Abstract Language: A Review of Caroline Kent at the MCA

Newcity Art / Sep 13, 2021 / by Chris Miller / Go to Original

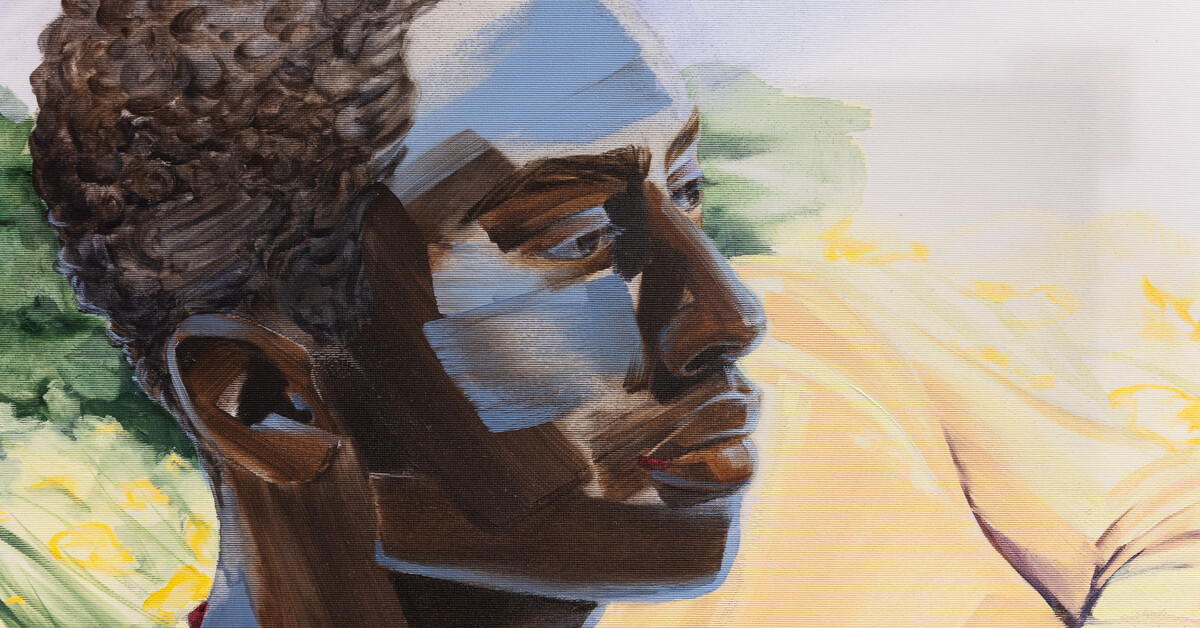

Installation view, “Chicago Works: Caroline Kent,” MCA Chicago Aug 3, 2021–Apr 3, 2022.

Picture a neo-Egyptian decor that’s more about West African spirituality than West European ideology. If you ignore

gallery signage, these two interior spaces at the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, designed for reading or writing, might well be showrooms for high-end home furnishings over at the Merchandise Mart. Every piece, and even the walls behind them, has been tastefully designed and expertly crafted. More than that, the style is a fresh and exciting variation on that Egyptian Revival decor that permeated Art Deco about a hundred years ago. But where early twentieth century decorators quoted ancient Egyptian motifs, Caroline Kent has imagined her own hieroglyphs and mythological figures—and they are no less fluid, elegant and timeless than the work done for Pharaoh Akhenaten’s fabulous new city of Amarna as shown in Chicago more than twenty years ago.

