Beginnings and Endings

Beyond Noise / Jun 20, 2024 / by Megan Hullander / Go to Original

IN THE SHADOW OF NORWAY’S MOUNTAINS, CATHERINE OPIE CHASES THE COLOR BLUE. CARMEN WINANT JOINS THE PHOTOGRAPHER TO DISCUSS THE INTENTION BEHIND HER LATEST WORK.

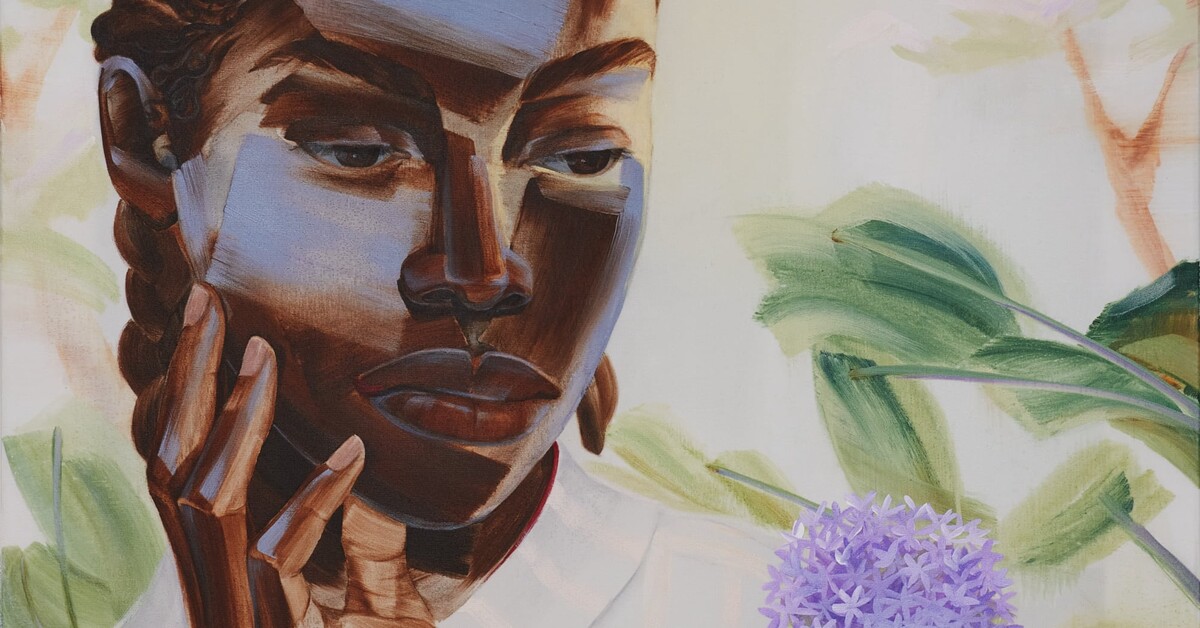

Catherine Opie finds humanity everywhere. She’s perhaps best-known for documenting cultural phenomena in rich color, finding vulnerability in tender portrayals of the American underbelly—stringing a thread between expressionistic landscapes and those who inhabit them. Inarguably radical, she portraits distinctive, unconventional personalities. The work’s draw isn’t in that difference, however, but in its confessional sentiment—Catherine and her subject offering a piece of themselves to the overall composition. This intimacy makes her work widely resonant, cementing her place in art history—earning her endowed chair of UCLA’s art department, a board position at MoCA, and space in the collections of MoMA and the Guggenheim.

The works Catherine produces require her to listen and really look at the environments she chooses to document. The photographs of her most recent series, Beginnings and Endings, exhibit that compassion. “Why does a portrait of a person take precedence over a portrait of a mountain?” she asks. A landscape, almost always, is marked by its width and its breadth; the images capture layers of hills and swaths of brush and edges of bodies of water. But here, the photographer looks at their depth, rendering her landscapes vertically: a few crests of a cliff face and everything beneath it; just the peak of a mountain and the sky stretching above it.

On the heels of her decades-long career in academia, Catherine was finally able to take a long-anticipated trip: In January, she ventured to the mountains of Norway to chase the color blue. It’s a persistent muse for creative minds: the cerulean blues of the Impressionists, the metaphorical blues of Joan Didion, the anguished blues of Picasso, the monochromes of Yves Klein. The blues that Catherine found reckon with the color’s history—what it holds, why we’re drawn to it—placing it in a new context that’s the sum of those many interpretations. The blues she encountered in the mountains and the sky and the snow are sublime—natural and otherworldly at once.

