Mika Horibuchi Made Her Name Repainting the Work of Another Artist: Her Grandmother

Cultured / Nov 21, 2024 / by Max Lakin / Go to Original

The Chicago-based artist joins a long lineage of artists who’ve found creative fulfillment in facsimiles.

AGE: 33

BASED IN: Chicago

“When I was younger, I learned to draw by copying images—essentially without even realizing it,” Mika Horibuchi tells me from her Chicago studio. “That’s a pretty universal starting point. The inclination to imitate is natural.”

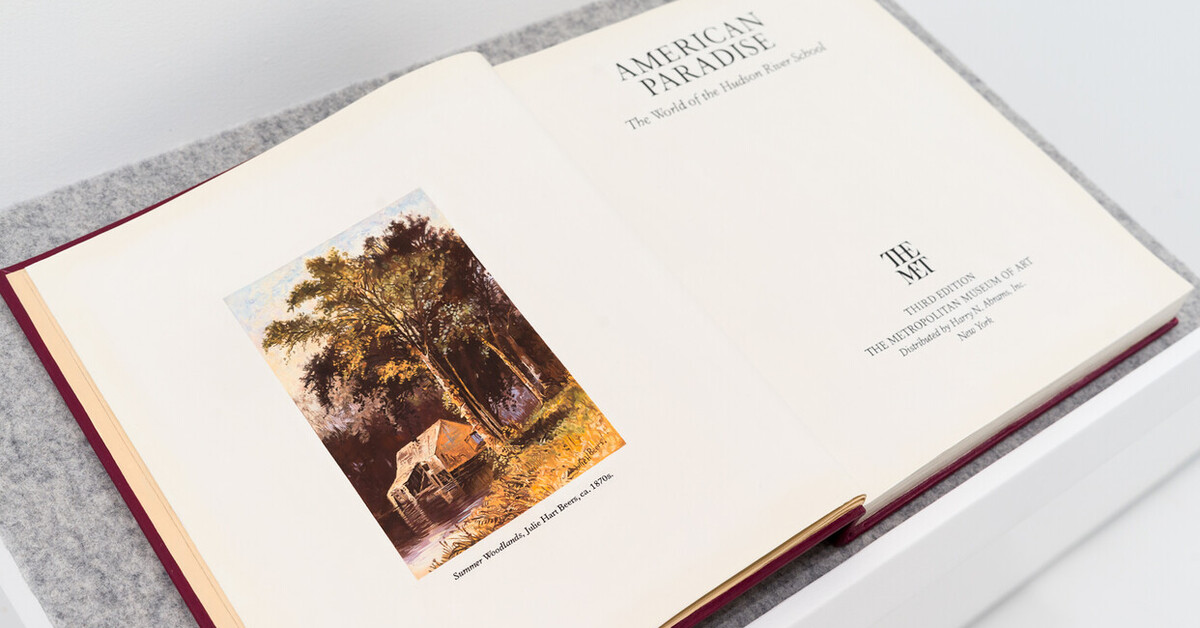

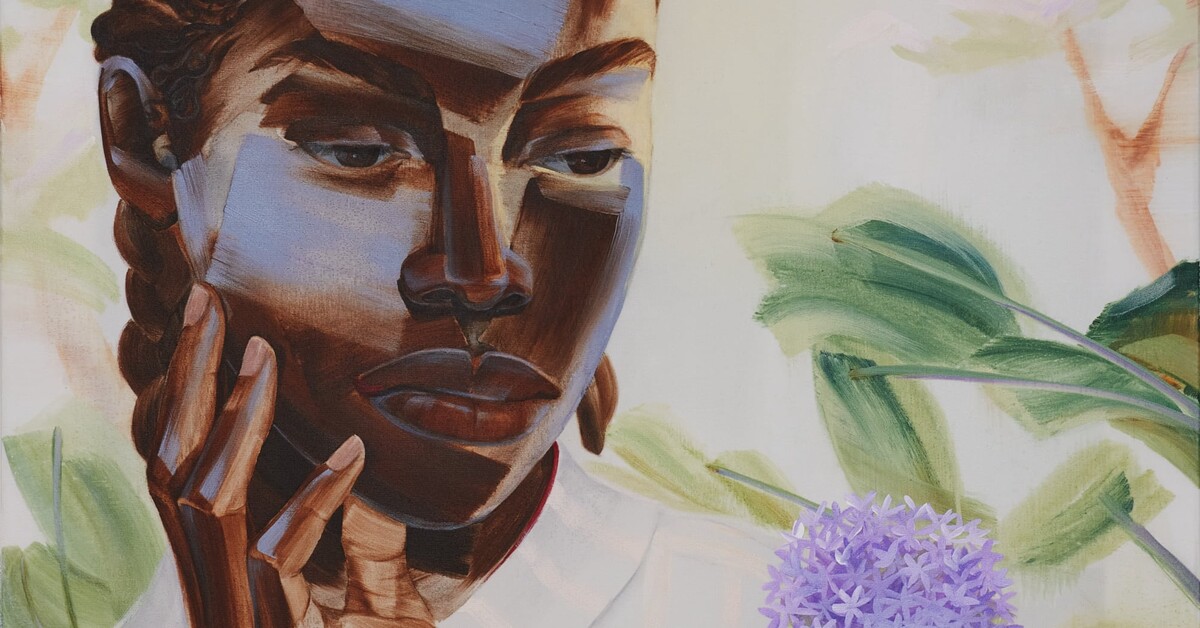

Horibuchi’s paintings extend the biological imperative for mimicry toward its conceptual limit. Her delicate watercolors of pretty landscapes and flower still lifes are, in truth, oil reproductions of photographs of delicate watercolors of pretty landscapes and flower still lifes, painted by her grandmother. Horibuchi’s versions pan out to reveal the trick, including the linen backing. “There’s a blunt and transparent approach to it all,” the artist says. “My intention is to put artifice onto the surface. To reveal the deception. To create space for new meaning.”

Like Vija Celmins and Rudolf Stingel, whose artistic outputs involve faithful facsimiles of images degrees-removed from their origins, Horibuchi is interested in the act of seeing. But her practice also considers Magritte’s warning of The Treachery of Images, an exegesis into the knotty realm of perception and subjective reality—being able to trust our eyes when they tell us we’re looking at a pipe, or a watercolor still life of cherry blossoms. Horibuchi’s compositions make plain the suspension of disbelief all art asks us to exercise—what she calls “the willingness toward magical thinking.” Her work attempts to pinpoint where a fiction begins, and where it falters.

“Copying to me is a form of translation,” the artist says. “Even simply looking at something, there’s always distance there. With copying, I’m interested in the multiple stages of translation, sometimes mistranslation of a source, and how representations of representations can become originals.” Her investigations look toward the goal of creating a reactive spiral—something that begins to copy or reference itself. As for imitating her grandmother’s watercolors? “They don’t really get easier for me,” she says, “which I think is a good thing.”

