Artist to Watch: Anna Plesset

Mercer Contemporary / Oct 2, 2024 / by Editors / Go to Original

Portrait of Anna Plesset. Image courtesy of the artist.

NB: So what are some of your earliest memories of making art and how does it relate to your current show at Jack Barrett Gallery, American Paradise?

AP: I’ve been making art ever since I can remember. I grew up in a creative family: My grandfather was a painter and furniture designer and my grandmother was an interior designer, so their art and furniture always surrounded me. My grandfather had a particularly outsized influence on me and my work. When I was a teenager he started sending me his collection of art books little by little, and by the time I was in college I had amassed a sizable collection.

After grad school, during a residency in Giverny at the Terra Foundation, I started doing some research on the artist Lilla Cabot Perry whose studio I occupied during the program. She was a prominent member of theImpressionist community in Giverny in the late 1800’s and was a friend and neighbor of Monet. As I was looking through my books, I couldn’t find any mention of her outside of a photo credit in a book on Monet. That’s when I realized that my inherited collection was totally male-dominated and completely lacking the presence of women. I began thinking about how information is passed down and how history is authored and shared. These ideas have shaped my practice in a major way and directly relate to my current show American Paradise at Jack Barrett Gallery, which reframes the history of the Hudson River School to give visibility to the many 19th-century women landscapists who were affiliated with the movement, but who have been omitted from the canon.

Anna Plesset, Value Study 1: A View of the Catskill Mountain House / Copied from a picture by S. Cole copied from a picture by T. Cole / 1848, 2020. Oil and graphite on canvas. 15 3/8 x 23 7/16 inches.

NB: So how did you become familiar with the Hudson River School, and what was so enticing about it?

AP: I grew up in New York State and spent much of my childhood hiking in the Catskills, the Adirondacks, the White Mountains and beyond. So the geography that is depicted in the paintings of the Hudson River School is actually quite personal to me. The Hudson River School movement was always there in the background; I don’t remember when I specifically learned about it, but I knew the names Thomas Cole, Asher Durand, Albert Bierstadt and Frederic Church.

