Review: Bethany Collins, Undersong

Artforum / Dec 1, 2018 / by Brian T. Leahy / Go to Original

“I’ve been told that my mother’s name was Millie.” So wrote Lula Montgomery in an 1898 newspaper ad filled with half-remembered names, which Montgomery paid for in hopes that a reader might reconnect her with the family she lost when she was sold, as a baby, into the hands of a different slave owner in Richmond, Virginia. Adopting the heading of this ad for the work Do You Know Them? (1898), 2018, Bethany Collins embossed Montgomery’s words twice over on a fragile sheet of crimson newsprint, resurrecting their haunting refrain; the other nine sheets that comprise this work echo the words written by other men and women who had also been separated from their families.

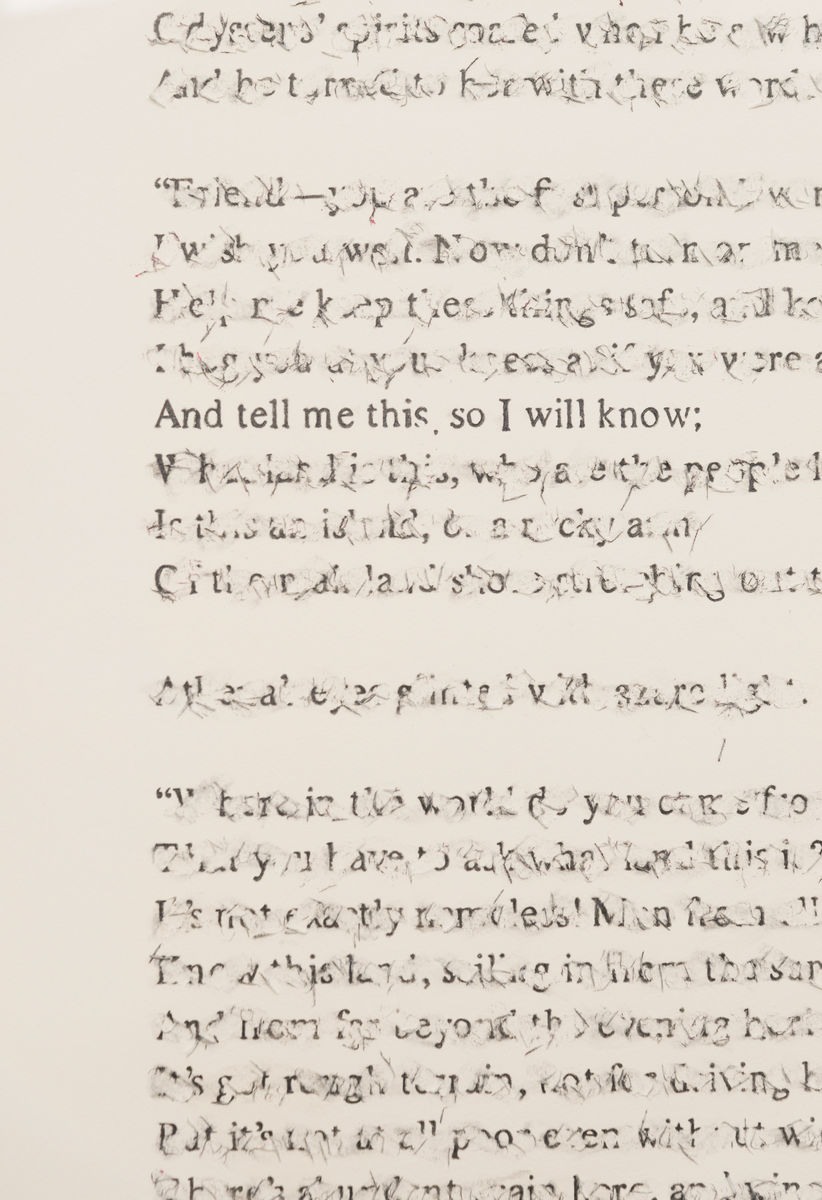

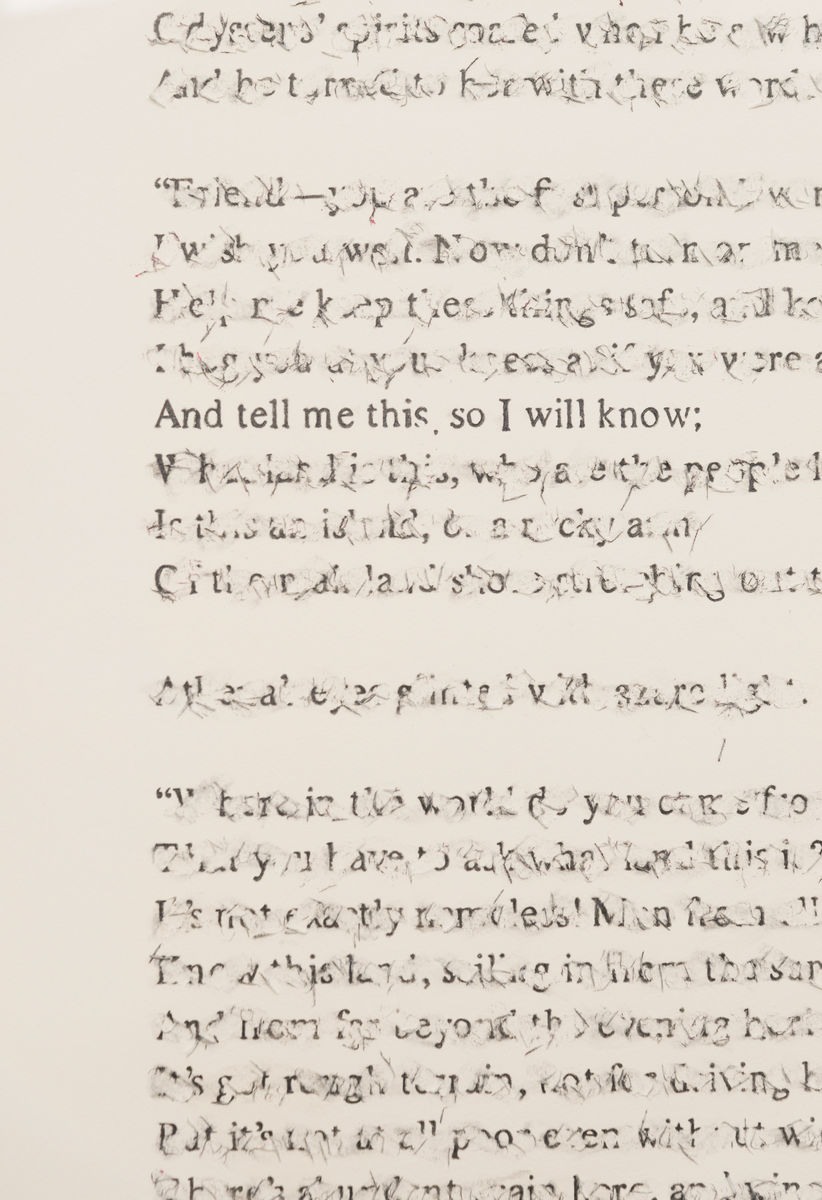

For Collins’s solo show at Patron, the newsprint represented one of three techniques that the artist has previously used to manipulate text. Help me to find my people, 2018, which aligned with Do You Know Them? (1898), consisted of similar classifieds blind-embossed onto black paper; “I wish to inquire for my people” was a typical opening line, difficult to discern against the text’s identically tinted ground. A trio of large panels layered with a skin of cranberry-colored latex paint provided fields over which Collins repetitively transcribed lyrics from patriotic hymns such as “America the Beautiful” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” extracting ambiguous evocations of love and homeland from shopworn tunes. In a final strategy that contrasted with the small scale of the newsprint pleas, Collins rendered selections from Homer’s Odyssey in graphite on large white sheets of paper.

