‘Makeshift Memorials’ Solemnly Chronicles Art of the Pandemic Era

KQED / Oct 22, 2024 / by Quintessa Matranga / Go to Original

Looking back at the past four years is not necessarily something I’m ready to do, and yet it’s exactly what the latest exhibition at KADIST demands. For Makeshift Memorials, Small Revolutions, curators Lindsay Albert, Joseph del Pesco and Jo-ey Tang have attempted to collate artistic responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and the cultural shifts it brought into focus.

Good art is often celebrated for its timelessness, but this exhibition turns that idea on its head. Here we are tasked with time traveling back to the very recent past. A bowl of individually wrapped KN-95 masks on the front desk of the gallery helps usher in that transition.

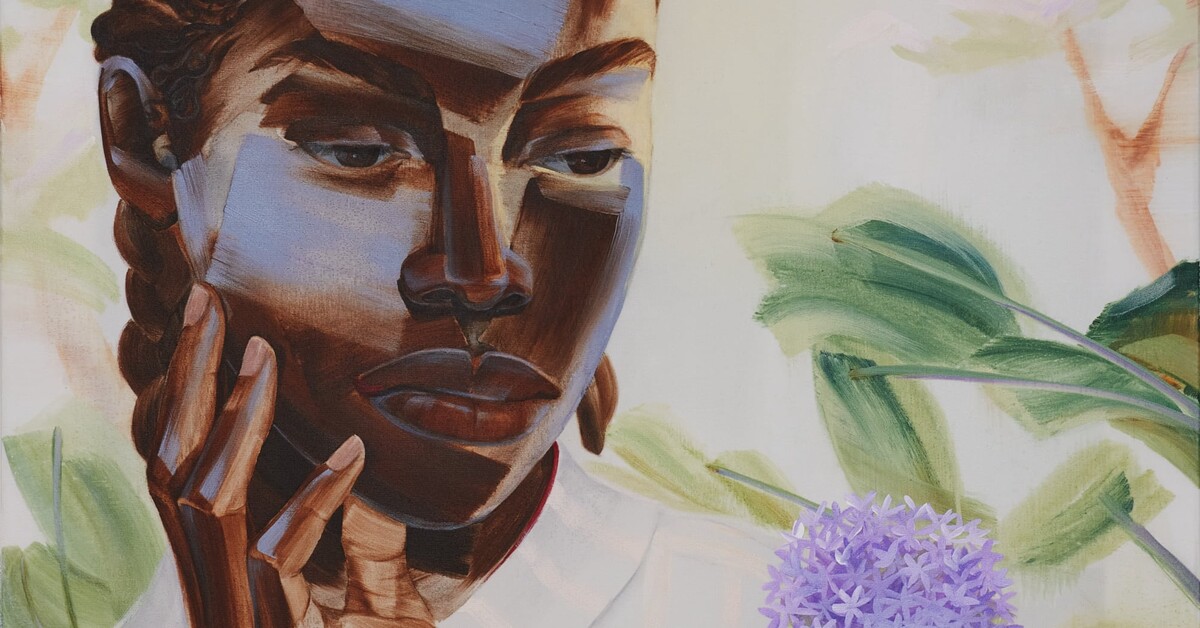

Makeshift Memorials is purposefully positioned against the impending U.S. presidential election, and the larger social context we are living through. In order to meet the moment effectively, the work (selected from the KADIST collection) must both represent our time and add to the continuum of art history. This is a tall order for any show. Here, visually and emotionally demanding paintings, videos, sculptures, photos, weavings and drawings hang side by side — competing for space and attention.

