BETHANY JOY COLLINS: UNDERSONG/ PATRON GALLERY

THE SEEN / Nov 30, 2018 / by Amarie Gipson / Go to Original

“Language is the foundation of civilization. It is the glue that holds a people together. It is the first weapon drawn in a conflict.” -Arrival (2016)

In the work of Chicago-based artist Bethany Collins, language is both the subject and material. Language is a prism through which she explores American history and the nuance of racial and national identities. Undersong, her second solo-exhibition at PATRON Gallery, is a journey through lost and unfamiliar lands. The exhibition engages three texts: American patriotic hymns, excerpts from various translations of Homer’s The Odyssey, and classified ads placed by former slaves in search of their loved ones. The three bodies of work in Undersong are linked by an oral tradition. Collins describes the importance of this through line saying, “The Odyssey was passed down orally and the classified ads would be read in church so more people could hear them. The songs only transcend when we sing together, creating this national identity.” Perhaps her most comprehensive exhibition to date, Undersong brings together several signature modes of working that she has developed over the past eight years.

Embodied in her work is the influence of the black church, where captivating storytelling through song and sermon transcends audiences into higher realms. Born and raised in Montgomery, Alabama in the 80s, Collins is avid reader who engages language across time. She is inspired by writers like Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemison, allowing the freedom and possibility in science fiction to feed the way she imagines the world. The texts that make it into her work range from old dictionaries to encyclopedias, literary journals, and most recently epic Western poems. Collins describes these texts “sort of officious, there is a right and wrong being presumed in the authority that we give them. I like to challenge that authority.”

