O say can you see, what 100 versions of the Star-Spangled Banner reveal about America

The Art Newspaper / Jun 8, 2021 / by Margaret Carrigan / Go to Original

Bethany Collins in studio, Photography by Chris Edward

The insurrection, which left five people dead and around 150 injured, was a blatant attack on American democracy. But it was the very emblem of that ideal—the American flag—that the mob carried more than any other that day, calling upon its stars and stripes for validation of their violence while further dividing the nation.

Violence, however, is deeply woven into the US flag’s complicated and contested symbology, as the US artist Bethany Collins explores in her new series of works titled The Star Spangled Banner. Each of the three charcoal and acrylic paintings in the series contains a lyric from an alternate version of the national anthem,The Star-Spangled Banner, first penned by Francis Scott Key as a paean to the US flag in 1814. Lines such as “And the glory of death—for the Stripes and the Stars” and “Til the pen, or the orator, stirs them to fight” (also the titles of the corresponding paintings in the series) “romanticise violence in support of patriotic duty”, Collins says.

Moreover, the artist dredges up overlooked and forgotten lyrics from different versions of the song, such as, “Where the lash is made red in the blood of the slave”, which valorises racial violence and white supremacy. In its many variations, the work in the show can be seen as a retelling of American history through one song, which advocates for a specific if not contradictory version of “Americanness” based on who is singing it, according to Collins.

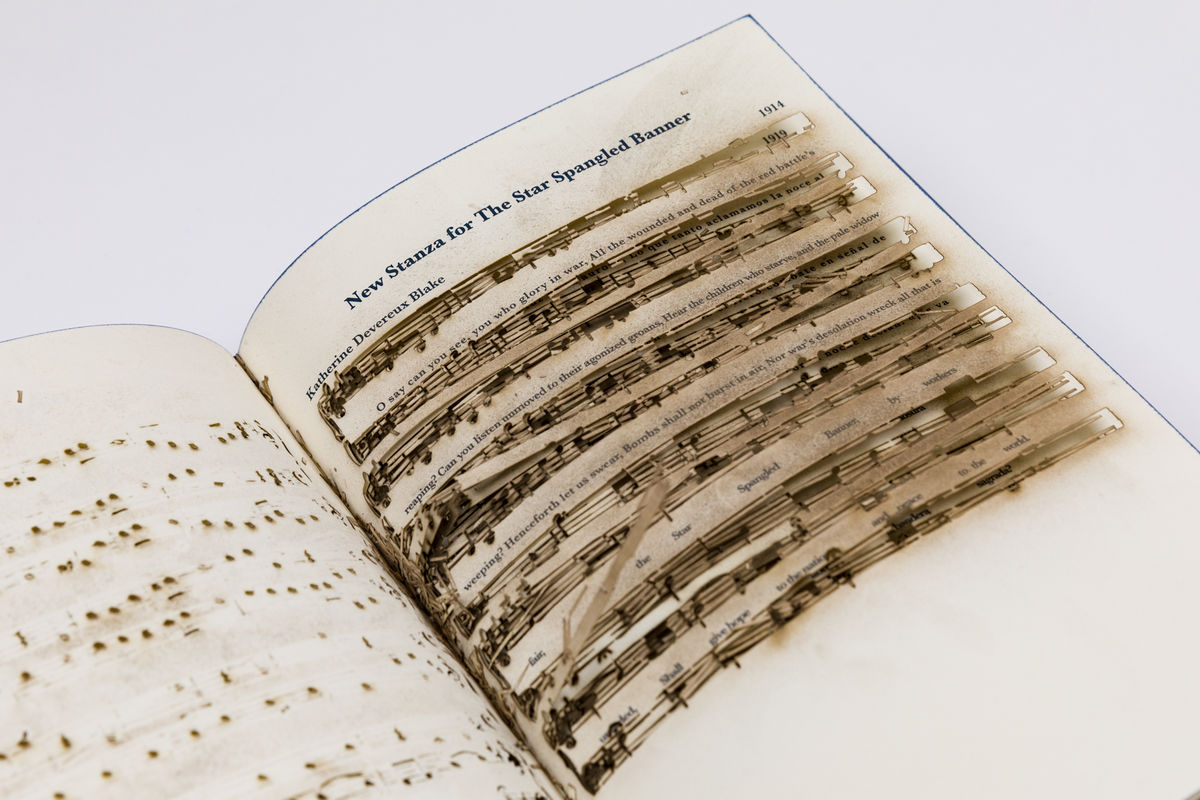

Collins’s The Star Spangled Banner: A Hymnal (2020) is comprised of 100 laser-cut leaves © Bethany Collins. Photo: Evan Jenkins

By deconstructing the anthem in myriad ways, Collins “challenges the notion of a cohesive American identity”. But her work also gestures towards a greater understanding of what it means to be patriotic, especially in light of the momentum of the Black Lives Matter movement and calls for the removal of Confederate and colonial monuments across the nation. “True patriotism includes casting a critical eye on our nation and its history, and making room for dissent with the status quo,” says Katie Delmez, a curator at the Frist Art Museum in Nashville where Collins’s The Star Spangled Banner series makes its debut this month as the centrepiece of her solo show Evensong.