This philosophical immensity is something Carmen Winant, Catherine’s former student and fellow artist, grapples with, too. Her work deals with contradictions in women’s power, pleasure, and liberation—seeking primary evidence in found photographs to recontextualize topics that feel familiar, like childbirth and abortion. Her book My Birth contains 2,000 photographs of women in labor, asserting that there is no one way to bear witness to an experience, no matter how ubiquitous it is. In the same spirit as Catherine, she uses the emotional resonance of imagery to prompt new ways of seeing.

For Beyond Noise, Catherine and Carmen meet to unravel the intentions behind Beginnings and Endings, and the weight of perspective.

CARMEN WINANT: Much has been written about the ways your practice encompasses both landscapes and portraits, of the way that you draw them closer together—teasing out the subjectivity of the physical world and the way in which the landscape is itself a body. I was struck by the verticality of these most recent pictures. This is not a conventional way to approach landscape. How much were you thinking about that literally, in relation to approaches to photographing the body?

CATHERINE OPIE: A lot, because I was trying to make portraits. This is a portrait format, not a landscape format—but I’ve been making vertical landscapes for a really long time now. It started with Icehouses, and I’ve made some abstract ones that were quite big, kind of the sizes these will be printed at. They end up creating a space and a feeling that lead you to question what you’re looking at. I want people to spend as much time with the photograph as possible. I’d like to think that if people came back to these images every day, they would see something different—that the photograph is always revealing itself in different ways.

I wanted to think about the specificity of identity in places, as I’ve done in other bodies of work, as well as the specificity of blue and the artists who’ve used blue. I printed one yesterday and it’s like an Yves Klein blue—how the hell did I get that? It’s really interesting when you think about being in a place such as Norway, where you’re living with the grandest landscape you could ever imagine. I go through a sense of awe and inspiration, but at the same time, people are living there every day. Those are just their landscapes. That’s their mountains. I don’t even know if they go, like, “Wow!” anymore because they’ve lived in the same house overlooking a fjord for 30 years. You’re gonna see every amazing light thing that nature can do through the seasons. I wanted to see if I could make portraits that would be unfamiliar to the people who lived there.

What is it to serve a community in looking at a place? When people looked at Icehouses in Minnesota, they felt that I captured their landscape in a very specific way. There’s something within these adventures that isn’t just about fulfilling my need—it’s a gift back to a place.

CW: Could you talk a little bit about the amount of sky? That felt quite unfamiliar to me. It became a positive space instead of a negative space, maybe partially because of how saturated it is. But there are some photographs that felt to be predominantly sky—almost like an inversion of Surfers, actually.

CO: That’s what I was looking for. I really wanted that blue. I wanted to see if that blue could be photographed. I remember having a really interesting conversation with an architect from Norway—we were in Rome together talking about the blue light, and apparently, I didn’t go far enough north for the true blue. I might still be chasing the blue of Norway in that way, but I’m not sure.

CW: What makes it a true blue? That it’s the deepest saturation?

CO: Yes… It’s this color people talk about during this time of year. Obviously, people talk about the northern lights and I would have loved to have seen that. I would have photographed it, even though it would have bumped up against the cliché. I really wanted to describe that surface space with that sky space, in the same way that Icehouses was photographed in blizzards; something flattens out in relation to the color, but also feels utterly expansive. Does that change your state of being when you’re standing before the print?

CW: “Expansive” is the word for it.

CO: And the idea of transcendence in a certain way, and how do you get there?

CW: You keep using the word “feeling.” That’s a word that I remember you using a lot as my teacher; you really encourage that. I don’t know if you remember this, but when I was taking pictures of runners—my teammates—you emphasized feeling inside this institution where I felt such pressure to be an expert. Everything was about cerebral inquiry. I wonder how you situate and make an argument for feeling—an impulse some might question as anti-intellectual.

CO: That’s the thing: Art school maybe has ruined us about feelings.

CW: A little bit, I think.

CO: That’s a little bit of a problem.

CW: Right, but you’re wrestling it back.

