Charisse Pearlina Weston: A Drama of Materials

Mousse Magazine / Oct 7, 2024 / by Pujan Karambeigi / Go to Original

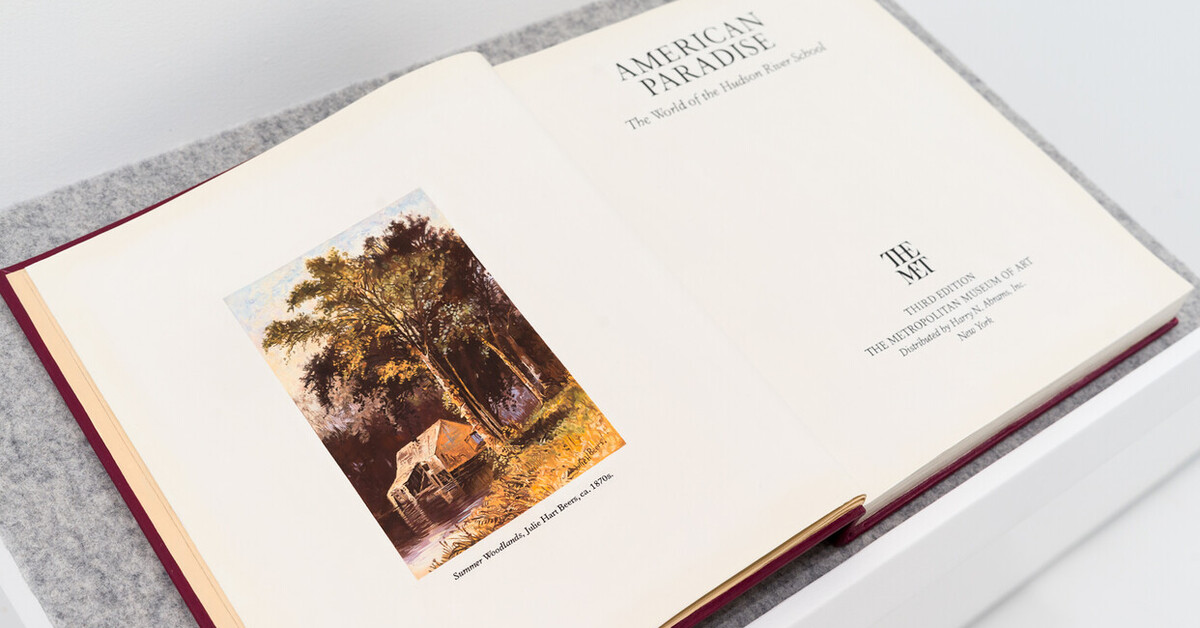

Charisse Pearlina Weston, and rust flows down, glistening (…to neon, to rolled sleeves, to arms, to pause) (detail), 2022. Courtesy: the artist; PATRON Gallery, Chicago; Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. Photo: Hai Zhang

In Charisse Pearlina Weston’s art, Baroque aesthetics make a comeback. But her work replaces the seventeenth-century preference for marble with glass, lead, and concrete, resulting in a drama of materials presented in three acts: order gives way to dynamism; substance is replaced by appearance; and, finally, the sculpture embodies an anguish of the soul.