Photography by Drake Sweeney.

AGE: 33

BASED IN: Chicago

“When I was younger, I learned to draw by copying images—essentially without even realizing it,” Mika Horibuchi tells me from her Chicago studio. “That’s a pretty universal starting point. The inclination to imitate is natural.”

Horibuchi’s paintings extend the biological imperative for mimicry toward its conceptual limit. Her delicate watercolors of pretty landscapes and flower still lifes are, in truth, oil reproductions of photographs of delicate watercolors of pretty landscapes and flower still lifes, painted by her grandmother. Horibuchi’s versions pan out to reveal the trick, including the linen backing. “There’s a blunt and transparent approach to it all,” the artist says. “My intention is to put artifice onto the surface. To reveal the deception. To create space for new meaning.”

Like Vija Celmins and Rudolf Stingel, whose artistic outputs involve faithful facsimiles of images degrees-removed from their origins, Horibuchi is interested in the act of seeing. But her practice also considers Magritte’s warning of The Treachery of Images, an exegesis into the knotty realm of perception and subjective reality—being able to trust our eyes when they tell us we’re looking at a pipe, or a watercolor still life of cherry blossoms. Horibuchi’s compositions make plain the suspension of disbelief all art asks us to exercise—what she calls “the willingness toward magical thinking.” Her work attempts to pinpoint where a fiction begins, and where it falters.

“Copying to me is a form of translation,” the artist says. “Even simply looking at something, there’s always distance there. With copying, I’m interested in the multiple stages of translation, sometimes mistranslation of a source, and how representations of representations can become originals.” Her investigations look toward the goal of creating a reactive spiral—something that begins to copy or reference itself. As for imitating her grandmother’s watercolors? “They don’t really get easier for me,” she says, “which I think is a good thing.”