CO: It makes me think of Judith Butler’s new book, Who’s Afraid of Gender? This book came from a place of feeling, from one of the most brilliant and hardest writers to read, theoretically in relation to the construct of gender. Gender Trouble was the book of the ’90s, but it was kind of void of the notion of feeling. The new book opens with an account of Butler’s assault in Brazil and the burning of their effigy in response to their beliefs. So, all of a sudden, someone who is so invested in the theoretical world has these feelings—so much so that they need to readdress their own work. It comes out of feelings, a quandary of other things. I think that we forget this as human beings.

CW: At least within the context of the academic institution—and maybe I’m projecting—I feel like I’ve always had to hold that part close. I credit you with giving me permission to do that even before I could identify what was happening. Perhaps we should talk more about the blue?

CO: Yeah, what is the blue? The blue comes very much from Rebecca Solnit—her A Field Guide to Getting Lost. I had already been making work that ranged in blue, like Surfers, trying to figure it out because I wanted that fog of the coast. I wanted that horizon line to begin to disappear. Then I went to Alaska and did a piece, an homage to Rebecca Solnit, called Blue of Distance, which is this series of landforms getting closer and changing on the way out to the ocean. Then Twelve Miles to the Horizon, where I traveled on a container ship from the Port of Busan to the Port of Long Beach and photographed every sunrise and sunset. There were all these different levels of blue in that. So when I went to Norway for the first time in the winter, 13 years ago, I took a photograph outside under this three o’clock blue light. That was just the most magical light I’ve ever seen. Being in California, light is just there, so to all of a sudden have this portrait washed out in colors of blue was just astounding to me. I said, “I’ve got to come back and try to chase this blue. I gotta know this blue.”

CW: I love the idea of you chasing blue or adding variations to your palette over so many years. You talk about growing up in Sandusky and the blueness and the atmosphere over the lake. Of course, here in Columbus, Ohio, I don’t have any access to that blue—we’re landlocked. A fact that I heard many years ago dislodged in my brain when I was looking at the pictures—about how ancient language didn’t have a word for the color blue.

CO: This is true. I read this as well.

CW: What do you think about this? In The Odyssey, Homer doesn’t have a word for the sea. He describes it as “wine dark,” which of course is not the color of the sea.

CO: It became so valuable. Michael Baxandall writes about the blue of painting becoming the iconic color that all the upper aristocrats wanted. It showed this idea of purity and wealth because it was such a rare pigment. I remember being blown away by that at CalArts.

CW: This was when you were a grad student? As long ago as that you were thinking about this color?

CO: I think it’s always been my favorite color; I think there’s even a butchness to blue. It was so hard for me to identify with pink. I had a blue baby blanket growing up. This baby blanket got taken away from me at the age of eight. I was very attached to it. My dad threw it away and it was heartbreaking. It was the same color as Linus’s blanket. I remember, when I had Oliver—and you might remember this too as a mom—when it goes to dusk, all babies are just like, “Aaaah!” They go through this stage, this transition…

CW: Yeah, the witching hour.

CO: The witching hour. There’s something about it that has this poignancy that hasn’t been explored enough.

CW: I’m even thinking about the seamless backgrounds you’ve used in the studio—not just the blue, but the level of saturation. Your work has been always described as painterly, but I remember being frightened of your photographs for that reason—the evenness and the depth of the background. There was something about that that came through in these pictures. I remember working in your studio, and it was always like that—a deep, deep opaque color. What is in that for you? Maybe you can’t answer that.

CO: I think other people have answered it for me. Richard Flood, who knew Robert Mapplethorpe really well—a lot of people talked about my work in relation to Mapplethorpe, because of the formality and sexuality combined—said, “One of the things that Robert could never figure out was color, and you figured out color in a way that would have really pissed him off.”

CW: The highest compliment! [Laughs]

CO: [Laughs] Yes, the highest compliment. I think people don’t allow color to be as bold as it can be. If you’re gonna take color photographs, then you might as well really try to work with what color does. It was just through my lighting and how I light to get that saturation; nobody had really done that before.

CW: It’s so funny because I’ve always known you to wear all black.

CO: [Laughs] I wear color here and there.

CW: I saw this talk by Jeff Wall where he described photographing quite intentionally in shallow space, in the most controlled possible manner. I thought, That’s why I feel so claustrophobic looking at these photographs. I’ve always thought of you as a counter to that approach—as a photographer of deep space. You’ve talked about how these landscapes aren’t necessarily here for us. They’re not inviting us in, they’re not places to enter, and yet, at the same time, they are deep space.

CO: Deep space, but also flattened space, too.

CW: How do you think about their relationship? Do you think about yourself as a photographer of deep space?