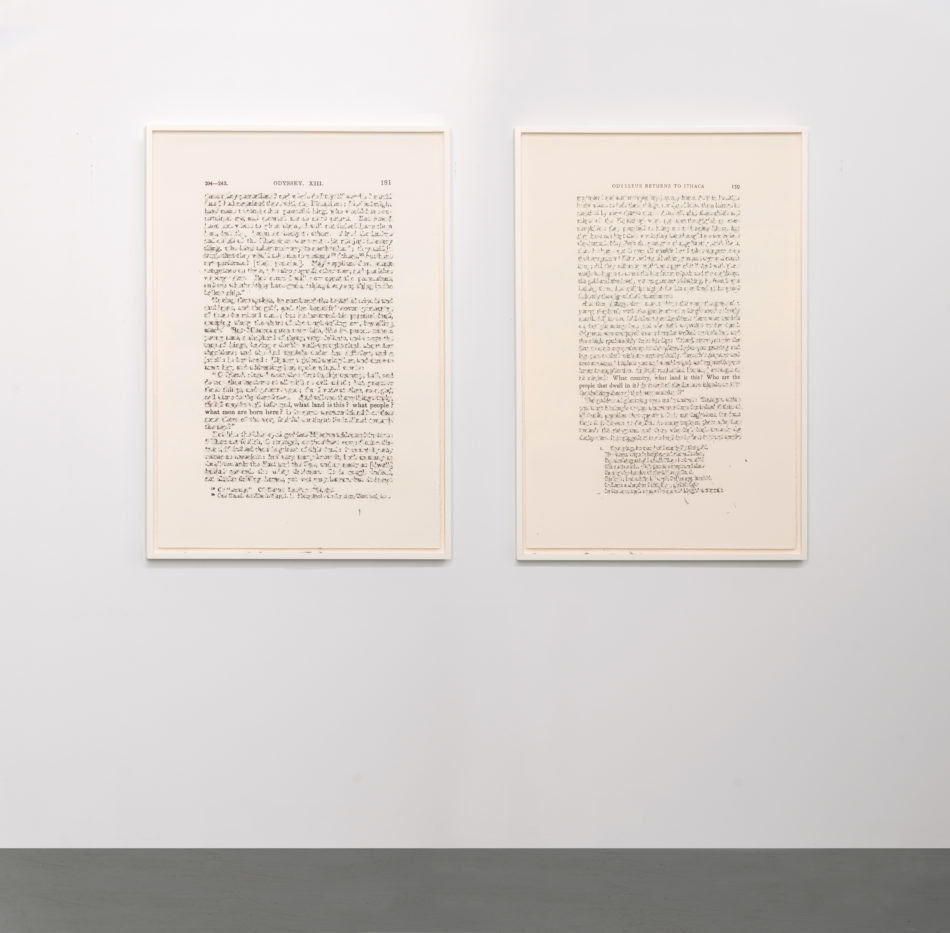

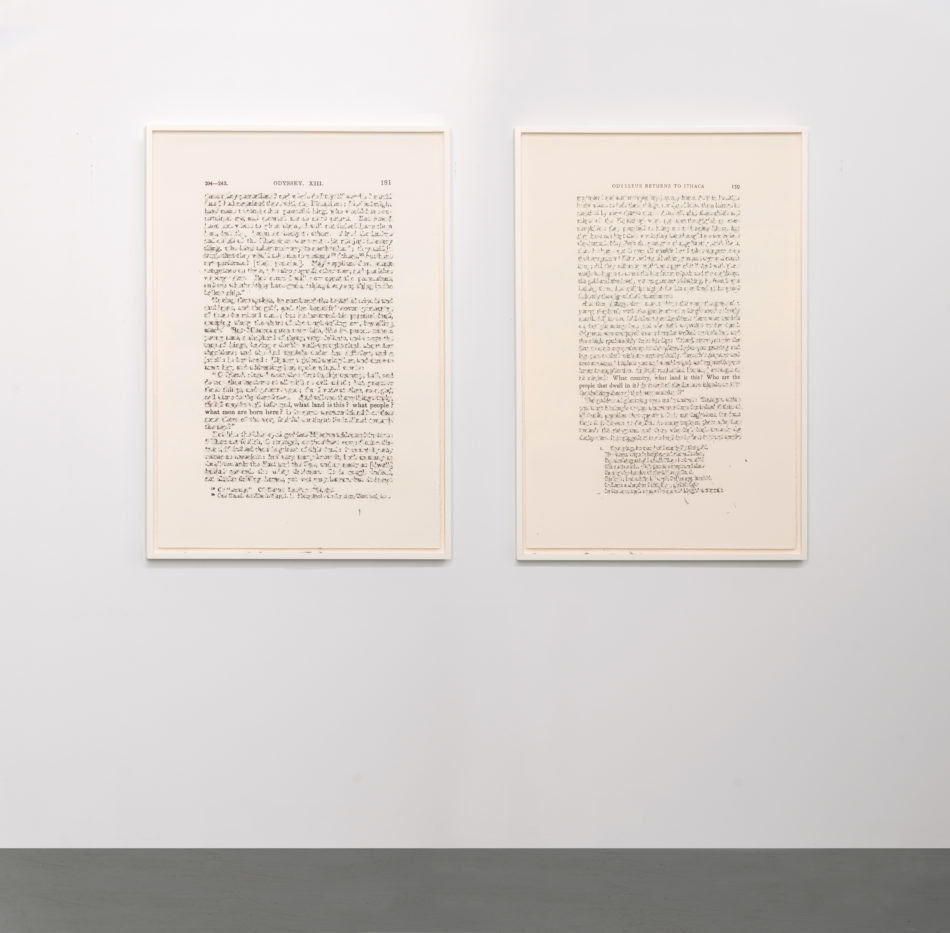

Grounding the exhibition is the Homerian epic. Collins selected pages from the poem to photo transfer onto Somerset paper and paired different translations together. The text is handwritten in graphite then rigorously erased using her saliva, leaving the remains of the paper’s surface inside the frame. In Book 13 of the poem, the protagonist finally returns to his homeland after a long and trying quest, only to find that it has been rendered completely unfamiliar to him. The remains of translations from 1852 and 1980 read, “what land is this? what people? What men are born here” and “What country…Who are the people that dwell in it?” Erasing the surrounding text brings Odysseus’ query into focus. This diptych calls to mind the sense of frustration and unease that has swept across the nation as Americans confront the tragic histories that continue to permeate the present.

