Carmen Winant’s Embodied Archives

Artforum / Jun 1, 2025 / by Jessica Simmons-Reid / Go to Original

Carmen Winant, My Birth (detail), 2018, 3,059 found paper and photographic prints, painter’s tape, dimensions variable.

IN APRIL 2018, shortly after becoming a new mother, I made a pilgrimage to see Carmen Winant’s herculean installation My Birth, 2018, at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. The work consists of over three thousand found photographs of women (including the artist’s mother) in various stages of labor and childbirth. It’s a living collage of swollen bellies, crowning heads, bloody sutures, glistening babies, veiny placentas, and ecstatic or exhausted countenances, images that together attempt to apprehend an experience that language itself eludes. While these photographs depict deeply private moments, they were drawn from myriad public sources, including books, magazines, and estate sales. At MoMA, they papered a long and somewhat narrow corridor from floor to ceiling, transforming the gallery space into a veritable birth canal. Visibly secured with torn wedges of blue painter’s tape, a utilitarian material that Winant often employs, the installation ultimately indexed asynchronous forms of touch—the artist’s hand, the mother’s grip, the womb’s constriction, the camera’s shutter—thereby proposing the artwork as both a receptacle for and a reflection of discrete acts of creation.

Carmen Winant, My Birth, 2018, 3,059 found paper and photographic prints, painter’s tape. Installation view, Museum of Modern Art, New York. Photo: Martin Seck.

As I carefully took in My Birth with a close friend, who found herself overwhelmed by the viscerality of the images, an older male security guard remarked to me—someone who has both given birth and attended the birth of another—that “giving birth is a world of pain,” as if corporal suffering were inherently something to be handed overin tandem with the gift of life. Much like birth itself, the human experience of pain is reliably quotidian yet wholly indescribable: Neither words nor images can fully account for the primal, subjective sensations of the body. While questions of pain tend to dominate perceptions of childbirth—how do we numb it, endure it, quantify it?—physical discomfort, whether mild or unrelenting, accounts for only a portion of the experience of birthing a life. As Winant’s installation captured repeatedly, the entire endeavor, which for our species occurs more than 350,000 times per day, involves prolonged periods of waiting and regularly oscillates from the routine to the extreme and back again. In encountering this specific work, I was struck by the palpable tension between the extraordinary nature of the act of birth and the sheer regularity of its occurrence. Thwarting simple conclusions, Winant’s installation reveled in visualizing these contradictions.

Winant, who was born in San Francisco in 1983 and now lives and works in Columbus, Ohio, regularly draws on vernacular photography for her collages, sculptures, mixed-media works, and installations, utilizing this primary source material as a lens for examining feminist histories, the contentious politics of the body, and the phenomenological qualities of the photograph itself. Her focus on the medium’s ability to transcribe and reflect sociopolitical and somatic information, alongside her interest in poetics and her interrogation of the legacies of second-wave feminism, puts her work in dialogue with a feminist tradition of Photoconceptualism that includes figures like Andrea Bowers, Sarah Charlesworth, Moyra Davey, Mary Kelly, Zoe Leonard, and Mierle Laderman Ukeles. Nodding to early works such as Kelly’s Post-Partum Document, 1973–79, which details the often invisible, messy work of motherhood, and Ukeles’s mid-’70s “maintenance work” performances, Winant’s oeuvre approaches her predecessors’ focus on labor and bodily autonomy with an urgency and an inquisitiveness that specifically reflect our contemporaneous political realities.