This last body of work was sourced from single pages of different translations of Homer’s epic, which Collins meticulously replicated in dark-gray characters only to subject them to erasure with a mixture of Pink Pearl erasers and her own saliva; remnants of the process dust the bottom of the frames’ interiors. In tempering the text in this way, the artist was able to employ editorial precision: Within each diptych or triptych in the series, Collins left a brief snippet of text legible across the distinct translations. These phrases—each from the passage in which Odysseus, abandoned onshore, fails to recognize his erstwhile homeland—distilled the disorienting homesickness of the tale and rhymed with the ache for a missing family expressed by Montgomery and other former slaves in their printed testimonials.

Collins’s investigations of the ways in which race, identity, and history are bound by language could easily lend themselves to well-worn interpretive ruts. But what each work courted, at the edges of its formal and conceptual fastidiousness, was the materiality of language itself. Language matters for Collins in the doubled sense articulated by feminist physicist-theorist Karen Barad: It is both substantial and signifying. Words can and do reform our material realities. For example, dictionaries—key objects in earlier works by the artist, including Colorblind Dictionary, 2015, a found Merriam-Webster volume from which Collins erased all terms relating to color—accrete racialized language that codifies hegemonic colonial power. But this understanding of language as a site of political and historical struggle leads to works that foreground textual counterpractices—those that do not shirk from describing violence yet also employ language as a tool for dismantling larger systems, resisting the assumption that language need always serve those in power. Collins repeatedly asks (to use the exposed terms of one translation of The Odyssey), “Please tell me the nature of things around here / so I may judge for myself what I have fallen into.” And so that, Collins might add, I may do something about it.

— Brian T. Leahy

For Collins’s solo show at Patron, the newsprint represented one of three techniques that the artist has previously used to manipulate text. Help me to find my people, 2018, which aligned with Do You Know Them? (1898), consisted of similar classifieds blind-embossed onto black paper; “I wish to inquire for my people” was a typical opening line, difficult to discern against the text’s identically tinted ground. A trio of large panels layered with a skin of cranberry-colored latex paint provided fields over which Collins repetitively transcribed lyrics from patriotic hymns such as “America the Beautiful” and “You’re a Grand Old Flag,” extracting ambiguous evocations of love and homeland from shopworn tunes. In a final strategy that contrasted with the small scale of the newsprint pleas, Collins rendered selections from Homer’s Odyssey in graphite on large white sheets of paper.

This last body of work was sourced from single pages of different translations of Homer’s epic, which Collins meticulously replicated in dark-gray characters only to subject them to erasure with a mixture of Pink Pearl erasers and her own saliva; remnants of the process dust the bottom of the frames’ interiors. In tempering the text in this way, the artist was able to employ editorial precision: Within each diptych or triptych in the series, Collins left a brief snippet of text legible across the distinct translations. These phrases—each from the passage in which Odysseus, abandoned onshore, fails to recognize his erstwhile homeland—distilled the disorienting homesickness of the tale and rhymed with the ache for a missing family expressed by Montgomery and other former slaves in their printed testimonials.

Collins’s investigations of the ways in which race, identity, and history are bound by language could easily lend themselves to well-worn interpretive ruts. But what each work courted, at the edges of its formal and conceptual fastidiousness, was the materiality of language itself. Language matters for Collins in the doubled sense articulated by feminist physicist-theorist Karen Barad: It is both substantial and signifying. Words can and do reform our material realities. For example, dictionaries—key objects in earlier works by the artist, including Colorblind Dictionary, 2015, a found Merriam-Webster volume from which Collins erased all terms relating to color—accrete racialized language that codifies hegemonic colonial power. But this understanding of language as a site of political and historical struggle leads to works that foreground textual counterpractices—those that do not shirk from describing violence yet also employ language as a tool for dismantling larger systems, resisting the assumption that language need always serve those in power. Collins repeatedly asks (to use the exposed terms of one translation of The Odyssey), “Please tell me the nature of things around here / so I may judge for myself what I have fallen into.” And so that, Collins might add, I may do something about it.

— Brian T. Leahy