Artists Embrace the Grayscale

Hyperallergic / Jul 20, 2017 / by Sarah Rose Sharp / Go to Original

COLUMBUS, Ohio — The Wexner Center for the Arts is one of those buildings that seems to betray a desire on the part of its creators to force a consideration of the space along with everything on display within it. Largely rejecting the conventional layout of closed-off cubes, the building hosts a string of galleries that feature high-vaulted ceilings, acute angles, and odd segues facilitated by little interior staircases. Running the length of these galleries is a sloping sort of gangway that gradually brings the visitor into the largest exhibition spaces and, combined with glassed-in ceiling and window walls, rather gives one the feeling of being on a cruise ship — especially on an appropriately dark and stormy night like the one that witnessed the opening of Gray Matters, the maiden voyage of newly appointed Senior Curator Michael Goodson.

Goodson chose a simple formal conceit for Gray Matters: It is a group show featuring 37 artists working almost exclusively in shades of gray. Considering that the show was both a rigorous exercise in finding balance among so many monochrome visions, as well as an introduction-by-fire to the unusual gallery spaces newly under his purview, Goodson turned out a dazzling exhibition.

The aesthetics of this show are nearly flawless, with works in wildly disparate media and from very different creators creating extremely satisfying conversations. A long table features ceramicist Arlene Shechet’s stunning 2003 work “Building,” a meditation on the events of September 11th that led the artist to cast a series of vessels in an ash-coated mold, with the inevitable variation in their tone creating a grayscale. The eye follows this work to where it dead-ends into a diptych by Suzanne McClelland, “Rank (Billionaires)” (2017), which seems to float in midair on its invisible mounts. So painterly is Shechet’s touch, and so textural McClelland’s painting, that the transition between the two feels utterly seamless.

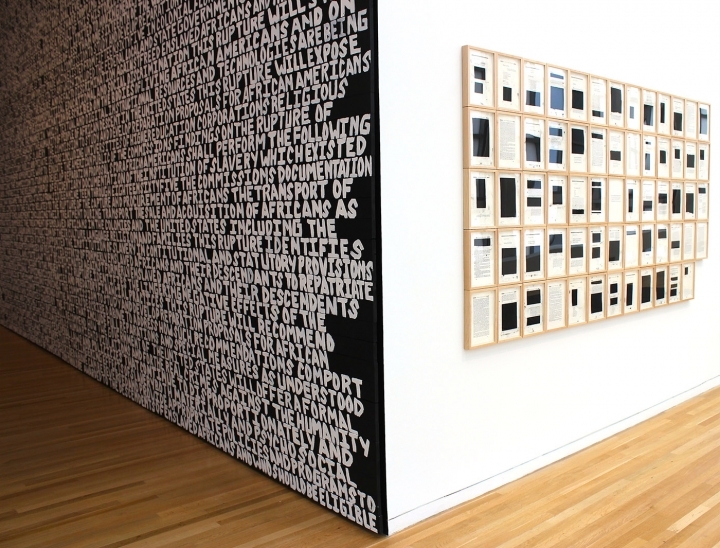

A trio of artists fill another gallery with indecipherable language. Commissioned specially for this exhibition, Xaviera Simmons’s site-specific “Rupture” (2017) dominates an entire wall with the text of a political treatise attempting to raise the question of reparations due to African Americans, with the word “rupture” inserted into the text. The floor-to-ceiling wall of words is nigh unreadable, as is the content of the adjacent works by Bethany Collins that bookend Simmons’s installation. On one side, “A Pattern or Practice” (2015) invisibly renders the language of the US Department of Justice report on the police shooting of Michael Brown, using a blind embossing technique; on the other, “The Southern Review, 1985 (Special Edition)” (2014–15) uses dense fields of black charcoal to redact sections from a special issue of the eponymous literary journal, which consciously featured African American writers. Directly facing Simmons’s piece is Amalia Pica’s “(un)heard” (2016), an entire wall of meticulously mounted “noisemaking objects of protest” that have been literally whitewashed and plastered into silence — thus completing the collection of obstructed and suppressed viewpoints.

Perhaps by now you’ve noticed an additional element of Gray Matters that I’ve intentionally downplayed: Every one of the 37 participating artists is female. It would be a particularly insidious non-compliment to say that it might never occur to the viewer that they were looking at an all-female show; I will say, instead, that it is refreshing to see an all-female lineup in a context that does not feel the need to dramatically emphasize the gender of its participants. Aside from one video work, Mary Reid Kelley’s “This Is Offal” (2015–16), which is tucked away in its own screening room, there are no bodies on display in Gray Matter. This is a show full of incredibly serious ideas, and as a woman prone to having serious ideas of my own, I was extremely moved to experience a show that connected with my internal reality rather than forcing the focus, as always, to the considerations of my bodily form. As Gray Matters handily demonstrates, the life of women is often lived in the mind.

These are merely a few of many strong moments and powerhouse contributors in this show — others include “Totality” (2016) by Katie Paterson, a vertigo-inducing (but nonetheless irresistible) disco ball constructed from the photo negatives of all known footage of eclipses, thrown, in a whirl of reflected lights, onto the walls of a small gallery; “Hair Portrait #20” (2014), an entire wall of Lauryn Hill rendered in grayscale rhinestones by Mickalene Thomas; and the jaw-dropping “Drawing” (2005) by Nancy Rubins, a wall-mounted paper form layered so densely with pencil graphite as to make it almost indistinguishable from a chaotically crushed sheet of lead. Goodson did not pull any punches with his lineup, and neither did the show’s contributors.

One senses that the senior curator also has a sly penchant for double entendre, and perhaps the exhibition’s title refers just as much to the mental life of these artists as to their chosen palette. While Goodson may be inclined to blur black and white in his definitions — and even to break a couple of his own rules, allowing the orange-hot filament center of the 1964 Vija Celmins painting “Heater” to glow its own way — he’s drawn an extremely bold line with his debut at the Wexner. Gray Matters is full of formal delights, aesthetic acrobatics, and a well-balanced monochrome bouquet of incredible artists.

Gray Matters continues at the Wexner Center for the Arts (1871 North High Street,

Columbus) through July 30.