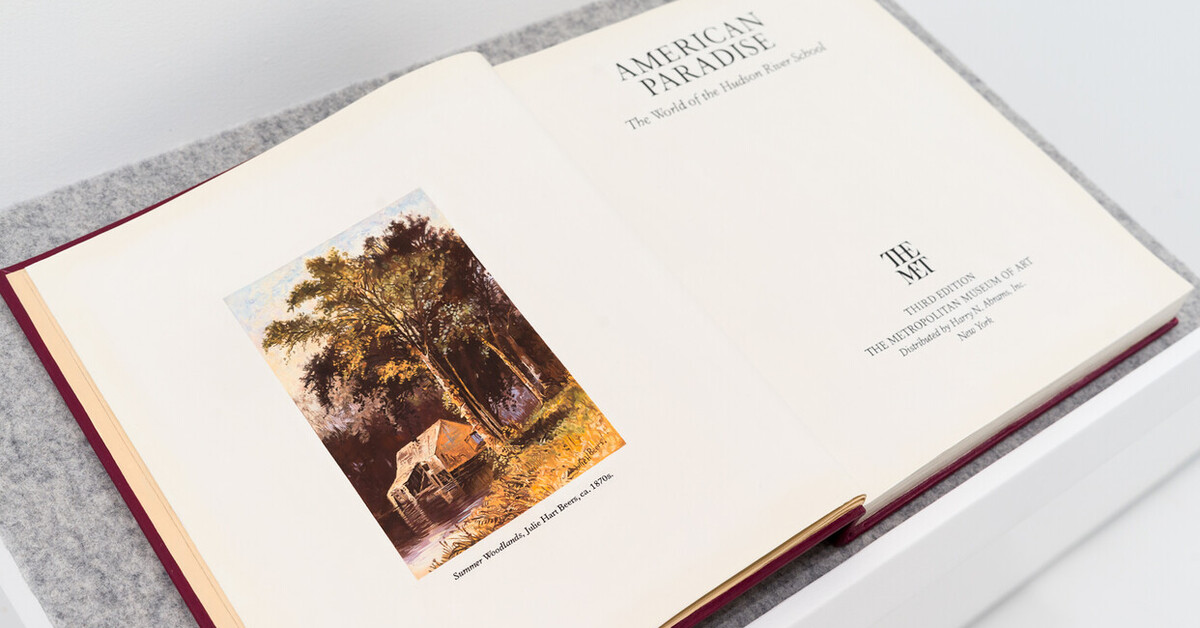

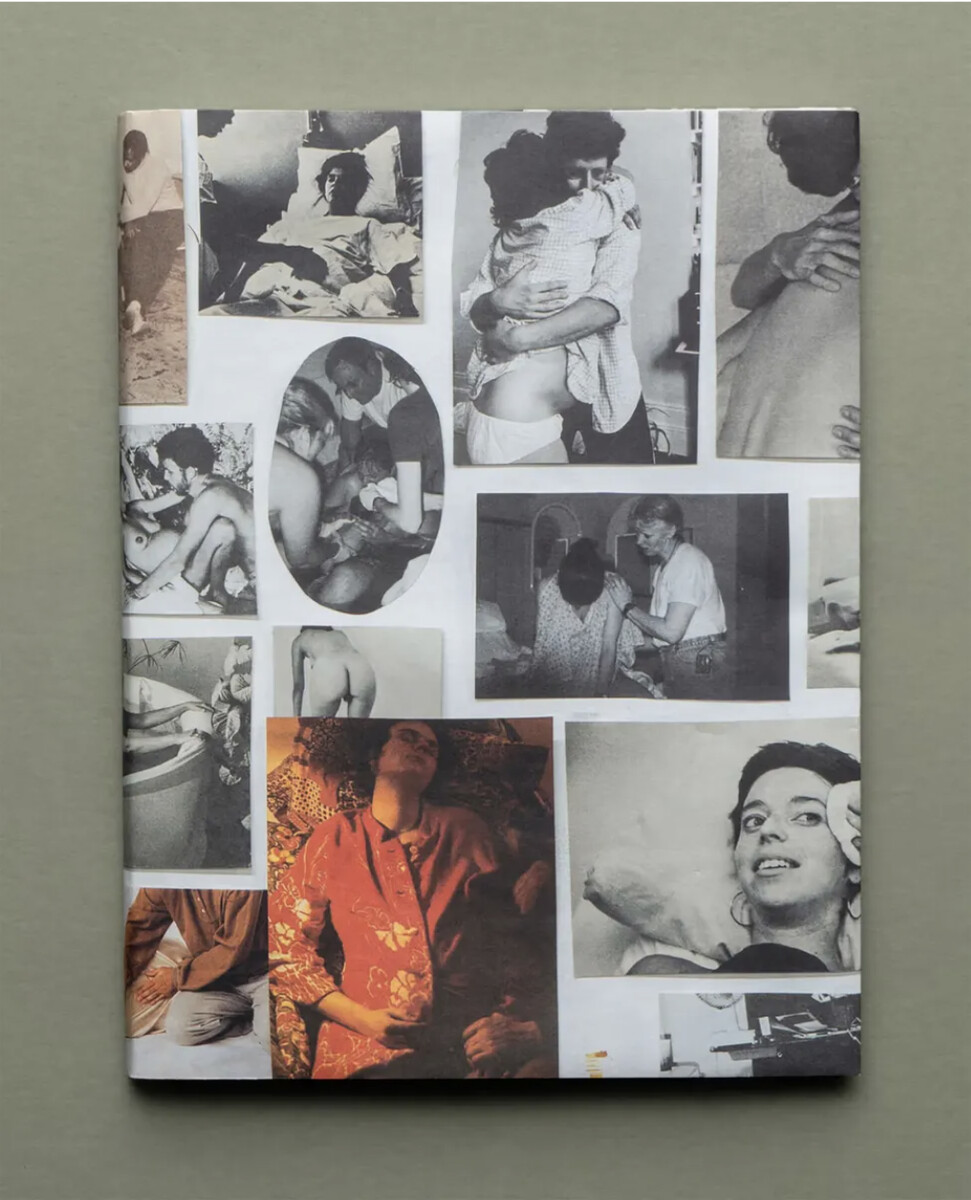

Cover of Carmen Winant’s My Birth (SPBH Editions/MACK, 2018).

She is also a prolific writer, frequently publishing essays and artists’ books that often accompany or complement her physical artworks. For example, while her book My Birth, published in 2018 by SPBH Editions, coincided with the eponymous installation at MoMA, it also served as a stand-alone visual and textual project that further examined the inexplicable nature of childbirth and the futility of attempting to represent it (as well as the dearth of its representation altogether), subjects she first addressed in a 2016 essay for Carla (Contemporary Art Review Los Angeles). She begins the book by posing a series of questions, both practical and philosophical, that address unorthodox topics related to birth, including: “How many instruments were used on your body?,” “Did you look closely at your placenta?,” “Did you have the sense that you were giving birth to yourself?,” and “Did you think of your own mother?” A careful selection of images follows—often just one or two per page—that collectively traces the physiological progression of labor, with tranquil scenes of nude expectant mothers giving way to tense vignettes of clenching bodies and intervening clinicians. While the installation assembles these myriad photographs into a singular tessellated composition, so monumental as to be nearly abstract—its tendency toward this quality underscored by the repeating ready-made geometries of torn tape used to secure the photographs to the wall—the book’s arrangement is more aligned with the rhythm and cadence of poetic meter. Despite its shortcomings, language here convenes with the photograph to become another primary material tasked with confronting the ineffable workings of the body.

About halfway through the book, a short essay punctuates the photographs. This multipage text serves as an interlude, a waypoint between the images that depict labor and the images that depict birth—the moment of fission when one body splits into two. In the delivery process, this in-between state is referred to as the transition phase, marking the beginning of the fetus’s expulsion from the womb and descent into the birth canal. In her text, Winant taps into this tension between singularity and separateness while also grappling with the metaphysical process of becoming (for both child and parent) that childbirth necessarily entails, writing that “in the queerness of giving birth, I also felt that I was being given birth to.” She also writes about being drawn to the specific phrase “a reunion with the body,” which she had underlined in a sentence in a now-forgotten book. This emphasis suggests that through the act of birthing another, a parent acquires a new kind of sentience, imagined here as a freshly inhabited understanding of, and perhaps even a reverence for, the body’s carnal processes. The next images that appear depict three sequential viewpoints, suggesting the frames of a film strip, of a baby’s crowning head. A gloved hand probes the mother, guiding the child’s emergence. Ultimately, if the installation of My Birth functions as a haptic visual mosaic that channels myriad pathways of touch simultaneously, the intimate form of the splayed-open book mirrors the spread legs of this laboring mother—an anomalous subject in art history—whose likeness we graze when turning the page.

