A powerful show at MECA&D raises questions about the display of art

Press Herald / Nov 25, 2024 / by Jorge S. Arango / Go to Original

Gala Porras-Kim, “Leaving the institution through cremation is easier than as a result of a deaccession policy,” 2021. Photos by Joel Tsui/courtesy of the ICA at MECA&D

‘Objects and Power’ at the Portland art college’s Institute of Contemporary Art explores repatriation, museum curatorial practices and much more.

“Leaving the institution through cremation is easier than as a result of a deaccession policy” is a piece by Colombian-Korean-American artist Gala Porras-Kim in “Objects and Power,” the current exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art at the Maine College of Art & Design (through Dec. 13). It outlines one of many poignant issues covered in this museum’s show, which is about museums and their practices.

The work consists, in part, of a letter from the artist to the director of the National Museum of Brazil about “Luzia,” a 12,000-year-old human fossil of a young Clovis woman, part of a group of hunter-gatherers who had migrated from North America down through South America in pursuit of megafauna like the giant sloth and mammoth.

“In the past, I have had many conversations with various museum staff to understand the conditions of people being stored throughout institutions such as yours,” reads the document. “Their remains, which are material parts of people who are unable to directly express and determine how they are kept, provoke several questions about their current existence in the museum — out of their final resting place …”

About 80 percent of Luzia’s skull was salvaged from a 2018 fire at the museum, and the institution has since tried to gather what it can of the cremains in an effort to reassemble Luzia using DNA evidence imbedded in them. “These efforts are done to prevent the current physical deterioration of ‘Luzia’ as an object and not prioritizing what her wishes for her afterlife might have been,” Porras-Kim continues. Further down she writes “you might try to see her personhood, and she stops being merely an object in the collection. Then I would like to propose incinerating the rest of her remains because when you let go of the shape you think she should be as an object, she will return to her life as a corpse once again.”

You might gather from this work that the exhibition is an anti-institutional jeremiad about colonialist practices of preservation, research and archiving of Indigenous people and artifacts. Repatriation of what is considered cultural property, after all, is a persistent discussion in the museum world, one that continues to elude resolution. Some major institutions argue that museums are repositories of knowledge and promote its dissemination as well as understanding of history and peoples, while others point out that museums are filled largely with art and artifacts looted from their places of origin by colonial powers.

Maya Tihtiyas Attean (member of the Penobscot Nation), “Mikwidahamin/Portal,” 2024.

But one of the show’s greatest strengths is that it stirs contemplation rather than self-righteousness. Take works by SaraNoa Mark and Penobscot artist Maya Tihtiyas Attean. They are among the artists who wrote their own wall labels, and theirs struck me as atypical, in their extremely personal nature, of the usual sort of clinical explication offered by institutions. There is little overtly political statement here, no brow-beating or museum jargon. Instead, we are left with a melancholy sense of each work’s innate poetics.

Mark’s installation originates from a stint as a security guard at Chicago’s Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures (formerly called the Oriental Institute) as the museum prepared for its centennial exhibition. The work consists of armatures specially made to hold objects from the collection, each metal form disguised by materials or colors that mimicked the materials or colors of the object they held.

“I found myself … watching over a collection of empty cases,” Mark writes. “The experience of guarding absence evoked an acute awareness of the artifacts’ presence far from their points of extraction … Devoid of the objects the armatures were designed to support, this installation employs an institutional alphabet to contemplate the absence of objects displaced from their places of origin.”

SaraNoa Mark, “Guarding Invisibility,” 2019.

Indeed, the armatures can be read as a kind of writing system. But there is also both sadness here (in the reflection they prompt about the objects’ deracination and the fact that they may be sitting on a shelf in a backroom of a museum somewhere) as well as a mild aggression (the installation feels like a gauntlet, with the armatures appearing like spiders waiting to snag our own memories and beinghood into their webs).

Attean’s label for “Mikwidahamin/Portal” begins with a sobering statement: “Colonialism and capitalism value objectification, commodification, and control over all. The colonialists began by dispossessing and disconnecting Indigenous people from the land, collecting our bodies and artifacts…”

But the Portland-based Attean quickly moves into more heart-centered musings about what is collected in her explanation of the personal significance of the piece, a contemporary version of a fishing weir built many years ago that still exists today. “Mikwidahamin means ‘remember me’ in Passamaquoddy,” she writes. “This phrase helps me realize that objects are created as part of our extension of energy.” The phrase, she continues, “served as a subtle reminder that the objects we create are more than simply things – they are part of our story, our lineage, our legacy. The energy and spirit within each object we create cannot ever be tangibly collected.”

Stephanie Syjuco, “Block Out the Sun,” 2021.