Moyra Davey, ‘Visitor,’ 2022. (Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection; Photo by Phillip Maisel)

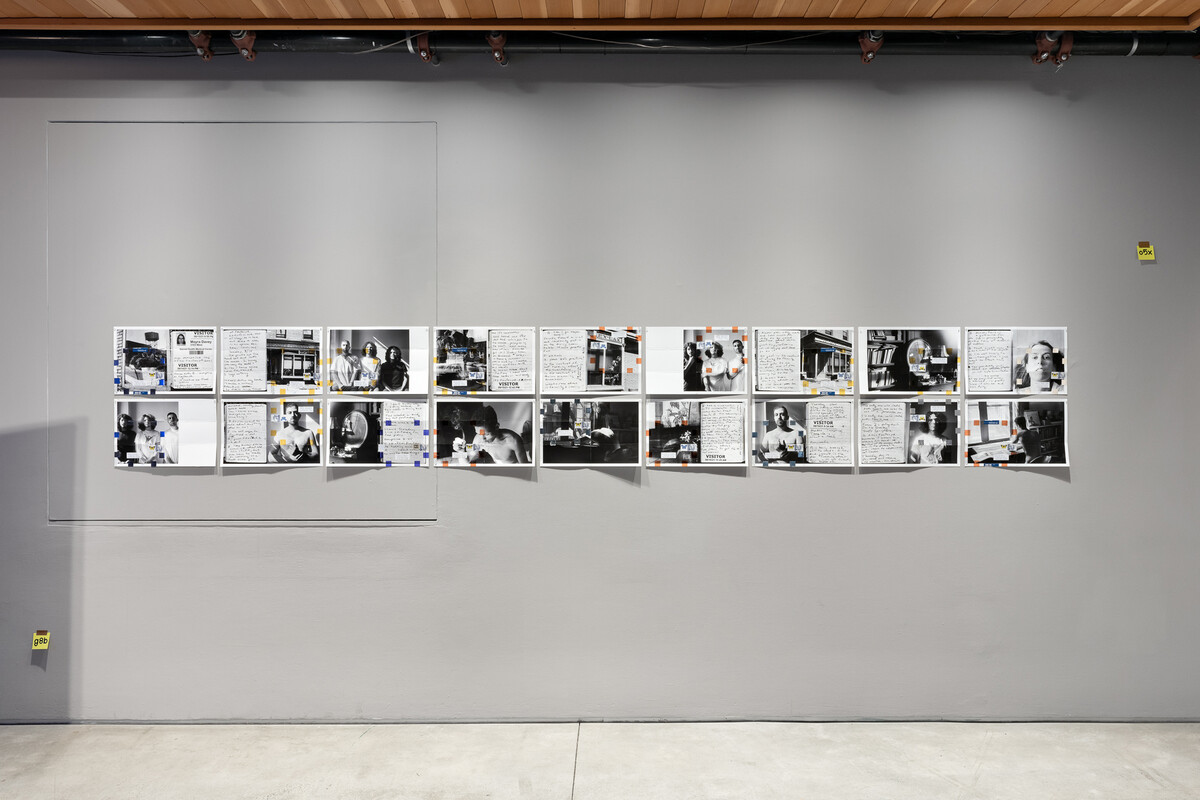

Upon entering the gallery visitors are confronted with an unconventional and slightly disruptive exhibition design. Highlighter-yellow sheets of A4 paper hang from the ceiling off wooden sticks, secured with torn pieces of brown packing tape. Caption details for the artworks on display are printed in bold black letters. Above each caption is an undecodable indexing system.