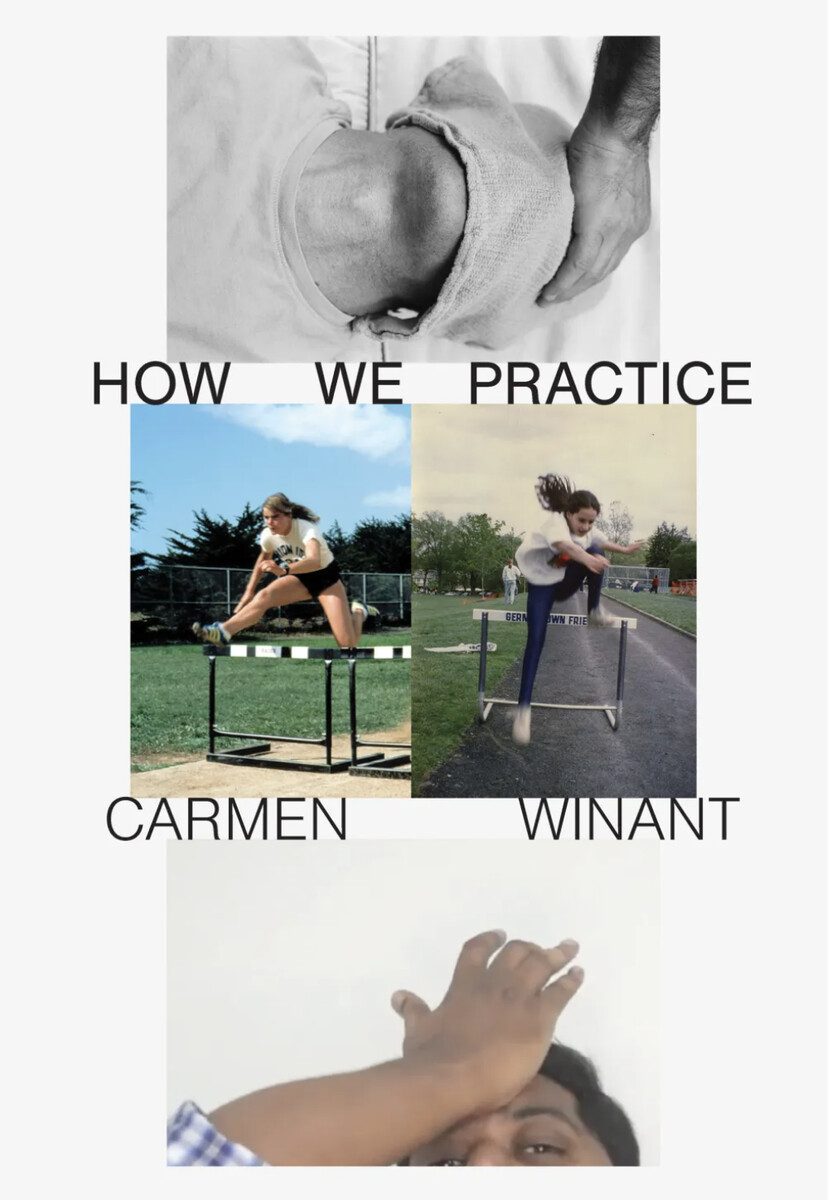

Cover of Carmen Winant’s How We Practice (Dancing Foxes Press, 2025).

