Curator Pablo José Ramírez: ‘Art history doesn’t belong exclusively to the western world’

Financial Times / Oct 4, 2024 / by Jonathan Griffin / Go to Original

When curator Pablo José Ramírez was asked to take charge of a section at the Frieze London art fair dedicated each year to special presentations, he wanted to shine a light on Indigenous and diaspora artists from the Americas, while acknowledging the unfixed and ambiguous identities these artists often inhabit. He titled it Smoke, inspired by “El Animal de Humo” (“The Smoke Animal”), a short story by Humberto Ak’abal, a Kʼicheʼ Maya poet from Guatemala, which describes a phantasmagoric creature that lives in the forest, part bogeyman, part guardian of the trees.

In Smoke, 11 artists, some of whom have Indigenous American heritage and others of whom are of mestizo (mixed) ancestry, show work in a variety of media, but predominantly clay. In Ramírez’s project, smoke is a metaphor, but it is also a byproduct of the fire needed to turn soft clay into hard ceramic.

“It’s not a section about Indigenous ceramics or Indigenous artists,” cautions Ramírez. The Guatemala-born curator, who was the inaugural adjunct curator of First Nations and Indigenous art at Tate Modern in London, before relocating to take up a curatorial role at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, refuses to let his work be pigeonholed. The artists he has chosen “move between worlds”, he says, between local traditions and the globalised contemporary art sphere. He aspires for the project to be inclusive, acknowledging how emigration disperses cultural knowledge across diasporas.

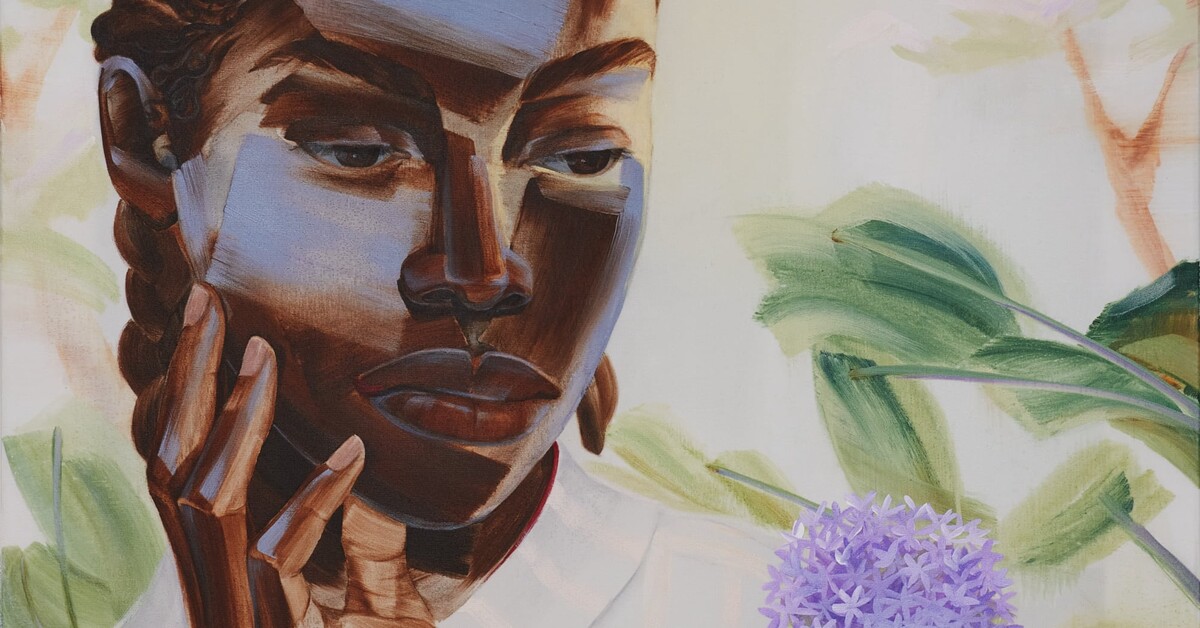

Indigenous Mexican artist Noé Martínez says that his sculptural ceramics are a means of communicating with his ancestors, the Huastec people. “They are containers to store the souls of my ancestors, slaves who were extracted in the 16th century,” he says. “The dead never leave, they are always in our daily lives.” As with many Indigenous communities, many of the Huastec people are now in diaspora. While his grandmothers worked with clay, their knowledge has been lost. “I use different materials than my ancestors, but I use them with the same thinking about the world that they had.”

The backgrounds of artists in Smoke are diverse. Christine Howard Sandoval was born in California and is an enrolled member of the Chalon Nation but now lives in Canada. Mexican-American Linda Vallejo, who was born in LA but moved around Europe as a child, was later invited to participate in Native American ceremonies through her involvement with traditional Mexican dance. (Both artists are represented at Frieze by Parrasch Heijnen.)