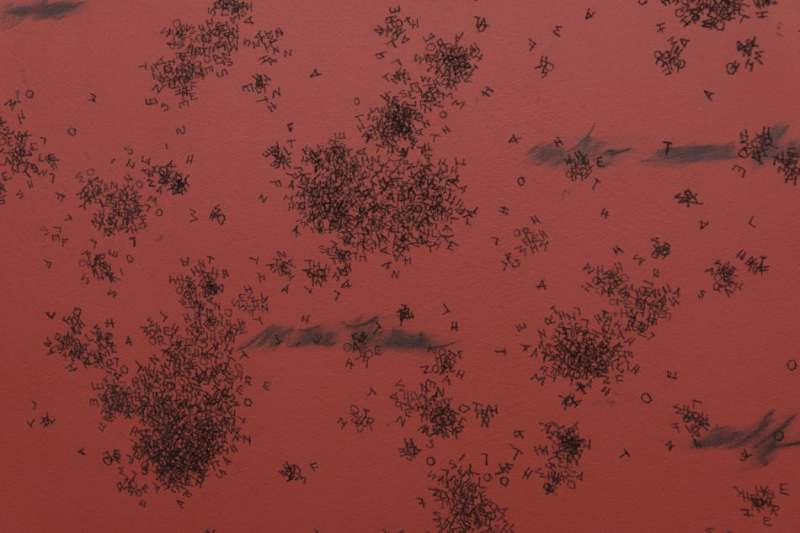

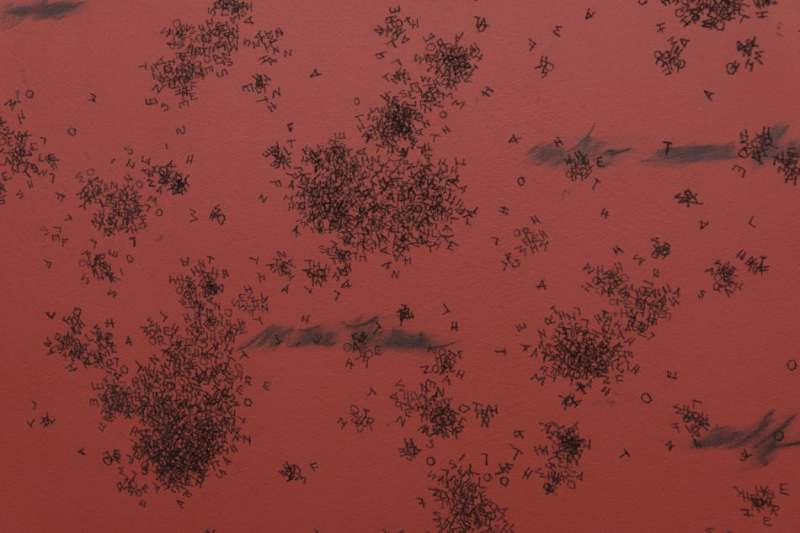

Integral to the making of her work is the use of the body as evidenced in her erasure of historical texts and obsessive repetition of spoken words. Collins continues her exploration of nationhood by obscuring lyrics from American hymnals. The unifying lyrics of patriotic songs such as America The Beautiful and You’re a Grand Old Flag are scrambled and sprawled across panels, rendered in a “write it until you learn it” punishment style. The frantically written lyrics populate a bright red surface, erased and layered until illegible. Pointing to these works in the gallery Collins notes, “Everything has a kind of pain in it. I know the work is valuable when it is somehow painful. It could be abstracted forever, but I know the works are done when my hand hurts and I have to stop the piece.” While the songs attempt to create a unified version of what this country aims to be, their unrecognizable order produces a feeling of disorientation that echoes the tone of the Odyssey works. Perhaps her oldest and most consistent mode of working, this style was derived from her graduate school years in which she took snippets of the microaggressive feedback from her peers and feverishly transcribed it onto chalkboard surfaces in a series called White Noise (2010-2014). This body of work was her first attempt at using and investigating the way violence is embedded in language. In her words, the works are “making noise out of something that should be discernible and legible.” After several years, Collin returns to this cathartic mode of working, placing the focus on the language within the oral legacy of America’s national identity.