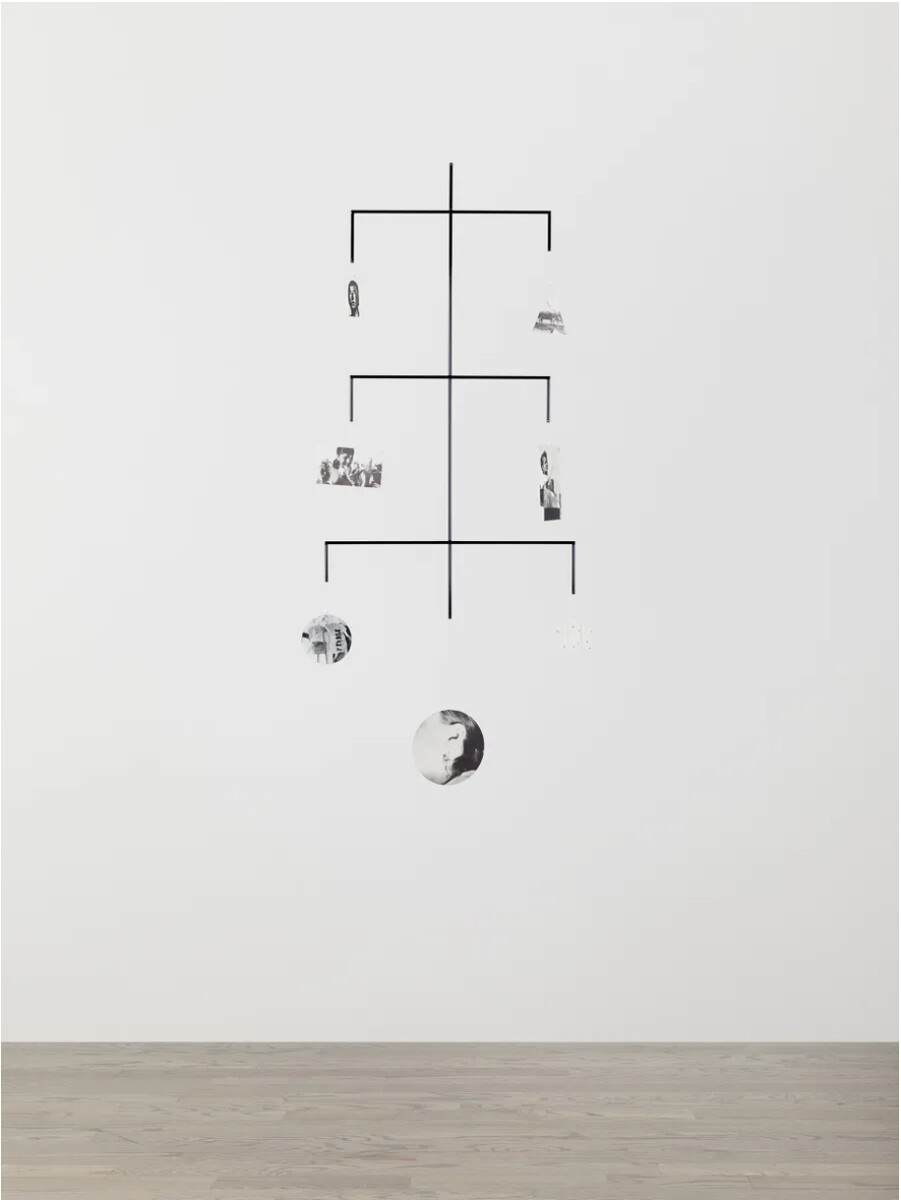

Implicit here is the notion that the act of viewing or taking a photograph can function as a mediated surrogate for the act of touch—a conviction that represents one of the defining conceptual tenets of Winant’s oeuvre. Touch functions as a primal form of knowledge acquisition: To touch something is to attempt to know it and understand it, at least sensuously. By establishing a direct physical tether to the present moment, the act and sense of touch also reinforces intimacy and immediacy. Winant’s artistic impulse to collect and catalogue such highly specific found photographs in projects that all center modalities of touch—including images of abortion clinics (The last safe abortion, 2023), domestic violence survivors (A Brand New End: Survival and Its Pictures, 2022), and lesbian separatist communities (Togethering, 2020)—posits the pre-digital photographic archive as a malleable, living form requiring unique attention and care. She alludes to this idea of an extant physical archive in her 2021 book Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now, which explores the micro-genre of demonstrative imagery by way of found how-to manuals (how to take a Pap smear, how to sculpt a vessel, etc.). “I understand [these images] as constituent parts of a larger body,”she writes, as if there exists a concrete photographic corpus waiting to be plumbed and attended to. Indeed, in stark contrast to the incorporeal nature of a digital image, each of Winant’s photographs is, in a sense, a discrete body: a fallible material entity that boasts a hidden physical history and that will compositionally deteriorate over time. Several of her sculptures, including a series of mobiles exhibited at Patron in Chicago in 2021, enact this allegory of image as body part, reinforcing the concept of an embodied archive. For example, in Portrait of My Spinal Column and Central Nervous System, 2021, a constellation of images extracted from craft manuals—photographs that either directly depict bodily appendages or otherwise allegorize forms of physical contact—are elegantly suspended from a minimalist steel axis, a skeletal scaffold that both supports these photographs and compels them to move. The exhibition’s title, “The Making and Unmaking of the World,” harks back to Winant’s earlier explorations of birth, alluded to here via the form of the nursery mobile in conjunction with other representations of material creation, while also proposing the photographic object as both a vehicle for and index of somatic actualization.

Kineticism, creation, and embodiment: These are all central topics of discussion in Winant’s new book How We Practice, published in May 2025 by Dancing Foxes Press, which is simultaneously a departure from her previous work and a culmination of her theoretical concerns. It is also one of her most personal projects to date. Informed by her life as an artist as well as by her experience as a competitive college athlete (she was a distance runner on the UCLA track team), the book offers an incisive dissection of the word practice, exploring its multifaceted meanings in the seemingly antithetical contexts of artmaking and athletics. While How We Practice isn’t explicitly about photography, it nevertheless contends with photographic concerns, such as the optics of bodily representation and the perpetual tension between the seen and the unseen. In contrast to her book My Birth, Winant’s new volume addresses these topics with very few accompanying images. Here, the word practice, with all its attendant connotations, serves as her primary found material; she pries it open and examines its linguistic essence, finding within it a thick resin of meaning. Reflecting on the nuanced connections between How We Practice and her visual work, Winant told me that the book ultimately offered her “a new proposition … to let go of the writerly impulse to ‘make arguments’ and proceed rather like an artist in the studio: unfolding it as I went, drawing from a kind of muscle memory, [and] experimenting with putting the pieces together.”