CO: I think about space all the time as a photographer, because that’s what begins to create the way you enter or exit any image. I think about space differently if I’m doing a body of work like what I did in 2020, in an RV photographing monuments and things like that.

That space is the space of a documentary. On the other hand, if I want to transform photography in relation to how we think we know it, with bright saturated colors, even someone who knows me well will slip up and call my work “paintings.”

We think we know what photography does—ultimately, it’s about a kind of representation. But by watching and spending time with light and being deliberate, you can create an illusion of whether or not what you’re looking at is real—especially since digital photography and now AI has taken over in such a big way. This idea of space is a way of holding the viewer, and we have to hold them by not tricking them with illusion; not building through a computer, but through the act of making and the consistency that you provide in making the body of work.

CW: It feels like there’s something about the shallow space of photographing in the studio, where the seamlessness blocks you. I was just reading Pageboy, the Elliot Page memoir, and looking at your photograph on the cover—you can’t enter beyond that. There’s a profound intimacy to that.

CO: It’s about what we expect of photography. That’s the thing. Our expectations of photography are really funny; people are really funny about what constitutes photographic space. Wall was playing with it in the way that was making something epic, but reducing it spatially. He was dealing with tableaux, he was dealing with all of these other things—about how an image is constructed and the notion of construct more than the viewer experiencing it.

CW: I totally get what you’re saying—it’s much more obviously constructed. There’s always the brick wall four feet behind, and it feels like the way it’s constructed is to feel so constricting. I never feel constricted in your photographs. It does come down right back to feeling.

CO: That’s part of this idea of humanity, too. I don’t want the constriction because I want you to have an experience that recognizes what I’ve tried to do. I want the experience to be one where the viewer has space for a potential meditation, a recognition that we’re so little as a species in relation to the largeness of this. Why does a portrait of a person take precedence over a portrait of a mountain?

CW: “A portrait of a mountain.” I’ve never heard that phrase before but it feels, of course, very fitting here. You’re entering this new phase of your life in lots of different ways and standing in front of… I don’t know how many millions of years old these pieces of earth are, but there are mountains in South Africa that are three and a half billion years old. So how do you think about their long-standing body in relation to your slightly less long-standing body that’s moving through phases of life?

CO: You’ve asked the most important question. They were bodies before the borders, before the political, before what I’m witnessing right now in this country, in America, in relation to abortion, to what happened in Arizona yesterday, to what is happening with over 600 anti-trans pieces of legislation being adopted toward bodies that are themselves transforming. These mountains are there, always, but they transform in all of these ways through the continuum of their lives, what they hold, and the way that water comes down every year and grooves them—like a piercing or a scar or the wrinkles on my face change my own body. I’m very connected to the idea of how short a life I will have, compared to what it is to bear witness to these forms. That’s why I’m making portraits of them. It is so important to remind people that this is significant and there was a time without borders or boundaries. That all of this earth was made, and what we have done as a species to interrupt this. That’s also why images of Norwegian towns and human activity are there, too, to remind you of our own humanness, to control these environments.

CW: A time without borders feels almost impossible to imagine. It reminds me of my older kid, who’s eight now and is learning about history in school. He situates things by looking at the magnolia tree in the backyard. He says, “Is that magnolia tree older than the Civil Rights Movement?” He’s situating his relative understanding of historical time and place in relation to nature. And in doing that, he’s grappling with how old nature is, how cyclical, but also how all the trees around our neighborhood are older than he is. That is a huge psychic change in his little mind.

CO: That’s amazing, because it’s another way of figuring out how to tell time. What is the relationship to time and my being and all of that, and how do I situate myself in this?

Catherine Opie finds humanity everywhere. She’s perhaps best-known for documenting cultural phenomena in rich color, finding vulnerability in tender portrayals of the American underbelly—stringing a thread between expressionistic landscapes and those who inhabit them. Inarguably radical, she portraits distinctive, unconventional personalities. The work’s draw isn’t in that difference, however, but in its confessional sentiment—Catherine and her subject offering a piece of themselves to the overall composition. This intimacy makes her work widely resonant, cementing her place in art history—earning her endowed chair of UCLA’s art department, a board position at MoCA, and space in the collections of MoMA and the Guggenheim.