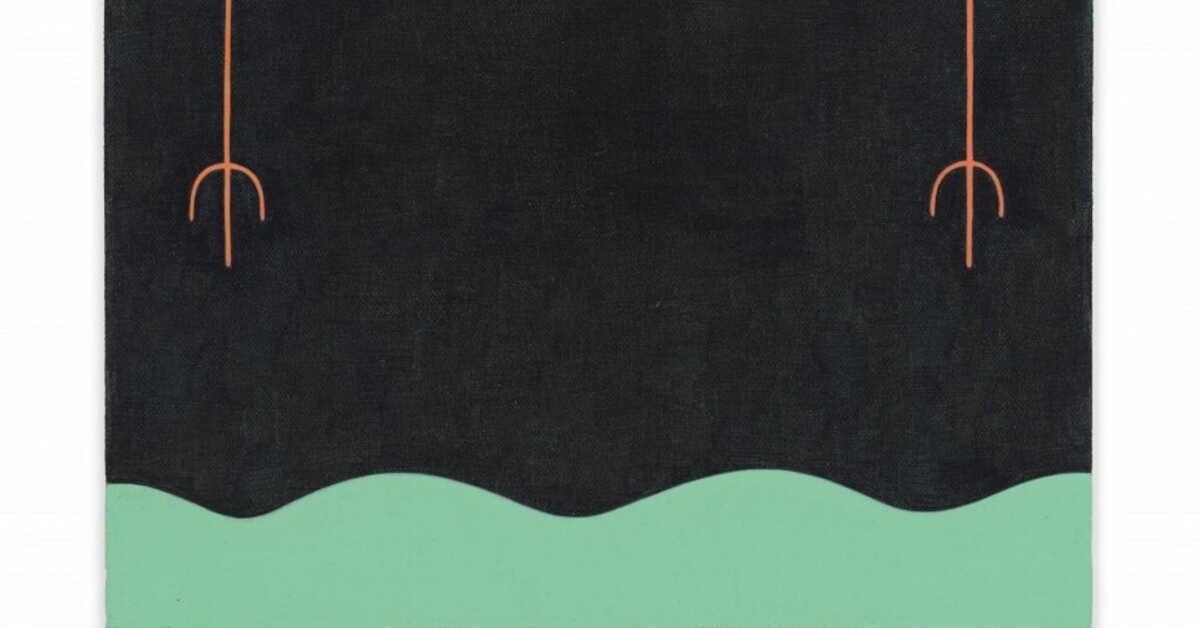

The large paintings are built around figurative gestures, yet still feel more like abstract paintings than narrative cartoons.

The gestures are as open, flowing, generous and regal as one might expect from benign, supernatural beings. The painting technique is the very opposite of hectic improvisation. Large, solid, simple shapes have been arranged with great care and their hard edges and surface textures executed with perfection.

The same could be also said about the wooden furniture, except that the level of craftsmanship is even more evident as

the design has incorporated the sometimes flamboyant grain of the wood. Of special note is the subtle inlaid marquetry on the writing desk. (I call it subtle because I did not notice it until the third viewing.) Two ghostly hands appear to emerge from the surface to pull open the small drawers at either end. It’s magical. Local multimedia artist Nate Young is credited as a collaborator on that piece, and I suspect he also executed the Brancusi-like wooden pedestals (or high African stools) as well, probably based on Kent’s rough sketches. As with the best furniture from pre-industrial times, the design and execution are inseparable.

Installation view, “Chicago Works: Caroline Kent,” MCA Chicago

These pieces are accompanied by explanatory statements posted in each room. Signage in the reading room connects the work to political questions in linguistics that have dominated the academic humanities for half a century: “How does language structure our world? Who gets to be inside or outside a language?” Signage in the writing room, however, tells us that “the exhibition explores the intimate correspondence between two identical twins who communicate telepathically,” where no actual language is required and power relationships could not possibly apply.

The signage does not address an African ethnic identity at all, which is rather remarkable given its trending status in the art world. Its obvious presence, however, feels all the more profound for being unspoken. The contradictory signs leave open to interpretation either a spiritual opportunity or a cause for political grievance.

I suspect that the “nuanced investigation of the relationship between abstraction, language, and translation” was just a respectful nod to the Euro-American cultural institution in which the exhibition takes place. What’s far more compelling is that special relationship between identical twins. It has been addressed by cultures all over the world, but has been especially important in West Africa where the green, wavy armed divine twins, the Nummo of the Dogon people, are progenitors less binary, and less guilty, than the Abrahamic Adam and Eve. They could possibly be represented by the tubular figures in Kent’s large paintings. The ambiance of her rooms also feels closer to Africa than anywhere else, and it has been established by more than just the West African snake plants whose broadcast of low frequency white noise makes them ever present. This is the Afrocentric legacy as a cause for joyful celebration, not anger or despair. And just as every American can be blissfully Irish on St. Patrick’s Day, we can all feel beautifully Black within this exhibition.