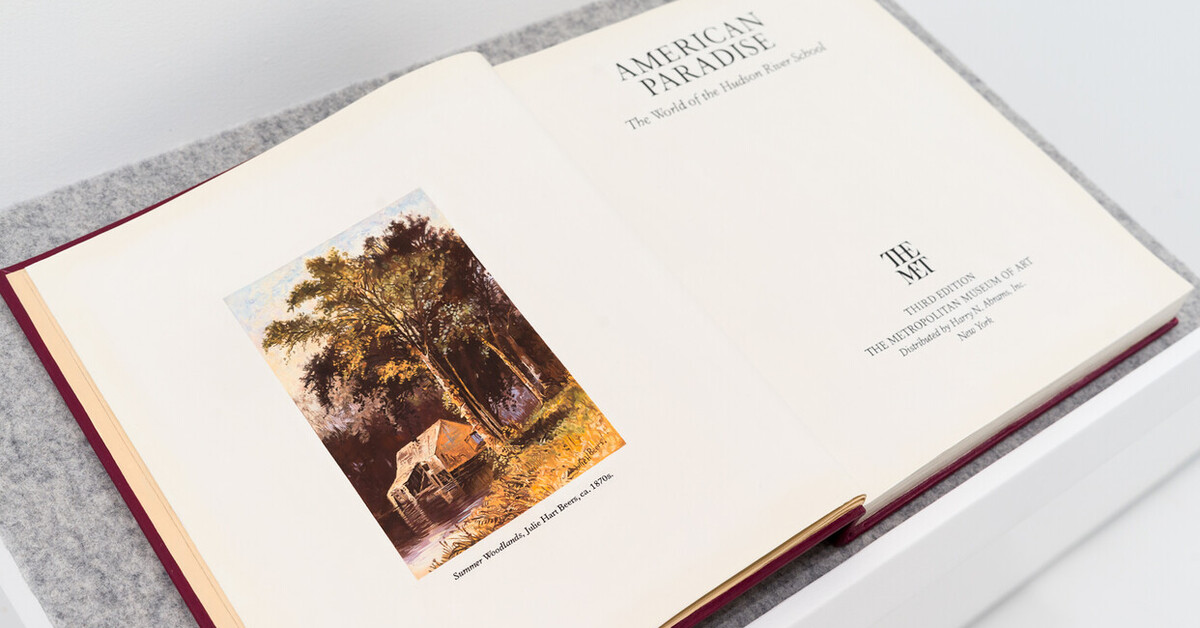

I was thinking about landscape and was doing some research on the White Mountains and the Catskills and I came across an exhibition at the Thomas Cole National Historic Site called Remember the Ladies that, at the time, was the only historical corrective I could find. I ordered the catalog immediately, and when it arrived I was surprised to see that it was this thin, 35-page booklet. I then started to look into major Hudson River School survey exhibitions, and was particularly interested in one at the Metropolitan Museum of Art that was put on in 1987 called American Paradise: the World of the Hudson River School. The exhibition, considered by many to be the definitive survey of this movement, and accompanying catalog featured 84 works by 25 male artists and not a single mention of a woman artist. We know that these women exhibited their work widely and they sold their work at prices on par with their male counterparts, but much of the work has been lost to time and they have been written out of the history books.

Making work about the Hudson River School was particularly enticing to me because it’s considered one of the most iconic American art movements, and the idea of it being founded by and comprised solely of men is a story that’s been perpetuated for nearly 200 years by books and institutions. It’s a period of art history—like most of art history—that was in dire need of correction. As an artist interested in reframing history and trying to make the invisible visible, this was really the perfect subject for me, and the Met’s exhibition title American Paradise was perfectly suited for critique.

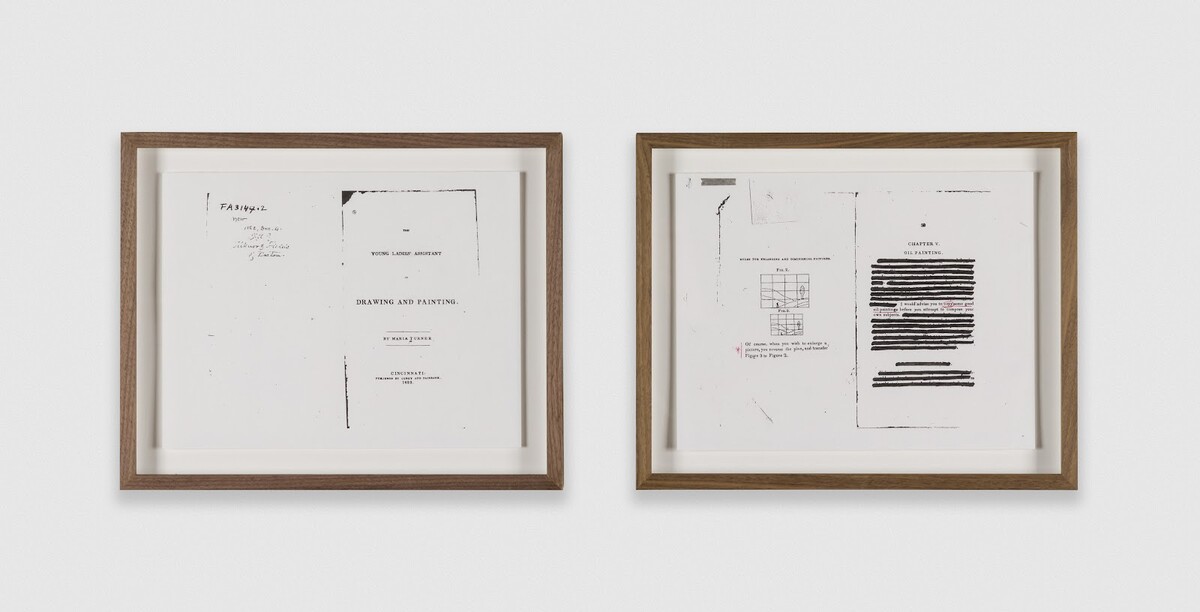

Anna Plesset, Copies from The Young Ladies’ Assistant in Painting and Drawing, 1833 (version 2), 2022. Carbon pencil on paper. Framed: 11 3/4 x 14 1/4 1 1/2 inches each.