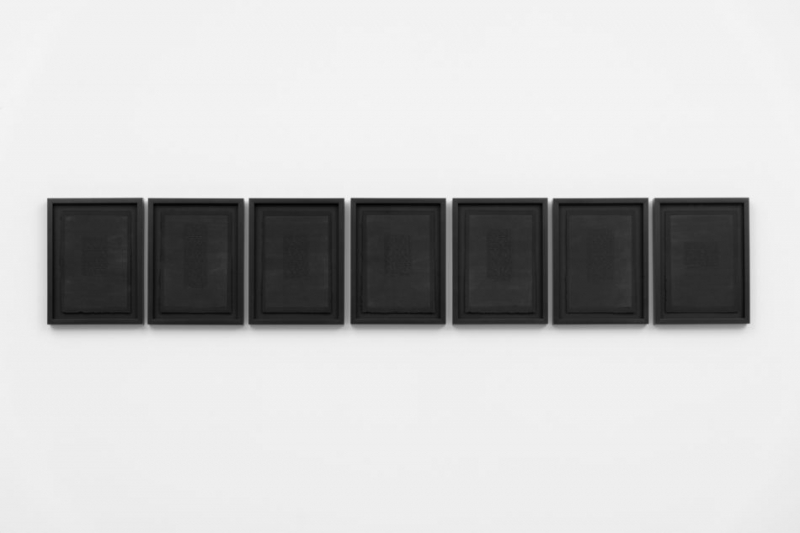

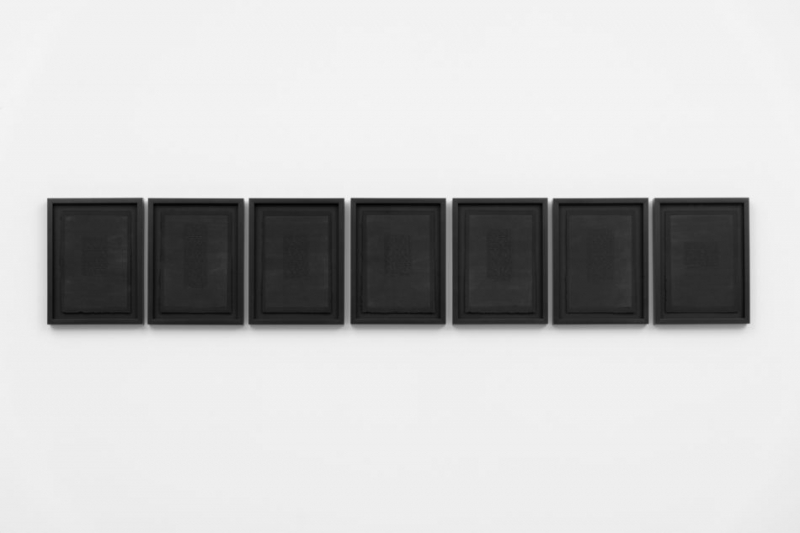

Historical erasure is central to the way that Collins utilizes language. In her blind embossed works, text from classified ads protrude the surface of the paper. Written by former slaves between 1881 and 1898, the ads are a call for any information that would aid them in locating their loved ones displaced throughout the course of slavery in the United States. The text is comprised of bare details: names, physical traits, and brief descriptions of where they originated and where were moved. Phrases like “anxious to hear”, “I belonged to…I was sold”, and “I wish to know” appear within the ads. These remnants of remembrance are characterized by an utter sense of loss. Usually displayed unframed, these works provoke an impulse for the material to be touched. Collins describes that “the embossings are always about a thing that cannot be fully understood or grasped.” For example, Help me find my people, (2018) is a set of seven classified ads printed on black Stonehenge paper. The language within the ads is ridden with grief, a sentiment that Collins treats mournfully by enclosing the prints in black frames. Similarly, the prints in Do you know them, 1898 (2018) are produced on red newsprint that crumbles and falls apart when twice embossed. She came to this mode of working by examining historical publications like The Birmingham News that intentionally buried reportage of the violence happening blocks away from their headquarters throughout the 1960s. Through this twice embossed process, the repetition of history is materialized. The crumpling and tearing are the aftermath of those cycles. How are institutions of suppression maintained, how do they crumble over time, and what (or who) is lost in the process?

The South has informed the way she mines American history through language, forcing us to look deeper into the fabric of the nation to reconsider our binary assumptions of race and identity. She says, “I would not be making this work if I was not from Alabama and had grown up in a biracial family in the heart of the Civil Rights Movement. There’s something utterly American about the Deep South and I think I got the experience that a lot of people are getting in this political moment.” Today, she continues to turn the conversation to the broader American project. Collins forefronts the reality that language is an extension of the people who create it. It is fundamental to the way we understand ourselves and the lands we call our own.

In the work of Chicago-based artist Bethany Collins, language is both the subject and material. Language is a prism through which she explores American history and the nuance of racial and national identities. Undersong, her second solo-exhibition at PATRON Gallery, is a journey through lost and unfamiliar lands. The exhibition engages three texts: American patriotic hymns, excerpts from various translations of Homer’s The Odyssey, and classified ads placed by former slaves in search of their loved ones. The three bodies of work in Undersong are linked by an oral tradition. Collins describes the importance of this through line saying, “The Odyssey was passed down orally and the classified ads would be read in church so more people could hear them. The songs only transcend when we sing together, creating this national identity.” Perhaps her most comprehensive exhibition to date, Undersong brings together several signature modes of working that she has developed over the past eight years.