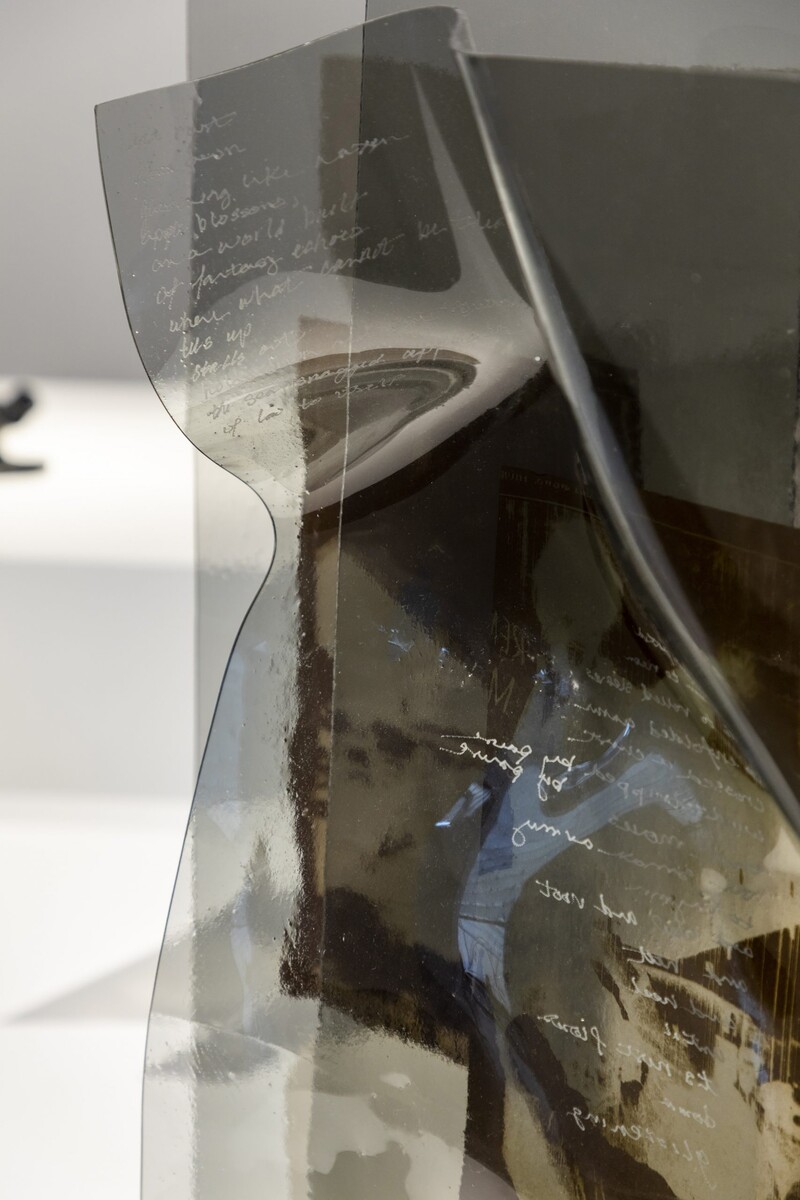

Weston’s of an intimacy who leaps and whirls within the warring of itself (2023), included in the Studio Museum’s artists-in-residence group exhibition And ever an edge at MoMA PS1, New York (2023), consists of a fused pane of glass stuck into a bent sheet of lead. Drama results from materials shaped in a way that amplifies tensions: glass versus lead, precarity versus durability, transparency versus opacity, slumped versus bent, verticality versus horizontality, standing up versus lying down, figure versus base. Weston purposefully creates a seemingly endless list of tensions, substantiating conflicts rather than dissolving them. This is not simply to expose the process of making, but to enlist these tensions in creating the illusion of movement, in articulating a pathos of spatial dynamism. Everything is, but could also be otherwise.

Weston, Texas-born and Brooklyn-based, received her MFA from the University of California at Irvine in 2019, followed by the Whitney Independent Study Program and fellowships at Princeton University’s Lewis Center for the Arts and elsewhere. Her creative process usually begins with rough drawings, followed by folding or slumping glass planes, or forming them in custom-made molds (usually executed at UrbanGlass in Brooklyn), with the final results often deviating more or less drastically from the initial drawing. In the aforementioned piece presented at MoMA PS1, the base is made of lead and bent in response to the shape of the glass. In more recent works, Weston also has fabricated her pedestals, with the ambition to create a sense of continuity between the disparate sculptural elements.

