Critic's Pick: Harold Mendez and Ronny Quevedo

Artforum / Sep 26, 2015 / by Andy Campbel / Go to Original

LAWNDALE ART CENTER August 21 2015–September 26 2015

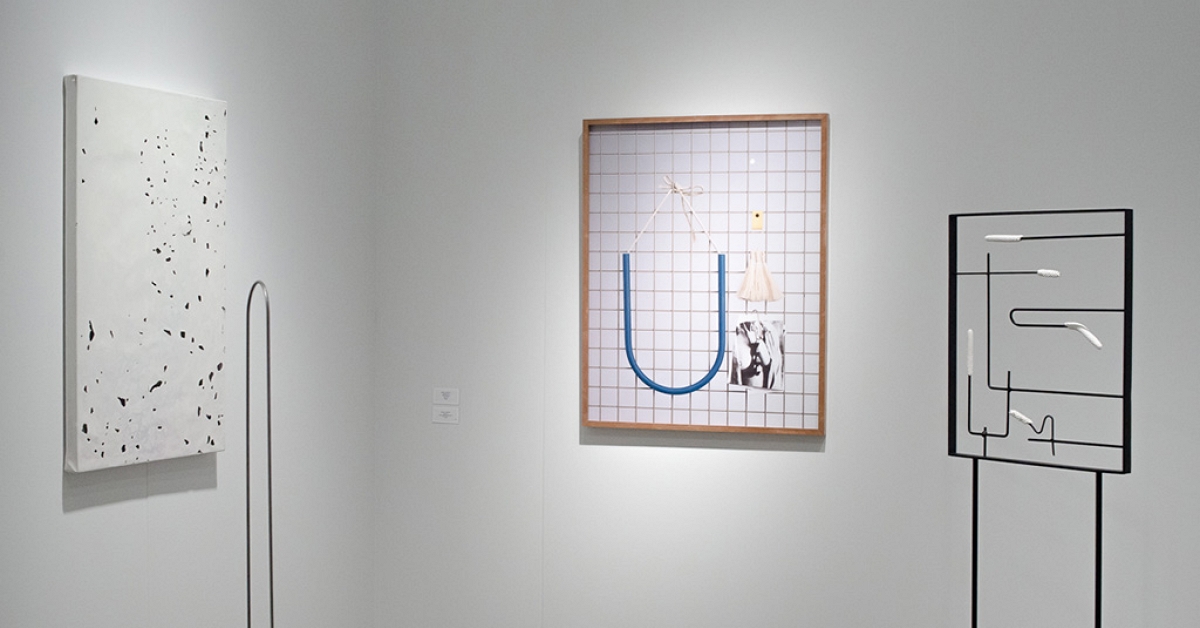

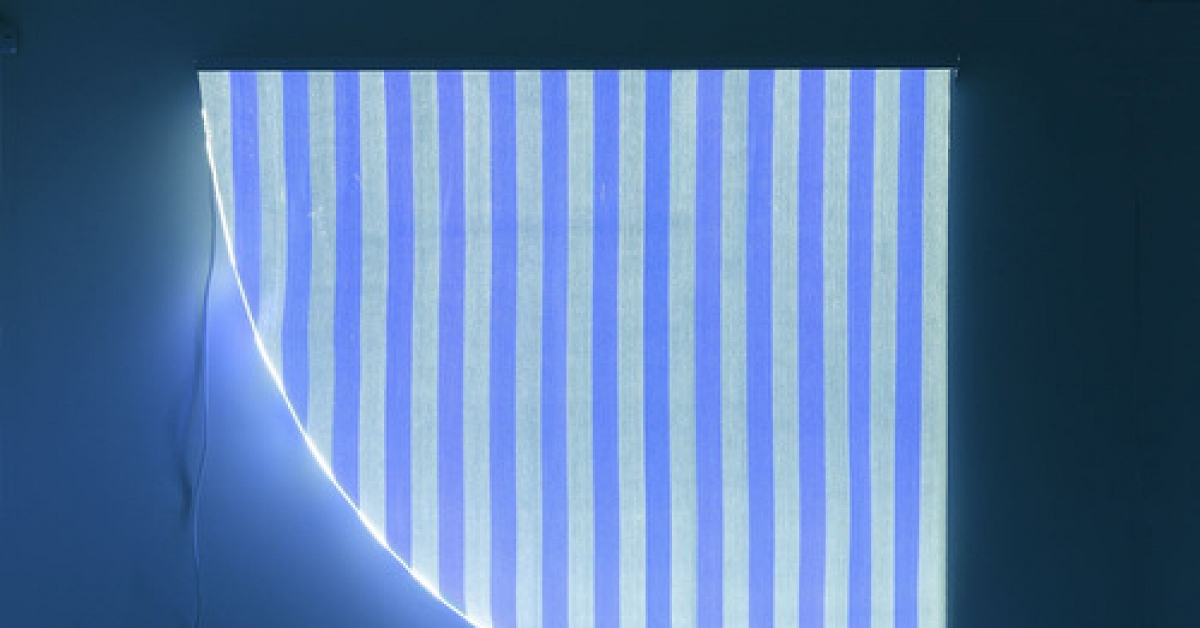

A small copper reproduction of a preColumbian death mask rests inside a burned cardboard box. This tableau is the opening salvo of Harold Mendez and Ronny Quevedo’s collaborative installation, Spector” Field” (all works 2015). That the copper mask sits dumbly at the bottom of its fragile container, unlike the handsome case that holds the gold original at the Museo del Oro in Bogotá, Columbia— is a wry comment on the impulse to preserve precious objects even as the cultures who produced them are systemically smudged out. Mendez and Quevedo’s installation continues in this vein, turning the cavernous central space of Lawndale into a bleak, sparsely populated landscape of diminutive and highly charged sculptural arrangements. Both artists are experts at drawing out connections between materials and their histories. Blue architectural chalk covers a deflated soccer ball, and stadia, both ancient and modern, are covertly invoked. Crushedup cochineal insects coat a trio of cement bags, and elsewhere, shrublike forms sprout out from Lawndale’s black concrete floor. These are small gestures, to be sure, but each asserts itself like an island of a larger archipelago. Quevedo’s Wiphala” on” Broadway, two milk crates whose lattice like structures hold dozens of brightly colored light bulbs, shines out from a high corner. Like everything else here, the sculpture’s associations are specific—the Wiphala is the second flag of Bolivia, its prismatic colors representative of a variety of indigenous peoples—and more generally evocative: a bright sun for a blighted land.