Vallejo’s sculptures at Frieze, made from found hunks of wood, paper pulp and other media, include no clay but — through their colours and materiality — allude to fire. As she explains, according to many Indigenous beliefs, “the fire lives within the wood”. Sandoval’s more conceptual works explore an Indigenous relationship to the land: a single Ohlone word (the traditional language of the Chalon people) is embossed on white paper, accompanied by a thick daub of adobe mud.

Not all the artists in Smoke claim Indigenous heritage, however. LA-based Roksana Pirouzmand was born in Iran. On the clay tablets she will present in Smoke, she paints bodies melding with mountainous landscapes, emphasising through her choice of medium the physical connection between a person and the land that claims them. Clay, for Pirouzmand, is a participant in her work: “I see the slow erosion that can occur between unfired clay and water as a performance of material,” she says.

Active, too, are works by the Brazilian artist Ayla Tavares. She places ceramic “totems”, as she calls them, in tanks filled with water. Tavares does not draw specifically on ceramic craft traditions, but instead references natural forms such as corals and anemones, fossils or slow-moving tectonic plates.

What binds this disparate group of artists is an understanding of land not in the nationalist sense but as terrain, as earth. (The soil on either side of any geopolitical border is, after all, the same.) For Ramírez this is a way of displaying work from distinct places, generations and traditions “with a certain degree of horizontality”, as he puts it. He sees a shift in the way that museums are framing craft-based, Indigenous and non-western artistic practices: “Institutions are finally trying to come to terms with the fact that art history doesn’t belong exclusively to the western world.”

His approach, as he demonstrates in Smoke, is to highlight connections while still acknowledging specificity, to question simplified models of identity and foster a climate of respect for difference.

In Smoke, 11 artists, some of whom have Indigenous American heritage and others of whom are of mestizo (mixed) ancestry, show work in a variety of media, but predominantly clay. In Ramírez’s project, smoke is a metaphor, but it is also a byproduct of the fire needed to turn soft clay into hard ceramic.

“It’s not a section about Indigenous ceramics or Indigenous artists,” cautions Ramírez. The Guatemala-born curator, who was the inaugural adjunct curator of First Nations and Indigenous art at Tate Modern in London, before relocating to take up a curatorial role at the Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, refuses to let his work be pigeonholed. The artists he has chosen “move between worlds”, he says, between local traditions and the globalised contemporary art sphere. He aspires for the project to be inclusive, acknowledging how emigration disperses cultural knowledge across diasporas.

Detail of ‘Racimo 3’ (2022) by Mexican Huastec artist Noé Martínez © Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery

Indigenous Mexican artist Noé Martínez says that his sculptural ceramics are a means of communicating with his ancestors, the Huastec people. “They are containers to store the souls of my ancestors, slaves who were extracted in the 16th century,” he says. “The dead never leave, they are always in our daily lives.” As with many Indigenous communities, many of the Huastec people are now in diaspora. While his grandmothers worked with clay, their knowledge has been lost. “I use different materials than my ancestors, but I use them with the same thinking about the world that they had.”

The backgrounds of artists in Smoke are diverse. Christine Howard Sandoval was born in California and is an enrolled member of the Chalon Nation but now lives in Canada. Mexican-American Linda Vallejo, who was born in LA but moved around Europe as a child, was later invited to participate in Native American ceremonies through her involvement with traditional Mexican dance. (Both artists are represented at Frieze by Parrasch Heijnen.)

Vallejo’s sculptures at Frieze, made from found hunks of wood, paper pulp and other media, include no clay but — through their colours and materiality — allude to fire. As she explains, according to many Indigenous beliefs, “the fire lives within the wood”. Sandoval’s more conceptual works explore an Indigenous relationship to the land: a single Ohlone word (the traditional language of the Chalon people) is embossed on white paper, accompanied by a thick daub of adobe mud.

Not all the artists in Smoke claim Indigenous heritage, however. LA-based Roksana Pirouzmand was born in Iran. On the clay tablets she will present in Smoke, she paints bodies melding with mountainous landscapes, emphasising through her choice of medium the physical connection between a person and the land that claims them. Clay, for Pirouzmand, is a participant in her work: “I see the slow erosion that can occur between unfired clay and water as a performance of material,” she says.

Active, too, are works by the Brazilian artist Ayla Tavares. She places ceramic “totems”, as she calls them, in tanks filled with water. Tavares does not draw specifically on ceramic craft traditions, but instead references natural forms such as corals and anemones, fossils or slow-moving tectonic plates.

What binds this disparate group of artists is an understanding of land not in the nationalist sense but as terrain, as earth. (The soil on either side of any geopolitical border is, after all, the same.) For Ramírez this is a way of displaying work from distinct places, generations and traditions “with a certain degree of horizontality”, as he puts it. He sees a shift in the way that museums are framing craft-based, Indigenous and non-western artistic practices: “Institutions are finally trying to come to terms with the fact that art history doesn’t belong exclusively to the western world.”

His approach, as he demonstrates in Smoke, is to highlight connections while still acknowledging specificity, to question simplified models of identity and foster a climate of respect for difference.