Carmen Winant, The last safe abortion (detail), 2024, ink-jet prints, 10′ 6″ × 24′ 6″.

Winant begins the book with what feels like a real-time assessment of her materials, presenting a list of concise definitions that relate to the word practice: an application, a habit, an exercise, a pursuit, a scheme, an expression, a procedure, a premise, an activity, a rehearsal, a policy, a system, a pedagogy, a doctrine, and so on. A series of questions follow, which together illuminate and complicate the meaning of the term, revealing that sometimes language even fails to account for itself. “Can practice be resolved? And if so, does it cease to be practice?” In several cases, she repeats the same question multiple times, swapping in different terms. For example, “Are practice and performance [/absence/theory] dialectical?” “Can there be practice without repetition [/pleasure/suffering/play/submission/bodies]?” The first two essays deconstruct the word practice through the lens of artmaking, with a particular focus on its much-maligned associations with white-collar professionalism (doctors and dentists have practices while artists have studios, as the critique often goes). While critics such as Roberta Smith and Peter Schjeldahl have lambasted its use as a filler word for representing the creative process, Winant offers a more nuanced assessment: “Art,” she reminds us, “is a field without best practices.” Although this may seem to imply that the idea of a practice is fundamentally antithetical to the work of an artist, she argues that the use of this term ultimately correlates with the socioeconomic constraints of our time. “Artists are deferring to practice, often begrudgingly and for all its professionalizing implications, because it best describes the hyperstratified, market-driven world we inherited. To quote the great June Jordan … ‘We must make language accountable to the truths of our experience.’”

For Winant, the truth of her experience places practice in the context of her former athletic pursuits, “where making and feeling is embodied and sensuous.” She defends the intriguing and revelatory assertion that practice, as conceptualized through athletic labor, is more analogous to artmaking than not—both function as psychosomatic endeavors that test endurance and resilience and can be, in their own muddled and contradictory ways, “ecstatic,” “ritualized,” “expectant,” and “unspectacular.” For an athlete, the largely unseen work of practice consumes an immense amount of time and solely exists to support the event of competitive performance, the visible and quantifiable expenditure of skill. This type of endless physical rehearsal, Winant asserts, is reminiscent of artmaking in that it is contingent on productive failure: “Athletic practice reminds us that the breaking down of form, a process of deliberate and regenerative unmaking, is itself a means of production.” Here, the dynamic body becomes a sculptural entity subjected to external forces of pressure, weight, resistance, and tension. Winant notes that this metaphor has been discussed by other artist-athletes such as Kathy Acker and Matthew Barney. Acker, a bodybuilder, reflected on her athletic experience in the 1993 essay “Against Ordinary Language: The Language of the Body,” in which she states that “in a gym”—an arena of and for the body—“language whose purpose is meaning occurs, if at all, only at the edge of its becoming lost.” Birth, pain, touch, artmaking, exercise—all of these sensory experiences seem to trigger the feeling of moving from a space of language to something far beyond it.

Carmen Winant, Portrait of My Spinal Column and Central Nervous System, 2021, found images, automotive paint on steel dowels, powder-coated steel plates, fluorocarbon and tungsten fly fishing beads, 45 × 22 × 7″.

