NXTHVN Breaks Down The Myths

New Haven Independent / Mar 11, 2020 / by Brian Slattery / Go to Original

In a studio somewhere, artist Jarrett Key stands in front of a blank canvas. Their hair is tied up in the shape of a brush. Without a word, they dip their hair into a small bucket of paint, then back up to the canvas behind them. They tilt their head back and begin to paint, without really being able to see what’s behind them.

It can feel trite to say that the process of creating a piece of art is part of the artwork, but Key’s movements are so balletic that in this case, the statement feels true. Understanding how the paintings were made gives more meaning to the finished paintings.

Key’s work is part of “Countermythologies,” the first exhibition at NXTHVN, the gallery, studio, co-work space, theater, and cafeopening on the site of a former factory on Henry Street in Dixwell.

The exhibition celebrated its opening on Saturday, with the exhibition installed until May 10. While work continues on the other aspects of the space, the exhibit represents the first chance for the public to see how the space has been transformed, and what direction the organization is headed in artistically.

Like much art these days, “Countermythologies” — curated by Zalika Azim, Riham Majeed, and Ana Tuazon — is overtly political. “The artworks of eight artists build a different model of historical consciousness, illuminating the interwovenness of the past with the present, and the personal with the collection,” states an accompanying note. “Engaging with subjects like the afterlife of slavery, the sharing of stolen land, and language as a tool of imperialism, these works challenge the myth of U.S. national identity and belonging that promises ‘liberty and justice for all,’ as it fails to deliver these for most citizens. Through stories, provocations, and laments, the exhibition offers alternative understandings of what American ‘belonging’ could look and sound like.” To conclude, the note states, the exhibition “proposes that when the narratives we tell about ourselves change, so will the futures we are able to envision.”

The description of Key’s work tells us that the artist invoked stories their grandmother told them about Samson and Delilah when making the paintings, which explains the use of the hair. Almost more important than the specific evocation, however, is the general method Key used to create the paintings. They cast aside the conventional ways of painting — ways mostly handed to us by European forbears, working within a Western European tradition — and instead reached into their own family history to find a new way to make art.

Sky Hopinka’s short filmVisions of an Island,meanwhile, is nearly a documentary; through it we gain a new appreciation of the islands in the Bering Sea. Maybe we think of them as the far hinterlands of the United States, a distant outpost from the capital. Hopinka’s film reveals that to the Unangam Tunuu who have lived there, and lived off the land, for generations, the islands are the center; we’re the distant power.

Hitting closer to home in Connecticut, Xaviera Simmons’s work first calls attention to the legacies of sundown towns — places that, as the accompanying note says, “did not welcome Black Americans after dark.” In mixing past and present, Simmons reminds us that we haven’t moved as far from many overtly racist laws of the past as we might like to believe. One era’s sundown law is another era’s redlining, is yet another era’s fight over where to put new public housing.

Meanwhile, another of Simmons’s pieces dominates the back wall of the gallery. “Drawing inspiration from the traditions of jazz composition, Simmons uses improvisation to construct a series of breaks, repetition, and sequencing in her re/telling of the narrative she has selected,” the accompanying note explains. The link to music is helpful, as Simmons’s placement of the text defies an attempt to read it as a linear text. Understanding it as possible parallel narratives that can be combined and recombined suggests the possibility of finding new ways of reading, and by extension new ways to construct meaning.

Edgar Arceneaux’s works unearth a moment when culture began a lightning rod — when actor and dancer Ben Vereen,in an homage to black vaudevillian Bert Williams, performed a routine in blackface for Ronald Reagan’s inaugural ball in 1981. The full performance, and particularly the second half, was intended to make its immediate white audience uncomfortable, making them complicit in perpetuating a racist system. Unfortunately, television networks refused to air the second half, meaning that African Americans only saw the first half of Vereen’s routine, which didn’t make clear what he was doing. The resulting anger and confusion damaged Vereen’s career. Like Simmons’s work, Arceneaux’s piece — consisting of artifacts of a time Arceneaux restaged the piece as performance art, adding another layer to the episode — makes clear just how potent images of blackface still are, and just how little we’ve moved away from the racism in the past we sometimes like to think is far behind us. The shock it delivers is earned.