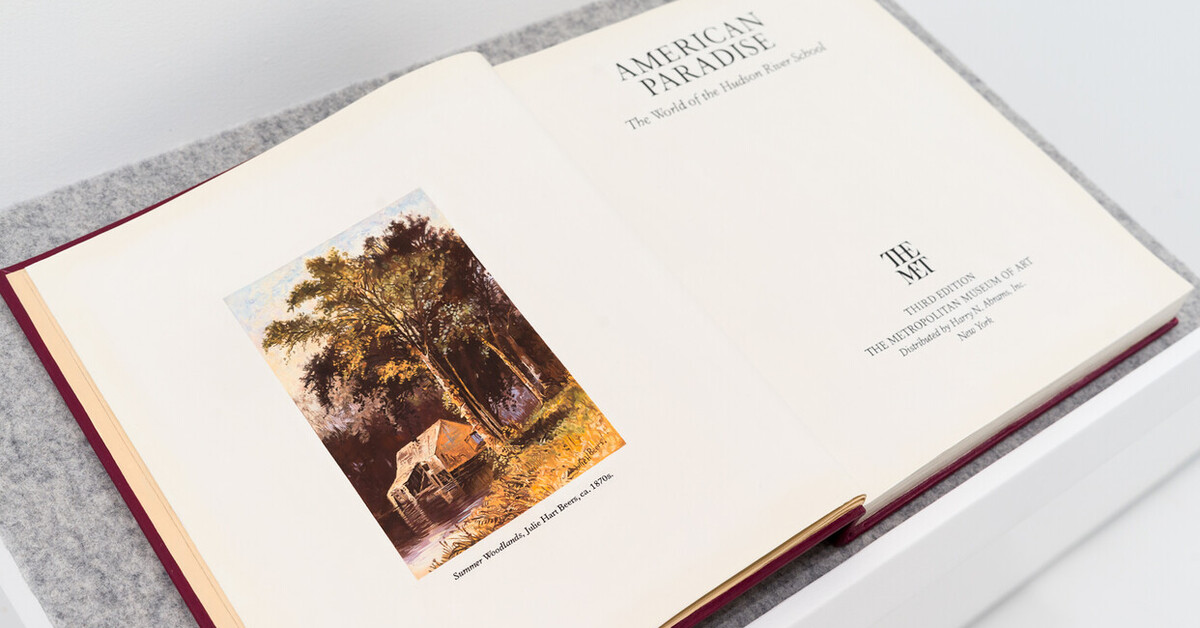

For example, if you want to learn more about Moyra Davey’s photographic series Visitor (2022), you are directed by the wall label to find “o5x” in the exhibition’s printed booklet (or the accompanying digital version via QR code). This mix of letters and numbers was randomly generated by the exhibition designer. It’s inventive, but visually overpowers the already crowded room. Over 40 artists share the small space.

And yet, attempting to navigate the exhibition through this unfamiliar system is actually quite effective. It replicates the confusion and bewilderment of the pandemic, when we became accustomed to looking to makeshift signs for guidance on how to behave (wear a mask, stand six feet apart, etc.). Like those COVID-era signs, the information connected to KADIST’s labels can be crucial.

Under “b5a,” the booklet reveals insight on Sherrill Roland’s hard-edged minimalist wall sculpture that adds depth and poignancy to the piece. In the curator’s text on the work we learn of Roland’s wrongful incarceration, and that the Kool-Aid-tinted geometric steel forms are the traced outlines of cinder blocks from his prison cell.

