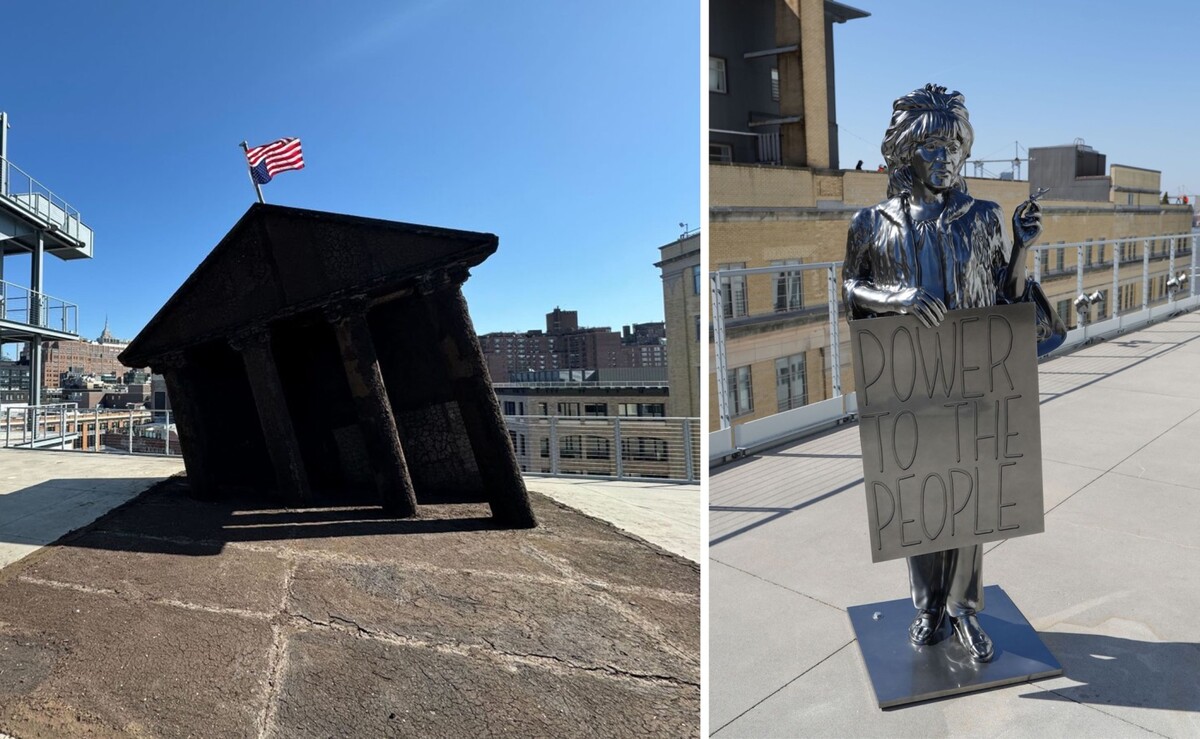

Kiyan Williams, “Ruins of Empire II or The Earth Swallows the Master’s House” (2024) and “Statue of Freedom (Marsha P. Johnson)” (2024) (photo Hrag Vartanian/Hyperallergic)

Kiyan Williams

These two obvious one-liners fall mostly flat, and I can’t stop thinking about how much Williams’s statue of Marsha P. Johnson looks like Rob Priutt’s Andy Warhol sculpture, “The Andy Monument” (2011). While it’s wonderful to recognize Johnson’s incredible contributions to the LGBTQ+ movement, and she is the subject of two artworks at this year’s Biennial, I find myself wanting to move away from celebrating a single person and, rather, to uplift the many Black trans, queer, and other LGBTQ+ and Black histories in the last few decades — these movements are built with many hands, and by continuing the iconographic practice we inevitably reinforce the importance of singular individuals in enabling change. — HV

Installation view of Carolyn Lazard, “Toilette” (2024) (photo Valentina Di Liscia/Hyperallergic)

Carolyn Lazard

My love for this ladder-like floor piece constructed of mirrored medicine cabinets was only made stronger by the realization — thanks to my overhearing a curatorial assistant’s conversation in passing — that the storage sections of the structures are filled with Vaseline. The surfaces take on a yellowish hue that is at once sickly and sleek, a perfect representation of the many tensions and contradictions of having and managing a human body. Lazard’s work is informed by their personal experience of chronic illness and imbued with a sense of endlessness and the labyrinthine.

PS. There’s no need to situate this in a Minimalist lineage, or whatever, in order to experience it fully. This Biennial, let’s normalize not name-dropping Donald Judd. — VD

Maja Ruznic, “The Past Awaiting the Future/Arrival of Drummers” (2023), oil on linen (photo Natalie Haddad/Hyperallergic)

Maja Ruznic

Paintings were surprisingly numerous at this year’s Biennial, but only a few commanded my attention. My favorites were two massive oil-on-linen works by Maja Ruznic. Although inspired by childhood memories of living in an Austrian refugee camp after fleeing her home in Bosnia during the Bosnian War, the colorful, dreamlike imagery evokes many barely remembered memories and pasts. In particular, the tall, totemic figures fading in and out of definition in “The Past Awaiting the Future/Arrival of Drummers” (2023) suffuse carnivalesque colors and patterns with an air of solemnity that recalls Max Beckmann’s strange, foreboding “Fastnacht” (“Carnival”) paintings and prints. — NH

Ser Serpas

It looks like installations by Edward and Nancy Kienholz and David Hammons had an offspring who ended up taking Ozempic. Undercooked, aesthetically underwhelming, this is a miss from an artist I normally find far more interesting. And what’s with the pretentious title? — HV

Diane Severin Nguyen

Step into a lusciously curtained room drenched in fuchsia light on the sixth floor and you’ll find plush, comfy bedding where you can plop down and watch Severin Nguyen’s entrancing 67-minute video. The piece portrays Iris, an actress rehearsing for a role in a film about the 1937 massacre of Chinese civilians in Nanjing, and is shot largely in the Hengdian World Studios in Zhejiang Province — the massive film studio whose productions have been criticized for sanitizing China’s history. I love it when videos are presented in thoughtful settings that activate and enhance the works, and experiencing “In Her Time (Iris’s Version)” in this uncanny pink universe immersed me in its subject matter in a more profound way than a more conventional display would. — VD