Both labels emphasize the meaning and life of objects over the institutional penchant for merely viewing them scientifically as curiosities. Which is not to say the whole show is lacking in disturbingly confrontational work. A video by Philippine-born American artist Stephanie Syjuco interrogates the perverse voyeurism of the 1904 St. Louis World’s Fair, for which organizers imported people from the Philippines (and other locales) and placed them in sets that re-created their home villages. Viewers were invited to ogle these “exotic” peoples in ways that feel, by today’s standards, uncomfortably like carnival oddities and “freaks.”

Syjuco, who lives in Oakland, presents a slide show of these exhibits, but in each uses her hand to obscure the faces and/or bodies of the human beings in the scenes. Yet even though we are uncomfortably challenged to examine our own primitive “othering” instincts, the act of Syjuco obscuring these people feels protective, restoring some of their natural dignity.

Samuel Levi Jones, “The Library of Alexandria,” 2023.

The works explore many more issues. In “The Library of Alexandria,” Indiana-based artist Samuel Levi Jones examines the way knowledge is collected, organized and lost (sometimes through accidental destruction, sometimes intentionally through erasure or concealment). This elegantly conceptual structure repurposes shelving systems onto which he has placed simulacra of encyclopedias made from actual encyclopedia paper pulp poured into book-shaped molds.

On his wall label, the African American artist notes that these faux books are “Inviting perusal yet alienating content … (reflecting) on how information has been and continues to be systematically denied, excluded, and erased.” He is speaking here, of course, about research that may never see the light of day, but also about the art of marginalized groups that is often denied the opportunity of exhibition in institutions.

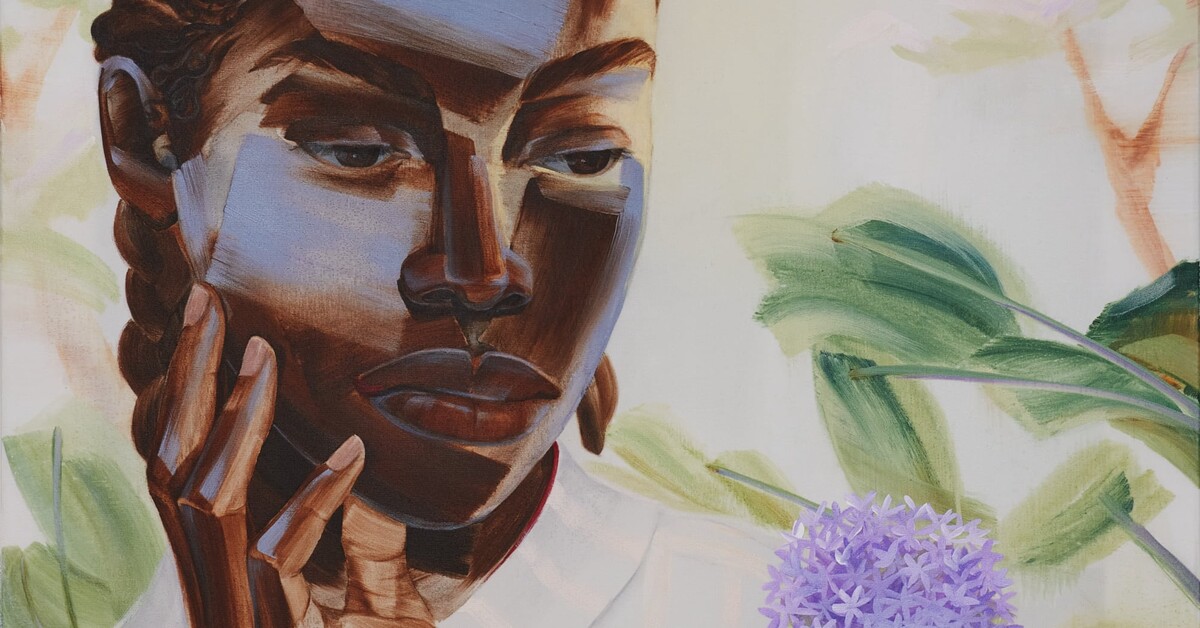

Morehshin Allahyari, “Moon-faced,” 2022

Moreshin Allahyari, an Iranian-Kurdish artist who splits her time between New York and the San Francisco Bay Area, examines the depiction of gender in art. “Moon-faced” takes its name from a descriptor of beauty in Persian literature that, during the Qajar Dynasty in Iran (1789-1925), was used without regard to gender. Today, however, it is employed only to describe women’s beauty. This, she notes in her wall label, “overshadowed and ended the queer representation of genders that historically characterized (Qajar dynasty portrait painting), largely known for their gender-undifferentiation.” Using AI technology, she creates a video that weaves elements of these paintings in an ever gender-morphing meditation.

Believe it or not, this is just the tip of the iceberg. The exhibition presents so many questions: about how art and artifacts are exhibited, how their meanings shift with changes in political thought and cultural awareness, about the inescapably filtered view of museum curation, about what and who confers value on this or that art. It is one of the most absorbing and thought-provoking exhibits around. Don’t miss it.