Bethany Collins, Do You Know Them? (1897)

One of Bethany Collins’s pieces focuses on classified ads run in the African-American-run newspaperThe Richmond Planetin 1897. Each ad was titled “do you know them?” and was an attempt by the person who placed the ad to find family members separated during slavery. The blood-red color of each ad connotes both the ties that bound the seeker to the sought, and the wound left by the family’s absence.

Firelei Báez’s work, likewise, reminds us of the humanity of the people enslaved to work on sugar plantations in the Caribbean.

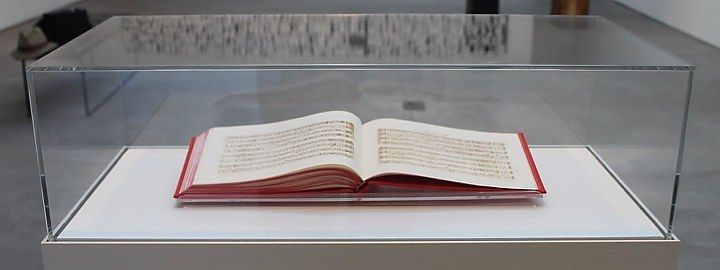

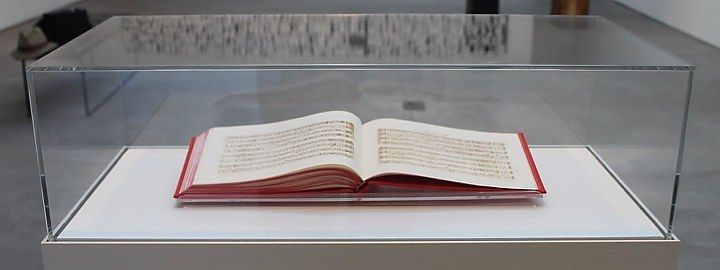

Bethany Collins, America: A Hymnal

But in the context of the exhibit, there is a point to this hard reckoning with America’s past, a point to tearing down the comfortable myths our country tells to itself. Just as previous pieces point to new perspectives about power, new ways of constructing meaning, Bethany Collins’s hymnal rewrites “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” a hundred times over. Perhaps a new anthem can be made from the parts of the old, to include everyone who lives here now.

The exhibit thus lends weight to a neon piece in the lobby that might seem a little glib when you first walk in, but gathers weight to become a more powerful message after you’ve seen the rest of the exhibit and are walking out. It’s a good note for NXTHVN to begin on, as it opens its doors to its immediate neighbors on Henry Street, to Dixwell, and to the greater New Haven community.

It can feel trite to say that the process of creating a piece of art is part of the artwork, but Key’s movements are so balletic that in this case, the statement feels true. Understanding how the paintings were made gives more meaning to the finished paintings.

Key’s work is part of “Countermythologies,” the first exhibition at NXTHVN, the gallery, studio, co-work space, theater, and cafeopening on the site of a former factory on Henry Street in Dixwell.

The exhibition celebrated its opening on Saturday, with the exhibition installed until May 10. While work continues on the other aspects of the space, the exhibit represents the first chance for the public to see how the space has been transformed, and what direction the organization is headed in artistically.

Like much art these days, “Countermythologies” — curated by Zalika Azim, Riham Majeed, and Ana Tuazon — is overtly political. “The artworks of eight artists build a different model of historical consciousness, illuminating the interwovenness of the past with the present, and the personal with the collection,” states an accompanying note. “Engaging with subjects like the afterlife of slavery, the sharing of stolen land, and language as a tool of imperialism, these works challenge the myth of U.S. national identity and belonging that promises ‘liberty and justice for all,’ as it fails to deliver these for most citizens. Through stories, provocations, and laments, the exhibition offers alternative understandings of what American ‘belonging’ could look and sound like.” To conclude, the note states, the exhibition “proposes that when the narratives we tell about ourselves change, so will the futures we are able to envision.”