NB: We found this quote in one of the works in American Paradise “I would advise you to copy some good oil paintings before you attempt to compose your own subjects.” Could you expand on this quote?

AP: This work speaks to the way that there are multiple versions of history and forms the conceptual basis for much of the work on view at American Paradise. Over the course of my research, I came across a book written by the artist and teacher Maria Turner in 1833 called The Young Ladies’ Assistant in Painting and Drawing, an art-making manual that was geared towards teaching young women various basic techniques.The work you’re referring to is a set of carbon pencil drawings that are meant to look like Xeroxes of 2 pages from the chapter on oil painting. In the first paragraph of that chapter, Turner suggests that women should copy some “good oil paintings”– which I infer means paintings by men–before they attempt to compose their own subjects. Historically, copying was very common not only as a learning tool, but also as a way to pay homage and confer status.

Around the same time that I found Turner’s manual I started learning about Sarah Cole, Thomas Cole’s sister. She was an artist who actively exhibited and sold her work in the mid 1800s, but only a handful of her work sexist today, maybe 5 or 6 paintings, the majority of which are copies of her brother’s paintings. This discovery of Sarah Cole’s work along with Turner’s suggestion to “copy some good oil paintings” inspired my Value Studies, a series of paintings in which I’m copying the works of several women associated with the Hudson River School, such as Cole, Louisa Davis Minot, Harriet Cany Peale, and Laura Woodward. The first Value Study painting I made references Sarah Cole’s A View of the Catskill Mountain House. This work, a copy of Thomas Cole’s Catskill Mountain House, is the same size as Thomas’ paintings and also on canvas. On the back of Sarah Cole’s painting, there’s an inscription that reads “A View of the Catskill Mountain House/ Copied from a picture by T. Cole / by S. Cole / 1848”. This inscription and the way it delivers so much information in an economical way informed the titles you see across my Value Studies series.