Winant crystallizes this idea of crossing a indescribable threshold through her discussion and analysis of masochism, an intrinsic component of athletic practice that intertwines physical pleasure with pain. She describes this condition not in terms of its textbook definition as a sense of gratification derived from distress, but rather as “a convergence—a repetitive or cyclic rubbing together of pleasure and pain… . Tell me: is there any language on Earth that has a word for this feeling?” Here, she articulates the thesis that the coexistence of pleasure and pain—along with the polar dichotomies of resolution and failure, contraction and expansion, fission and fusion, making and unmaking, practice and performance—hinges on a bodily and linguistic state of in-betweenness underscored by a feeling of perpetual anticipation, a concept she similarly grappled with in her earlier explorations of birth. In this portion of the text, she ultimately lands on a phrase that struck me as epitomizing much of her work as a whole: touching the edge of my body. She writes: “I lived inside of practice for a decade because I craved the feeling of touching the edge of my body. It was at once something to be endured and the yield of that same endurance.” This idea of approaching and interrogating the body’s edge not only aligns with Acker’s idea about tipping across the edge of language, but also directly correlates to the phrase “a reunion with the body” that Winant emphasized in My Birth. Each of these sentiments points to the rich, fertile space that exists at the margins—of the body, of language, of the photograph—while also emphasizing the creative potentialities of touch, the action that propels these often porous edges to meet.

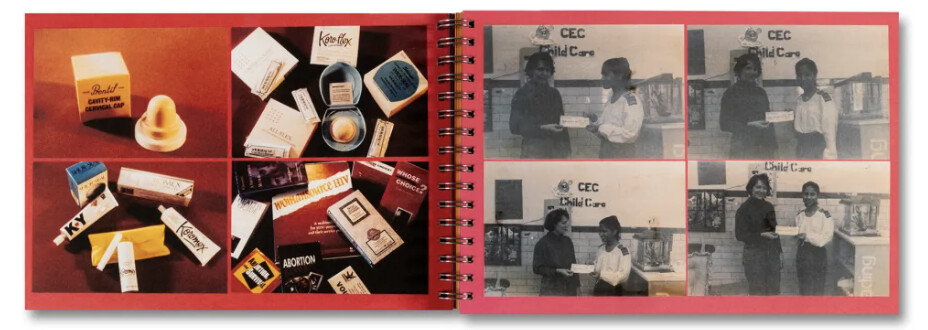

Spread from Carmen Winant’s The Last Safe Abortion (SPBH Editions/MACK, 2024).

Here, a politics of touch emerges: Winant’s focus on defining and catechizing the edge of the body ultimately emphasizes the importance of its sovereignty. The term giving birth subversively supports this: If something isn’t given autonomously and consensually, then it is forcefully and intrusively taken. This subject of bodily autonomy permeates much of Winant’s work and is particularly evident in The last safe abortion, an installation and book project first presented in 2023 that incorporates archival imagery from abortion clinics throughout the United States, documenting the period from 1973, when the Supreme Court codified the constitutional right to abortion in Roe v. Wade, to 2022, when that ruling was overturned. The installation—one of the most memorable works from the 2024 Whitney Biennial—includes over two thousand found images depicting routine abortion care work (photographs of hands shuffling and filing papers, answering phones, drawing blood, conducting ultrasounds), situating its conceit, scope, and scale in direct dialogue with My Birth. Diverging from some of her previous projects, The last safe abortion also includes photographs taken by Winant, who traveled to abortion clinics throughout the Midwest on the eve of Roe v. Wade’s demise. Notably, she includes several self-portraits in this immersive photographic tapestry; the most striking of these images feature her holding the camera, which points directly back at the viewer, offering a striking indictment of the public’s complicity in the failure to protect and uphold reproductive rights. This project highlights an urgent example of how the erosion of corporeal boundaries can become alarmingly dangerous. If authority over the body continues to leach from the private to the public sphere, then access to crucial reproductive health care will be further pushed to the margins of accessibility and allowed to languish there. Here, the edges of the body (and of political reason) are under threat, with lethal consequences. Ultimately, if photography functions as a surrogate for touch, then we can also posit touch as an act of resistance. In The last safe abortion, every instance of touch depicted—from the handling of medical files to the pressure of Winant’s finger on the camera’s shutter—intimately resists, in manners both subtle and overt, the systematic oppression of the body.

Throughout Winant’s work, the politics and poetics of touch frequently branch out and intertwine, often evoking more ephemeral associations. Sometimes the convergence of two distinct boundaries resists and evades touch altogether, such as a horizon line that can never be reached. In How We Practice, Winant invokes this vaporous edge as a symbol of endurance and potential, referring to it as the “space between me and eternity” and as a manifestation of “the art of reaching toward … in perpetuity.” In My Mother and Eye, 2025, a sweeping Public Art Fund project installed in bus shelters across New York City, Boston, and Chicago, eleven discrete photographic collages plumb this intangible meeting point. Situated in transit hubs, the collages interweave film stills from Winant’s mother’s first independent journey as a teenager with photographs from the artist’s own teenage travel expedition, highlighting the horizon line as a metaphorical site of agency and liberation.