A small copper reproduction of a preColumbian death mask rests inside a burned cardboard box. This tableau is the opening salvo of Harold Mendez and Ronny Quevedo’s collaborative installation, Spector” Field” (all works 2015). That the copper mask sits dumbly at the bottom of its fragile container, unlike the handsome case that holds the gold original at the Museo del Oro in Bogotá, Columbia— is a wry comment on the impulse to preserve precious objects even as the cultures who produced them are systemically smudged out. Mendez and Quevedo’s installation continues in this vein, turning the cavernous central space of Lawndale into a bleak, sparsely populated landscape of diminutive and highly charged sculptural arrangements. Both artists are experts at drawing out connections between materials and their histories. Blue architectural chalk covers a deflated soccer ball, and stadia, both ancient and modern, are covertly invoked. Crushedup cochineal insects coat a trio of cement bags, and elsewhere, shrublike forms sprout out from Lawndale’s black concrete floor. These are small gestures, to be sure, but each asserts itself like an island of a larger archipelago. Quevedo’s Wiphala” on” Broadway, two milk crates whose lattice like structures hold dozens of brightly colored light bulbs, shines out from a high corner. Like everything else here, the sculpture’s associations are specific—the Wiphala is the second flag of Bolivia, its prismatic colors representative of a variety of indigenous peoples—and more generally evocative: a bright sun for a blighted land.