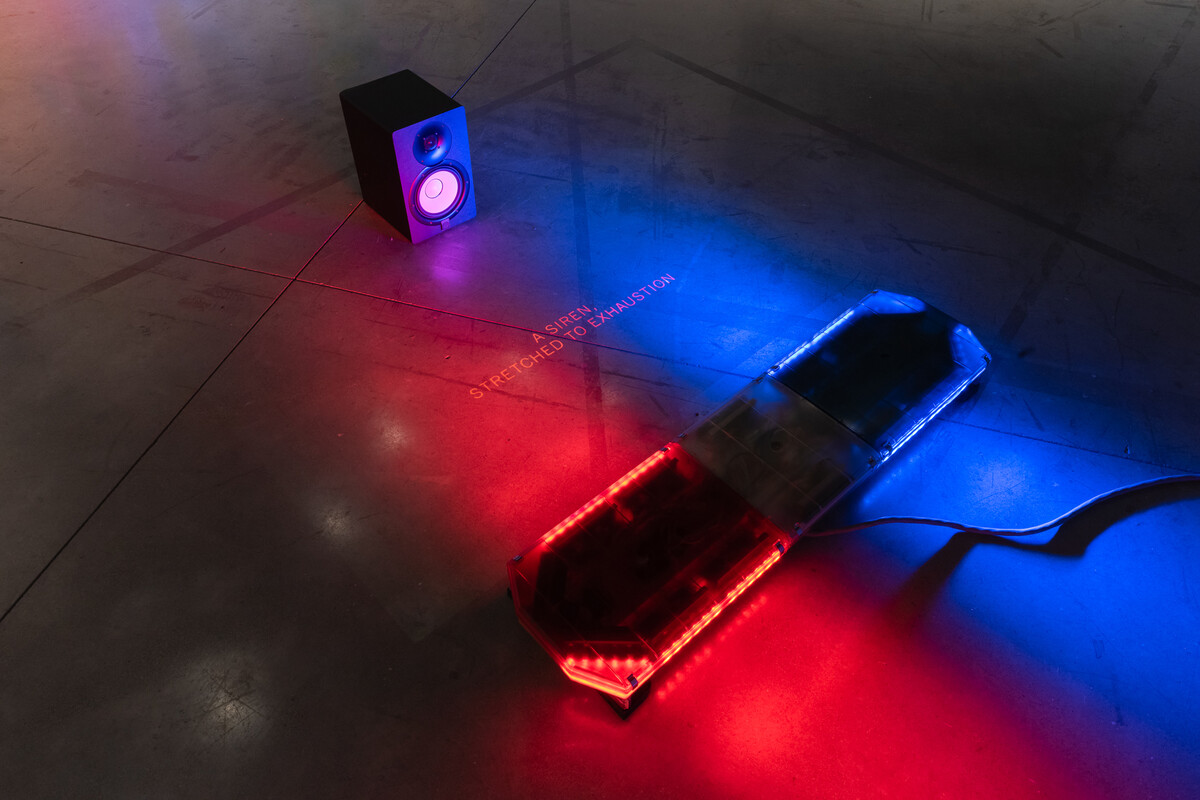

Joe Namy, ‘Half Blue,’ 2019. (Courtesy of the artist, KADIST collection; Photo by Phillip Maisel)

So-called “anchor works” are installed across the three sections of the show. In the second room, a series of 21 videos project one after another on a single hanging screen, turning off at intervals to make space for a 10-minute sound and mixed media sculpture by Joe Namy, Half Blue (2019). This is the room’s anchor: red and blue flashing lights from the top of a police car, positioned on the floor in front of the screen. As they flash, a mix of sounds plays, including news broadcasts covering the murder of the artist’s cousin, Khalid Jabara.

Jabara and Heather Heyer’s murders led to the NO HATE Act, passed by Congress in 2021. Namy’s piece is solemn in its directness. The LED light bar lies prone on the floor, its wires exposed, nearly abstract when not in use. When it plays it saturates the surrounding art in emergency-coded light.

Jamel Robinson’s sculpture I Walked The Longest Mile To Get To Nowhere Still (2022), anchors the third room. This raw assemblage of ready-mades refers to the origins of slavery in America and the devaluation of Black and brown life. The backrest of a simple wooden chair is adorned with shiny copper pennies, and a clumped mass of white rice is glued to the seat from which long nails protrude unevenly. A limp ladder of rusted chains and a pair of army boots lead up to the chair’s legs on the floor. The piece benefits from its scrappiness and lack of polish, even if every signifier is meant to be taken rather literally.

Installation view of ‘Makeshift Memorials, Small Revolutions’ with Jamel Robinson’s ‘I Walked The Longest Mile To Get To Nowhere Still,’ 2022 in the foreground. (Courtesy of the artists, KADIST collection; Patron Gallery; Photo by Phillip Maisel)

Makeshift Memorials offers an incredibly diverse range of global artworks, made mostly over the last four years, all chronicling weighty, devastating topics. And although each piece supports the curatorial premise in some way, formally they didn’t seem to relate to one other — despite a shared seriousness and the strength of their individual parts.

Attempting to distill something as broad and recent as the impact of the pandemic onto a few walls is a formidable task. Even an exhibition with limitless space couldn’t fully represent that experience. Instead, here we have a poetic churn of works that address the issues at hand piecemeal: violence, marginalization, illness, isolation, grief. I came away from the show emotionally drained, but with a heightened sensitivity to the breadth of vulnerability that connects and defines human life.

‘Makeshift Memorials, Small Revolutions’ is on view at KADIST (3295 20th St., San Francisco) through Feb. 15 2025. A concurrent exhibition at the Blaffer Art Museum in Houston is on view through March 9, 2025.