The works Catherine produces require her to listen and really look at the environments she chooses to document. The photographs of her most recent series, Beginnings and Endings, exhibit that compassion. “Why does a portrait of a person take precedence over a portrait of a mountain?” she asks. A landscape, almost always, is marked by its width and its breadth; the images capture layers of hills and swaths of brush and edges of bodies of water. But here, the photographer looks at their depth, rendering her landscapes vertically: a few crests of a cliff face and everything beneath it; just the peak of a mountain and the sky stretching above it.

On the heels of her decades-long career in academia, Catherine was finally able to take a long-anticipated trip: In January, she ventured to the mountains of Norway to chase the color blue. It’s a persistent muse for creative minds: the cerulean blues of the Impressionists, the metaphorical blues of Joan Didion, the anguished blues of Picasso, the monochromes of Yves Klein. The blues that Catherine found reckon with the color’s history—what it holds, why we’re drawn to it—placing it in a new context that’s the sum of those many interpretations. The blues she encountered in the mountains and the sky and the snow are sublime—natural and otherworldly at once.

This philosophical immensity is something Carmen Winant, Catherine’s former student and fellow artist, grapples with, too. Her work deals with contradictions in women’s power, pleasure, and liberation—seeking primary evidence in found photographs to recontextualize topics that feel familiar, like childbirth and abortion. Her book My Birth contains 2,000 photographs of women in labor, asserting that there is no one way to bear witness to an experience, no matter how ubiquitous it is. In the same spirit as Catherine, she uses the emotional resonance of imagery to prompt new ways of seeing.

For Beyond Noise, Catherine and Carmen meet to unravel the intentions behind Beginnings and Endings, and the weight of perspective.

CARMEN WINANT: Much has been written about the ways your practice encompasses both landscapes and portraits, of the way that you draw them closer together—teasing out the subjectivity of the physical world and the way in which the landscape is itself a body. I was struck by the verticality of these most recent pictures. This is not a conventional way to approach landscape. How much were you thinking about that literally, in relation to approaches to photographing the body?

CATHERINE OPIE: A lot, because I was trying to make portraits. This is a portrait format, not a landscape format—but I’ve been making vertical landscapes for a really long time now. It started with Icehouses, and I’ve made some abstract ones that were quite big, kind of the sizes these will be printed at. They end up creating a space and a feeling that lead you to question what you’re looking at. I want people to spend as much time with the photograph as possible. I’d like to think that if people came back to these images every day, they would see something different—that the photograph is always revealing itself in different ways.

I wanted to think about the specificity of identity in places, as I’ve done in other bodies of work, as well as the specificity of blue and the artists who’ve used blue. I printed one yesterday and it’s like an Yves Klein blue—how the hell did I get that? It’s really interesting when you think about being in a place such as Norway, where you’re living with the grandest landscape you could ever imagine. I go through a sense of awe and inspiration, but at the same time, people are living there every day. Those are just their landscapes. That’s their mountains. I don’t even know if they go, like, “Wow!” anymore because they’ve lived in the same house overlooking a fjord for 30 years. You’re gonna see every amazing light thing that nature can do through the seasons. I wanted to see if I could make portraits that would be unfamiliar to the people who lived there.

What is it to serve a community in looking at a place? When people looked at Icehouses in Minnesota, they felt that I captured their landscape in a very specific way. There’s something within these adventures that isn’t just about fulfilling my need—it’s a gift back to a place.

CW: Could you talk a little bit about the amount of sky? That felt quite unfamiliar to me. It became a positive space instead of a negative space, maybe partially because of how saturated it is. But there are some photographs that felt to be predominantly sky—almost like an inversion of Surfers, actually.

CO: That’s what I was looking for. I really wanted that blue. I wanted to see if that blue could be photographed. I remember having a really interesting conversation with an architect from Norway—we were in Rome together talking about the blue light, and apparently, I didn’t go far enough north for the true blue. I might still be chasing the blue of Norway in that way, but I’m not sure.

CW: What makes it a true blue? That it’s the deepest saturation?

CO: Yes… It’s this color people talk about during this time of year. Obviously, people talk about the northern lights and I would have loved to have seen that. I would have photographed it, even though it would have bumped up against the cliché. I really wanted to describe that surface space with that sky space, in the same way that Icehouses was photographed in blizzards; something flattens out in relation to the color, but also feels utterly expansive. Does that change your state of being when you’re standing before the print?

CW: “Expansive” is the word for it.

CO: And the idea of transcendence in a certain way, and how do you get there?