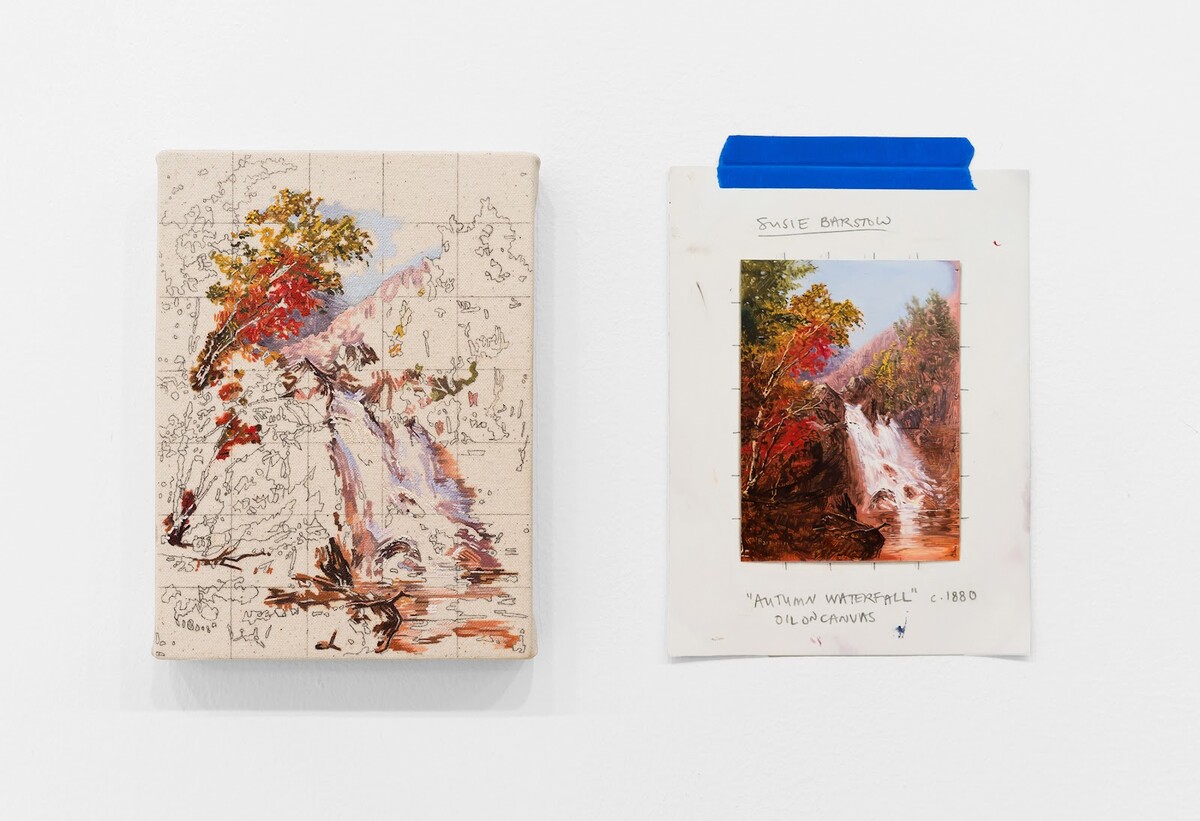

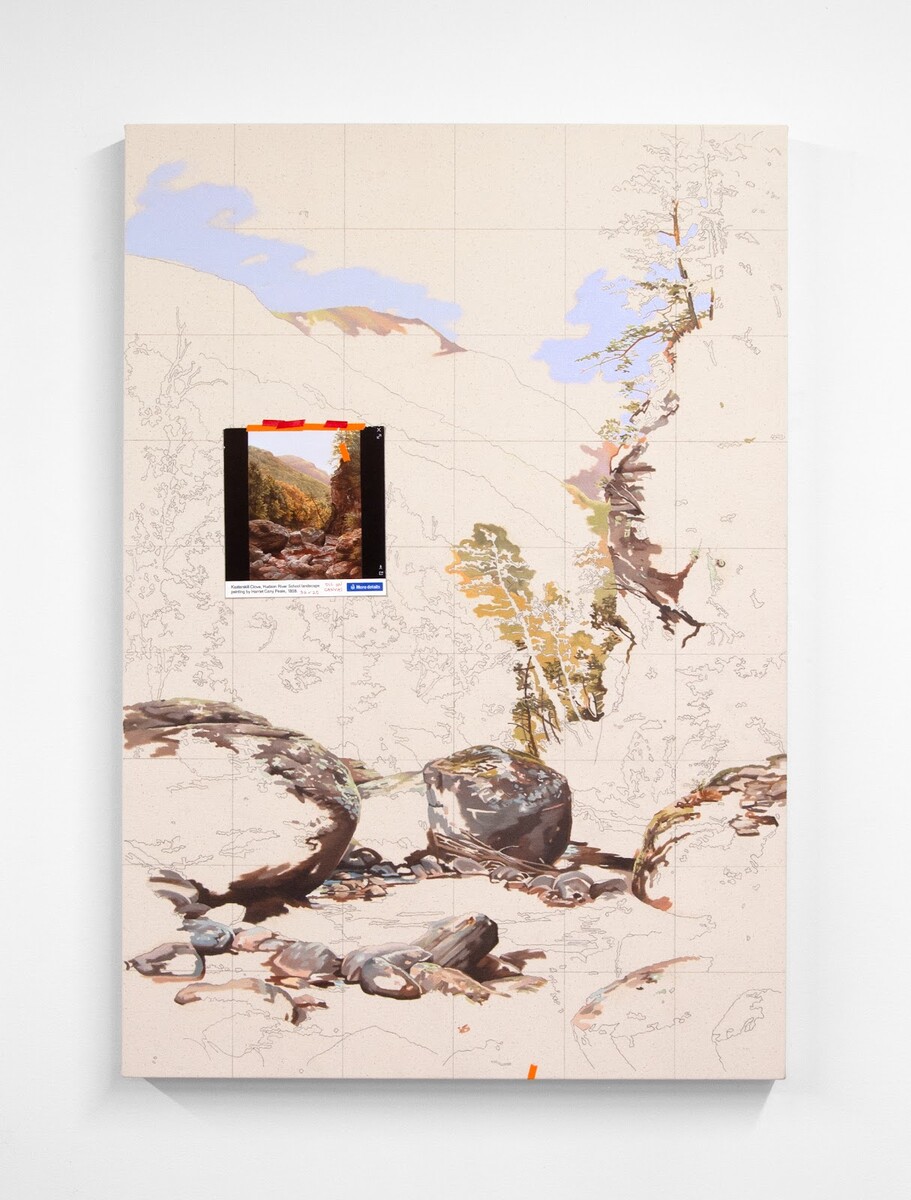

My Value Studies paintings are all the same size and facture as their originals, only in my versions the copies are in progress and are being painted from what look like printed screenshots of Google search results and other kinds of research material depicting the original artworks taped to the canvas or, as in Value Study 6, the wall. These references, all painted using trompe l’oeil, are like paintings within the larger paintings and are the actual true copies of the original works. In each Value Study painting, the unfinished part of the painting along with the trompe l’oeil portion make visible the act of historical recovery and acknowledge that work as always in progress.

Anna Plesset, Value Study 6: Autumn Waterfall / Copied from a picture by S. M. Barstow / c.1880, 2024. Oil on canvas and steel. 6 3/4 x 5 inches each.

NB: Your practice is very research based. Can you tell us how you find your references and the process of incorporating them into your work?

AP: My work requires a lot of research and because it’s largely about how history is authored and shared, the research often becomes part of the work itself. When I began working on this project in the summer of 2020 during the COVID lockdown, my only access to the paintings I was researching was through the internet. As a result, most of the references you see in the paintings are Google search results. I really wanted to incorporate those digital markers into the work because it’s an important element of this project in particular. Not only does it place it in time, the contemporary layered over the historical, but even if I did have access to museums and libraries it wouldn’t have helped since the vast majority of these paintings are not on view. The paintings by these women are rarely on display, many of them are in private collections, and there are very few catalogs featuring their work. So the fact that they’re not easily accessible is part of why we haven’t heard of these women, and situating them in the digital realm tells you a lot about where these paintings really live.