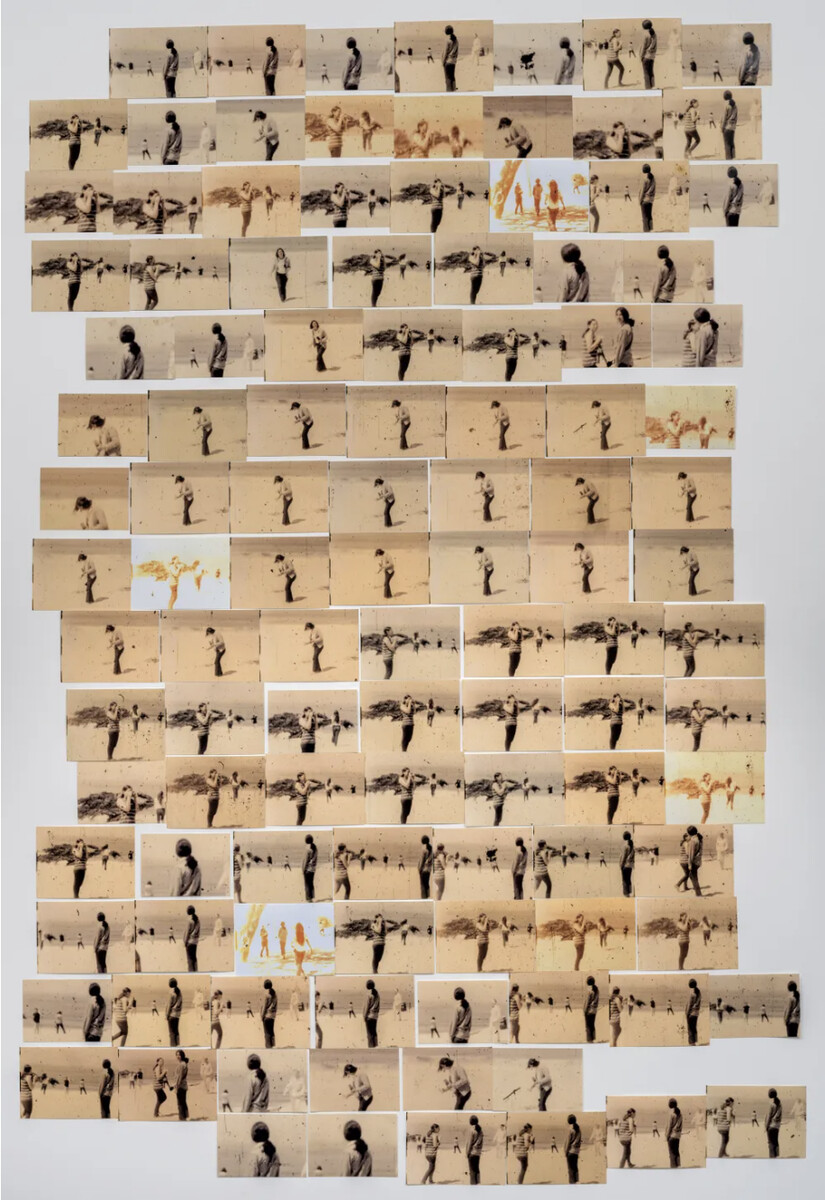

Carmen Winant, Beach (detail), 2024, digital C-print, 68 1⁄2 × 47 1⁄4″. From the project My Mother and Eye, 2025.

The works fold together visual references to the many haptic edges that pepper Winant’s work, including those of the body and the photograph as well as the space between mother and child. Here, the margins of the prints often bleed into one another, disrupting distinctions between past and present, public and private, parent and offspring, and fission and fusion, echoing the dichotomies alluded to in My Birth. These abstract compositions at times appear to coalesce into visual language systems—in Dream, 2024, for example, repeating geometric motifs suggest the formation of glyphs—thereby establishing an intimate dialogue between mother and daughter that transcends delineations of space and time. Just as My Birth attempts to apprehend the transition phase of childbirth, My Mother and Eye delves into the poetics of what we can call the transitory phase, marking the birth of the young adult’s burgeoning self. This project ultimately emphasizes a new articulation of sovereign edges in conjunction with the reunion of two intrinsically connected bodies—a process of becoming once again indexed and embodied by the photograph.