CW: You keep using the word “feeling.” That’s a word that I remember you using a lot as my teacher; you really encourage that. I don’t know if you remember this, but when I was taking pictures of runners—my teammates—you emphasized feeling inside this institution where I felt such pressure to be an expert. Everything was about cerebral inquiry. I wonder how you situate and make an argument for feeling—an impulse some might question as anti-intellectual.

CO: That’s the thing: Art school maybe has ruined us about feelings.

CW: A little bit, I think.

CO: That’s a little bit of a problem.

CW: Right, but you’re wrestling it back.

CO: It makes me think of Judith Butler’s new book, Who’s Afraid of Gender? This book came from a place of feeling, from one of the most brilliant and hardest writers to read, theoretically in relation to the construct of gender. Gender Trouble was the book of the ’90s, but it was kind of void of the notion of feeling. The new book opens with an account of Butler’s assault in Brazil and the burning of their effigy in response to their beliefs. So, all of a sudden, someone who is so invested in the theoretical world has these feelings—so much so that they need to readdress their own work. It comes out of feelings, a quandary of other things. I think that we forget this as human beings.

CW: At least within the context of the academic institution—and maybe I’m projecting—I feel like I’ve always had to hold that part close. I credit you with giving me permission to do that even before I could identify what was happening. Perhaps we should talk more about the blue?

CO: Yeah, what is the blue? The blue comes very much from Rebecca Solnit—her A Field Guide to Getting Lost. I had already been making work that ranged in blue, like Surfers, trying to figure it out because I wanted that fog of the coast. I wanted that horizon line to begin to disappear. Then I went to Alaska and did a piece, an homage to Rebecca Solnit, called Blue of Distance, which is this series of landforms getting closer and changing on the way out to the ocean. Then Twelve Miles to the Horizon, where I traveled on a container ship from the Port of Busan to the Port of Long Beach and photographed every sunrise and sunset. There were all these different levels of blue in that. So when I went to Norway for the first time in the winter, 13 years ago, I took a photograph outside under this three o’clock blue light. That was just the most magical light I’ve ever seen. Being in California, light is just there, so to all of a sudden have this portrait washed out in colors of blue was just astounding to me. I said, “I’ve got to come back and try to chase this blue. I gotta know this blue.”

CW: I love the idea of you chasing blue or adding variations to your palette over so many years. You talk about growing up in Sandusky and the blueness and the atmosphere over the lake. Of course, here in Columbus, Ohio, I don’t have any access to that blue—we’re landlocked. A fact that I heard many years ago dislodged in my brain when I was looking at the pictures—about how ancient language didn’t have a word for the color blue.

CO: This is true. I read this as well.

CW: What do you think about this? In The Odyssey, Homer doesn’t have a word for the sea. He describes it as “wine dark,” which of course is not the color of the sea.

CO: It became so valuable. Michael Baxandall writes about the blue of painting becoming the iconic color that all the upper aristocrats wanted. It showed this idea of purity and wealth because it was such a rare pigment. I remember being blown away by that at CalArts.

CW: This was when you were a grad student? As long ago as that you were thinking about this color?

CO: I think it’s always been my favorite color; I think there’s even a butchness to blue. It was so hard for me to identify with pink. I had a blue baby blanket growing up. This baby blanket got taken away from me at the age of eight. I was very attached to it. My dad threw it away and it was heartbreaking. It was the same color as Linus’s blanket. I remember, when I had Oliver—and you might remember this too as a mom—when it goes to dusk, all babies are just like, “Aaaah!” They go through this stage, this transition…

CW: Yeah, the witching hour.

CO: The witching hour. There’s something about it that has this poignancy that hasn’t been explored enough.

CW: I’m even thinking about the seamless backgrounds you’ve used in the studio—not just the blue, but the level of saturation. Your work has been always described as painterly, but I remember being frightened of your photographs for that reason—the evenness and the depth of the background. There was something about that that came through in these pictures. I remember working in your studio, and it was always like that—a deep, deep opaque color. What is in that for you? Maybe you can’t answer that.

CO: I think other people have answered it for me. Richard Flood, who knew Robert Mapplethorpe really well—a lot of people talked about my work in relation to Mapplethorpe, because of the formality and sexuality combined—said, “One of the things that Robert could never figure out was color, and you figured out color in a way that would have really pissed him off.”