The description of Key’s work tells us that the artist invoked stories their grandmother told them about Samson and Delilah when making the paintings, which explains the use of the hair. Almost more important than the specific evocation, however, is the general method Key used to create the paintings. They cast aside the conventional ways of painting — ways mostly handed to us by European forbears, working within a Western European tradition — and instead reached into their own family history to find a new way to make art.

Sky Hopinka’s short filmVisions of an Island,meanwhile, is nearly a documentary; through it we gain a new appreciation of the islands in the Bering Sea. Maybe we think of them as the far hinterlands of the United States, a distant outpost from the capital. Hopinka’s film reveals that to the Unangam Tunuu who have lived there, and lived off the land, for generations, the islands are the center; we’re the distant power.

Hitting closer to home in Connecticut, Xaviera Simmons’s work first calls attention to the legacies of sundown towns — places that, as the accompanying note says, “did not welcome Black Americans after dark.” In mixing past and present, Simmons reminds us that we haven’t moved as far from many overtly racist laws of the past as we might like to believe. One era’s sundown law is another era’s redlining, is yet another era’s fight over where to put new public housing.

Meanwhile, another of Simmons’s pieces dominates the back wall of the gallery. “Drawing inspiration from the traditions of jazz composition, Simmons uses improvisation to construct a series of breaks, repetition, and sequencing in her re/telling of the narrative she has selected,” the accompanying note explains. The link to music is helpful, as Simmons’s placement of the text defies an attempt to read it as a linear text. Understanding it as possible parallel narratives that can be combined and recombined suggests the possibility of finding new ways of reading, and by extension new ways to construct meaning.

Edgar Arceneaux’s works unearth a moment when culture began a lightning rod — when actor and dancer Ben Vereen,in an homage to black vaudevillian Bert Williams, performed a routine in blackface for Ronald Reagan’s inaugural ball in 1981. The full performance, and particularly the second half, was intended to make its immediate white audience uncomfortable, making them complicit in perpetuating a racist system. Unfortunately, television networks refused to air the second half, meaning that African Americans only saw the first half of Vereen’s routine, which didn’t make clear what he was doing. The resulting anger and confusion damaged Vereen’s career. Like Simmons’s work, Arceneaux’s piece — consisting of artifacts of a time Arceneaux restaged the piece as performance art, adding another layer to the episode — makes clear just how potent images of blackface still are, and just how little we’ve moved away from the racism in the past we sometimes like to think is far behind us. The shock it delivers is earned.

Bethany Collins, Do You Know Them? (1897)

One of Bethany Collins’s pieces focuses on classified ads run in the African-American-run newspaperThe Richmond Planetin 1897. Each ad was titled “do you know them?” and was an attempt by the person who placed the ad to find family members separated during slavery. The blood-red color of each ad connotes both the ties that bound the seeker to the sought, and the wound left by the family’s absence.

Firelei Báez’s work, likewise, reminds us of the humanity of the people enslaved to work on sugar plantations in the Caribbean.

Bethany Collins, America: A Hymnal

But in the context of the exhibit, there is a point to this hard reckoning with America’s past, a point to tearing down the comfortable myths our country tells to itself. Just as previous pieces point to new perspectives about power, new ways of constructing meaning, Bethany Collins’s hymnal rewrites “My Country ‘Tis of Thee” a hundred times over. Perhaps a new anthem can be made from the parts of the old, to include everyone who lives here now.

The exhibit thus lends weight to a neon piece in the lobby that might seem a little glib when you first walk in, but gathers weight to become a more powerful message after you’ve seen the rest of the exhibit and are walking out. It’s a good note for NXTHVN to begin on, as it opens its doors to its immediate neighbors on Henry Street, to Dixwell, and to the greater New Haven community.