I mentioned earlier how I incorporate the reference materials into my work through trompe l’oeil, which is a centuries-old painting technique dating back to Greek and Roman times that literally means to fool the eye. I take a lot of cues from the 19th-century American trompe l’oeil painters, like painting 1:1 so that the viewer encounters the painted objects and ephemera the same way they might encounter them in their natural environments. This technique has become a really integral part of my practice because I feel that it enables me to challenge viewers’ perceptions, subvert their expectations, and help call into question what they see and therefore know.

Anna Plesset, Value Study 5: Kaaterskill Clove / Copied from a picture by Harriet C. Peale / 1858, 2024. Oil and graphite on canvas. 36 x 25 inches.

NB: Do you have any upcoming exhibitions or projects that you would like to share with us? And/or are there any other subjects or themes that you are currently researching?

AP: Well, I’m still working on the American Paradise project. I don’t feel like the number of works that are on view in the show right now can even do justice to the amount of correction that this history needs. So I’m actually still working on that project and later this month I’ll have a new Value Study painting on view in a group show at Perrotin in New York that opens October 29th.

Next month,, the Met is opening a major re-hanging of the American Wing in celebration of its 100th anniversary. They invited me to contribute to an audio project that brings contemporary voices into the collection and gallery spaces. In their Hudson River School galleries, you’ll be able to hear me talking about a Julie Hart Beers painting titled Ducks in the Woods, the second painting by a woman affiliated with the Hudson River School to enter the collection. The first painting, acquired in 2021, is a work also by Julie Hart Beers titled Summer Woodlands, which you might remember also appears in my show at Jack Barrett in a sculptural work called American Paradise (Third Edition).

Finally, in December, I’ll have some work on view at Art Basel in Miami with PATRON. It’s been a very productive year!