CW: The highest compliment! [Laughs]

CO: [Laughs] Yes, the highest compliment. I think people don’t allow color to be as bold as it can be. If you’re gonna take color photographs, then you might as well really try to work with what color does. It was just through my lighting and how I light to get that saturation; nobody had really done that before.

CW: It’s so funny because I’ve always known you to wear all black.

CO: [Laughs] I wear color here and there.

CW: I saw this talk by Jeff Wall where he described photographing quite intentionally in shallow space, in the most controlled possible manner. I thought, That’s why I feel so claustrophobic looking at these photographs. I’ve always thought of you as a counter to that approach—as a photographer of deep space. You’ve talked about how these landscapes aren’t necessarily here for us. They’re not inviting us in, they’re not places to enter, and yet, at the same time, they are deep space.

CO: Deep space, but also flattened space, too.

CW: How do you think about their relationship? Do you think about yourself as a photographer of deep space?

CO: I think about space all the time as a photographer, because that’s what begins to create the way you enter or exit any image. I think about space differently if I’m doing a body of work like what I did in 2020, in an RV photographing monuments and things like that.

That space is the space of a documentary. On the other hand, if I want to transform photography in relation to how we think we know it, with bright saturated colors, even someone who knows me well will slip up and call my work “paintings.”

We think we know what photography does—ultimately, it’s about a kind of representation. But by watching and spending time with light and being deliberate, you can create an illusion of whether or not what you’re looking at is real—especially since digital photography and now AI has taken over in such a big way. This idea of space is a way of holding the viewer, and we have to hold them by not tricking them with illusion; not building through a computer, but through the act of making and the consistency that you provide in making the body of work.

CW: It feels like there’s something about the shallow space of photographing in the studio, where the seamlessness blocks you. I was just reading Pageboy, the Elliot Page memoir, and looking at your photograph on the cover—you can’t enter beyond that. There’s a profound intimacy to that.

CO: It’s about what we expect of photography. That’s the thing. Our expectations of photography are really funny; people are really funny about what constitutes photographic space. Wall was playing with it in the way that was making something epic, but reducing it spatially. He was dealing with tableaux, he was dealing with all of these other things—about how an image is constructed and the notion of construct more than the viewer experiencing it.

CW: I totally get what you’re saying—it’s much more obviously constructed. There’s always the brick wall four feet behind, and it feels like the way it’s constructed is to feel so constricting. I never feel constricted in your photographs. It does come down right back to feeling.

CO: That’s part of this idea of humanity, too. I don’t want the constriction because I want you to have an experience that recognizes what I’ve tried to do. I want the experience to be one where the viewer has space for a potential meditation, a recognition that we’re so little as a species in relation to the largeness of this. Why does a portrait of a person take precedence over a portrait of a mountain?

CW: “A portrait of a mountain.” I’ve never heard that phrase before but it feels, of course, very fitting here. You’re entering this new phase of your life in lots of different ways and standing in front of… I don’t know how many millions of years old these pieces of earth are, but there are mountains in South Africa that are three and a half billion years old. So how do you think about their long-standing body in relation to your slightly less long-standing body that’s moving through phases of life?

CO: You’ve asked the most important question. They were bodies before the borders, before the political, before what I’m witnessing right now in this country, in America, in relation to abortion, to what happened in Arizona yesterday, to what is happening with over 600 anti-trans pieces of legislation being adopted toward bodies that are themselves transforming. These mountains are there, always, but they transform in all of these ways through the continuum of their lives, what they hold, and the way that water comes down every year and grooves them—like a piercing or a scar or the wrinkles on my face change my own body. I’m very connected to the idea of how short a life I will have, compared to what it is to bear witness to these forms. That’s why I’m making portraits of them. It is so important to remind people that this is significant and there was a time without borders or boundaries. That all of this earth was made, and what we have done as a species to interrupt this. That’s also why images of Norwegian towns and human activity are there, too, to remind you of our own humanness, to control these environments.

CW: A time without borders feels almost impossible to imagine. It reminds me of my older kid, who’s eight now and is learning about history in school. He situates things by looking at the magnolia tree in the backyard. He says, “Is that magnolia tree older than the Civil Rights Movement?” He’s situating his relative understanding of historical time and place in relation to nature. And in doing that, he’s grappling with how old nature is, how cyclical, but also how all the trees around our neighborhood are older than he is. That is a huge psychic change in his little mind.

CO: That’s amazing, because it’s another way of figuring out how to tell time. What is the relationship to time and my being and all of that, and how do I situate myself in this?