Meet artist Caroline Kent, whose bold mural is transforming Chicago’s Union Station

WBEZ / Feb 12, 2025 / by Elly Fishman / Go to Original

Caroline Kent stands in the center of her Humboldt Park home studio, surrounded by works in progress. Along one wall, four massive abstract paintings are partially complete, while smaller linen canvases sit scattered across her worktables. Nearby, adding to the vibrant energy of the space, is a collection of cut-paper shapes: experiments for a new project.

But at the moment, Kent, 49, isn’t discussing her to-do list. Instead, she trains her eye on her cat, precariously perched above the studio space atop a partition wall. “Daisy likes to keep eyes on me,” says Kent, nervously. She’s worried the calico will try to jump down. “You stay there,” she instructs the cat. “Just keep watch.”

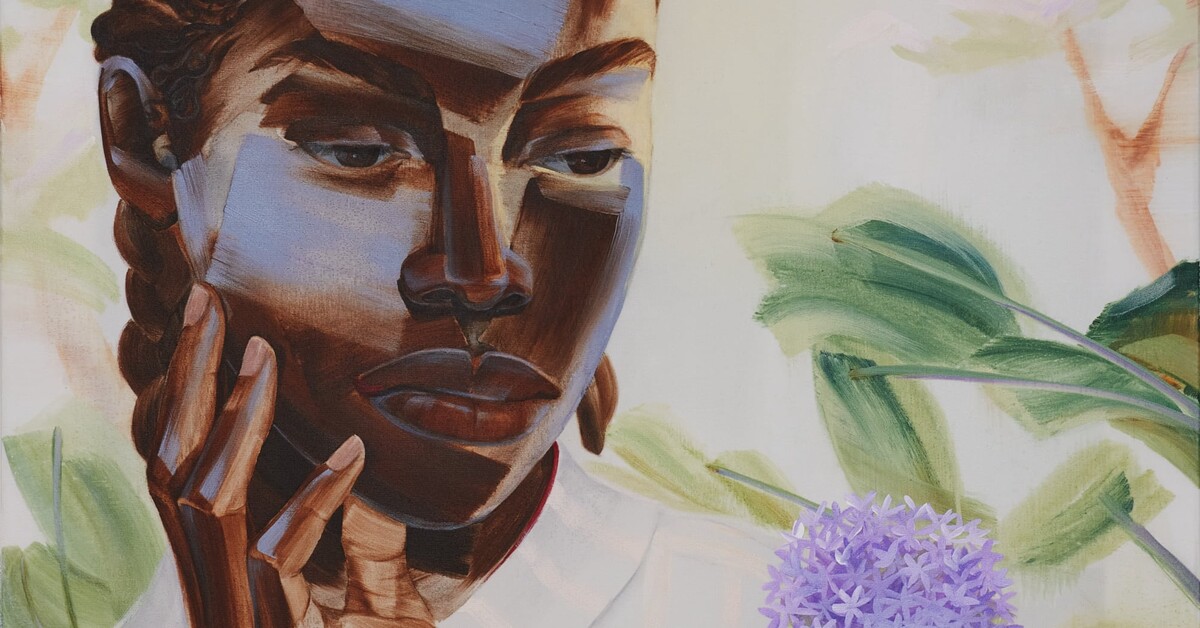

Daisy’s view is an enviable one. At a time when many contemporary artists are gravitating toward figurative painting, Kent remains committed to abstraction. The past three years have been the busiest of her career.

Since moving to Chicago in 2017 from Minnesota with her husband, artist Nate Young, Kent has staged 10 solo shows, notably a 2022 Chicago Works exhibit at the Museum of Contemporary Art; created installations in New York at the Museum of Modern Art in 2022 and another at the Queens Museum in 2023; and, most recently, delivered a site-specific mural in Chicago’s Union Station as part of the yearlong Art at Amtrak Public Art Program.

“Caroline’s work transcends all kinds of barriers,” says Debra Simon, the New York-based public curator of the Amtrak Art Project, who chose Kent for the public installation. “She’s a really versatile artist whose work is both beautiful and uplifting but also carries meaning behind it.”

Much of that meaning can be traced to her childhood in central Illinois. “The open sky, being able to look up and see stars and hear cicadas that loud,” reflects Kent, whose paintings evoke a similar sense of wonder. “The small kind of simple life, it gave me permission to daydream.”

As a kid, Kent did a lot of daydreaming with her identical twin sister. The two were constant companions. As girls, the sisters’ similarities — and differences — were a defining part of how they moved through the world. “As soon as you tell someone you’re an identical twin, people start to look for differences,” she says.

Kent shows no signs of slowing either. This spring, she will open her second solo exhibit at Patron Gallery in West Town and participate in another at the Smart Museum at the University of Chicago. In the summer, she’ll debut a new commission for the U.S. Embassy in Mexico City.

In many ways, Kent revisits those memories through her paintings, which explore and play with the concept of twinship. Created with meticulously layered textures and patterns — a zigzagging contour here, a whisper of flatness there — Kent’s work centers on her distinctive shapes. These forms invite multiple interpretations. Some resemble fragmented letters, while others evoke architectural ruins. Though similar, no two shapes are ever identical. “The shapes are never going to be repeated perfectly,” says Kent. “I like the idea that they come quite close, but they’re never identical.”

Nowhere is that interplay more alive than in Kent’s Daydreaming, her vibrant, 40-panel glass mural inside Union Station. The piece, which features a kaleidoscope of bold geometric shapes in luminous pinks, yellows, blues and greens, transforms the drab transit hub. It also offers a unique opportunity to take in Kent’s visual language in one place.

Seen together, says Jadine Collingwood, an associate curator at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Kent’s forms create an “abstract vocabulary of geometric shapes that can function like a language.”

Her gift is the ability to create a deliberately ambiguous language, one that resists a singular meaning. “I like the idea that the shapes can operate in a way where they are familiar but not entirely recognizable, allowing people to bring their own interpretations to them,” says Kent. “That kind of openness is important to me. It creates a dialogue between the work and the viewer.”

Back in Humboldt Park, Daisy has safely retreated from the ledge. Now Kent can calmly look over a series of new shapes that she’s been playing with for her show at the Smart Museum. She finds one of the forms, an irregular yellow silhouette that evokes a crown or castle wall, especially exciting. “I’ve never made one like this before,” she says. “I don’t know where it came from, and I just really love it.”

Kent’s delight is palpable; wonder, she says, is an emotion she tries to hold onto. One place she finds it is in her kids. All three — Kent and Young have two children together, and Young’s daughter lives with the couple part-time — regularly visit Kent in her studio. A heavy door separates her workroom from the living space, yet the sounds of Kent’s kids playing nearby and the buzz announcing finished laundry often drift into her studio. The artist calls the noise a welcome soundtrack. Recently, Kent and her 9-year-old have started painting together. “Her artwork is really interesting to me,” she says. “There’s something so innocent and precious and wonderful about it.”

Looking around the room, each piece feels like an extension of Kent’s life: a whimsical interplay of memory, family, and enduring curiosity. “It’s all integrated and blurred,” she says. “There’s always more to explore. That’s the joy — there’s no end.”