Embodied in her work is the influence of the black church, where captivating storytelling through song and sermon transcends audiences into higher realms. Born and raised in Montgomery, Alabama in the 80s, Collins is avid reader who engages language across time. She is inspired by writers like Octavia Butler and N.K. Jemison, allowing the freedom and possibility in science fiction to feed the way she imagines the world. The texts that make it into her work range from old dictionaries to encyclopedias, literary journals, and most recently epic Western poems. Collins describes these texts “sort of officious, there is a right and wrong being presumed in the authority that we give them. I like to challenge that authority.”

Grounding the exhibition is the Homerian epic. Collins selected pages from the poem to photo transfer onto Somerset paper and paired different translations together. The text is handwritten in graphite then rigorously erased using her saliva, leaving the remains of the paper’s surface inside the frame. In Book 13 of the poem, the protagonist finally returns to his homeland after a long and trying quest, only to find that it has been rendered completely unfamiliar to him. The remains of translations from 1852 and 1980 read, “what land is this? what people? What men are born here” and “What country…Who are the people that dwell in it?” Erasing the surrounding text brings Odysseus’ query into focus. This diptych calls to mind the sense of frustration and unease that has swept across the nation as Americans confront the tragic histories that continue to permeate the present.

Integral to the making of her work is the use of the body as evidenced in her erasure of historical texts and obsessive repetition of spoken words. Collins continues her exploration of nationhood by obscuring lyrics from American hymnals. The unifying lyrics of patriotic songs such as America The Beautiful and You’re a Grand Old Flag are scrambled and sprawled across panels, rendered in a “write it until you learn it” punishment style. The frantically written lyrics populate a bright red surface, erased and layered until illegible. Pointing to these works in the gallery Collins notes, “Everything has a kind of pain in it. I know the work is valuable when it is somehow painful. It could be abstracted forever, but I know the works are done when my hand hurts and I have to stop the piece.” While the songs attempt to create a unified version of what this country aims to be, their unrecognizable order produces a feeling of disorientation that echoes the tone of the Odyssey works. Perhaps her oldest and most consistent mode of working, this style was derived from her graduate school years in which she took snippets of the microaggressive feedback from her peers and feverishly transcribed it onto chalkboard surfaces in a series called White Noise (2010-2014). This body of work was her first attempt at using and investigating the way violence is embedded in language. In her words, the works are “making noise out of something that should be discernible and legible.” After several years, Collin returns to this cathartic mode of working, placing the focus on the language within the oral legacy of America’s national identity.

Historical erasure is central to the way that Collins utilizes language. In her blind embossed works, text from classified ads protrude the surface of the paper. Written by former slaves between 1881 and 1898, the ads are a call for any information that would aid them in locating their loved ones displaced throughout the course of slavery in the United States. The text is comprised of bare details: names, physical traits, and brief descriptions of where they originated and where were moved. Phrases like “anxious to hear”, “I belonged to…I was sold”, and “I wish to know” appear within the ads. These remnants of remembrance are characterized by an utter sense of loss. Usually displayed unframed, these works provoke an impulse for the material to be touched. Collins describes that “the embossings are always about a thing that cannot be fully understood or grasped.” For example, Help me find my people, (2018) is a set of seven classified ads printed on black Stonehenge paper. The language within the ads is ridden with grief, a sentiment that Collins treats mournfully by enclosing the prints in black frames. Similarly, the prints in Do you know them, 1898 (2018) are produced on red newsprint that crumbles and falls apart when twice embossed. She came to this mode of working by examining historical publications like The Birmingham News that intentionally buried reportage of the violence happening blocks away from their headquarters throughout the 1960s. Through this twice embossed process, the repetition of history is materialized. The crumpling and tearing are the aftermath of those cycles. How are institutions of suppression maintained, how do they crumble over time, and what (or who) is lost in the process?

The South has informed the way she mines American history through language, forcing us to look deeper into the fabric of the nation to reconsider our binary assumptions of race and identity. She says, “I would not be making this work if I was not from Alabama and had grown up in a biracial family in the heart of the Civil Rights Movement. There’s something utterly American about the Deep South and I think I got the experience that a lot of people are getting in this political moment.” Today, she continues to turn the conversation to the broader American project. Collins forefronts the reality that language is an extension of the people who create it. It is fundamental to the way we understand ourselves and the lands we call our own.