Sometimes the glass is etched, fired, or fused with archival prints taken from popular culture or protests (one example being the 1965 Watts Rebellion) that Weston finds while sifting through online databases or institutional collections. The actual content of these prints, however, is largely subsumed, their imagery rendered illegible through their exposure to the kiln. Indeed, the only person who can identify the print is usually the artist, who may or may not extend her knowledge to the gallerist, curator, critic, or collector. Likewise, her acutely poetic titles might carry references but remain cloaked in their idiosyncrasy; they are there for the artist to grip to, rather than for her audience to grasp. Weston’s sculptures, one could say, reference history as a general idea: it is there, but not to be consumed. The sculptures do not aim to uncover historical truths—at least, not to the viewer.

So how are we supposed to grasp Weston’s work? Or, how is it grasping us? Consider yolanda (2023), a work in her canvas series in which Weston creates the illusion of depth through layering and texturing, a play with opacity and transparency. An inkjet print on a canvas is scratched with glass shards from a pane that broke by accident, she tells me during a recent studio visit; the scribble interrupts the print’s straight lines and triangular shapes, with differently colored frit added to emphasize texture. Reductive and additive procedures transfigure the flat canvas into a deep space.

In an editorial introduction Weston wrote in 2018 during her stint as editor in chief of HAUNT, a graduate-student-run journal produced out of the Department of Art at UC Irvine, she called for using poetry to create nonlinear narratives and “embrace the discomfort from which we’ve been trained to pull away.” Discomfort, then, but of a kind that remains invested in contemplation. Not the discomfort of pathologizing the viewer’s perception, of telling them that their life is a lie. In fact, perceiving irresolvable tensions in her sculptures is true, not false, just as the depth in Weston’s canvases is not an optical illusion, but materially real. The tactility of the frit’s texture and the imagining of the sound of the glass scratching against the concrete base are not here to subvert the reality of the visual, but to bolster it. Weston’s work captures the discomfort of looking into a cloudless sky, realizing that infinity exists as both a potentiality and an abyss.

In Baroque aesthetics, this pathos of infinity had an ambiguous function. Art historians, mostly preferring Renaissance order over Baroque theatricality, understood it as a symptom of decadence, an aesthetic reflex of an impending societal collapse. For others, it represented “that anguish in the depths of the soul, that conquest of the imaginary world as a substitute for control of the real world,” as Fernand Braudel recounts in his anti–art historical art history Out of Italy: 1450–1650 (1991). That is to say, the Baroque contends with the simultaneity of being pulled up or pushed down—Heaven or Hell—never quite knowing which direction the journey will take.

The danger of being pushed down is most acute in the way Weston handles gravity. In her sculptures, the threat of collapse ensures the precarity of the glass (will it hold?) and thus maintains the Baroque harmony of forces. of [a] tomorrow: lighter than air, stronger than whiskey, cheaper than dust (2022) dramatizes gravity to transfer physical discomfort onto the viewer. The sculpture consists of six panels of tempered glass arranged in a grid and hanging from the ceiling at a slight tilt, overall measuring twenty by fifteen feet. When installed at the Queens Museum in New York for Weston’s eponymous 2022 institutional solo debut, it obstructed the passage between the two galleries featuring her work. This was the first time her sculpture forged a genuine architectural experience. The neat outlines of a pedestal were dispensed with in favor of an all-encompassing environment where the space of the work and the space of viewing mingled.

As an architectural intervention, the work’s immaculate grid and tidy angularity exert a different kind of compositional tension than the ones animating Weston’s stand-alone sculptures. The drama lies less in testing perception by having materials rub off against each other, and more in establishing an antagonism between work and viewer, with the looming threat of the glass ceiling positioning us in the here and now. The instructions are explicit: walk around, duck down if you dare, do not contemplate. No more losing yourself in the sheer infinity of tensions playing out in front of your eyes. No more pretensions of pulling you up. The direction of the journey is clear now.