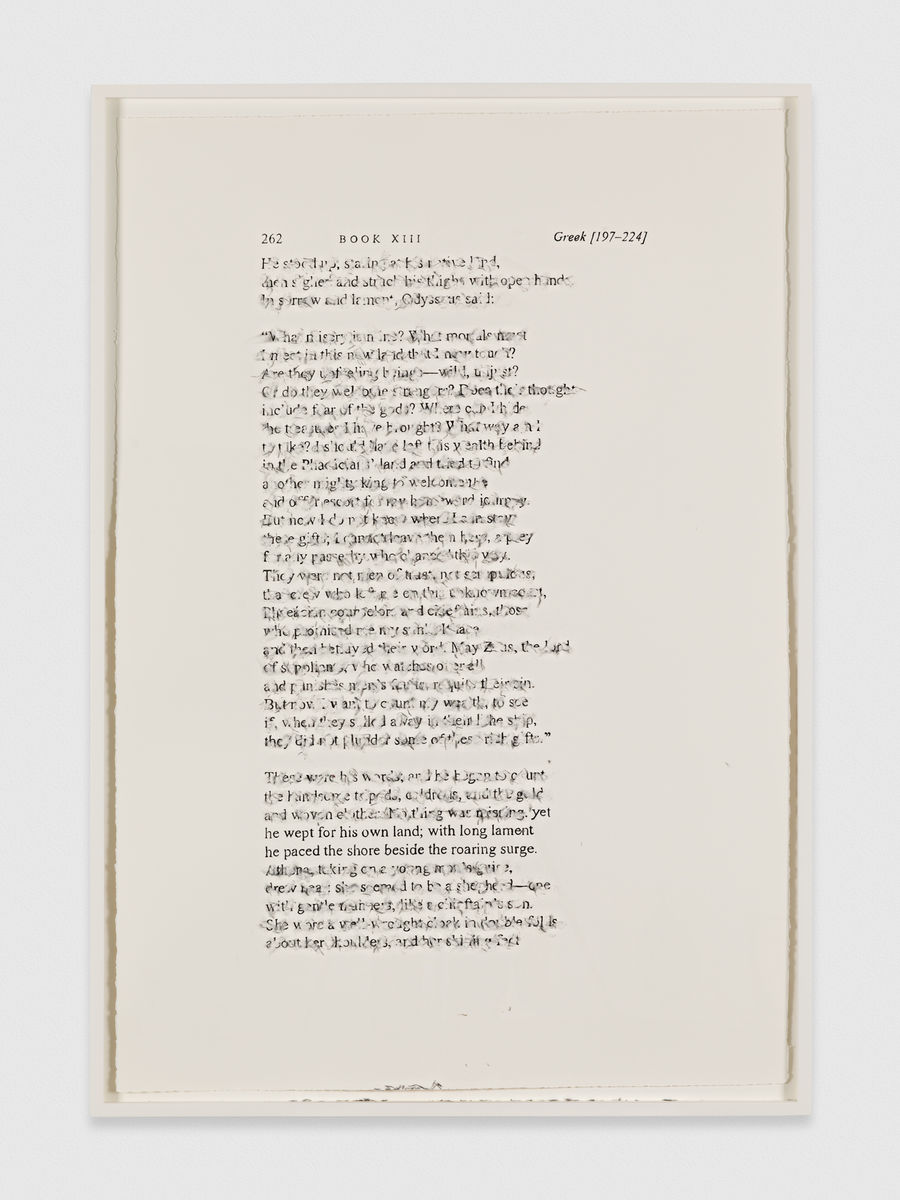

A detail of Bethany Collins’s The Odyssey: 1853 / 1932 / 1900 (2020) Courtesy of the artist and Patron Gallery; © Bethany Collins

The artist has always been drawn to interpretations of historical texts. Born in Montgomery, Alabama, Collins grew up in a Presbyterian church, where “we used to hold 72-hour Bible readings”, she says. “You would sign up for your hour—day or night—and you would come and read from the pulpit, hoping the next reader would show up to relieve you from your post.” Often, there was no one else at the church to hear the reading. The beauty of the ritual, says Collins, was that “a sacred text was still worthy of being read back into the world, even when no one was listening”.

It is this marathon reading style that will inform Collins’s live performance of The Star Spangled Banner hymn at the Frist in August. “Even after the fourth hour of hearing the same tune, even when no one is around to hear it, even when the singer is awfully off-key, I think democracy—with all its flaws—is still worthy of being sung back into the world.”