Claire Sherman: Petrichor

The Brooklyn Rail / Mar 18, 2025 / by Alex Grimley / Go to Original

In an 1878 interview, the American landscape painter George Inness made a strong distinction between “imitation,” his word for the precise verisimilitude of academic painting, and “unity.” What made a painting poetic and powerful, Inness explained, was the unity of formal means and representational ends, a holistic approach in which (I’m paraphrasing) every detail of the picture is subordinated to expressing the vision of nature that impressed the artist. Inness was focused on communicating the somatic, sensory qualities of landscape—how it feels rather than how it looks. This approach to landscape painting gradually became the dominant one, and today landscape is the medium through which some of the most original and exceptional recent painting has emerged, as in the work of artists Eric Aho, Lucas Arruda, Hayley Barker, and Claire Sherman.

Petrichor (described in the exhibition catalogue by the conservationist Terry Tempest Williams as “the unmistakable scent of rain before it falls”) is Sherman’s fifth show at DC Moore in just over a decade and the first in several years to feature paintings of cliffs, crevices, and caves. The show is more or less evenly divided between these works, most of which stand between seven and eight feet tall, and smaller grass and wildflower pictures like those featured in Sherman’s previous show. In addition to size and subject, these two bodies of work diverge in their palette and paint handling.

The grass paintings, with their shallow, frontal, sometimes impenetrable space and rich shadows, are more familiar. The largest among these works, Grass (2024), which in my view is the strongest, captures a moment near dusk, when colors close at hand begin to dissolve and retreat into darkness. A rock in the bottom left corner alone orients the viewer to the picture’s space, and patches of grass on the opposite corner and on the left edge remain just barely illuminated, leading the eye into the farthest recesses of the scene where the grass is lit with a bluish glow. Sherman renders these planes of space and areas of fading light with remarkable subtlety. Enshadowed stalks and leaves are nestled throughout in shades of dark green, umber, and maroon, underscoring the virtually inexhaustible detail in this painting.

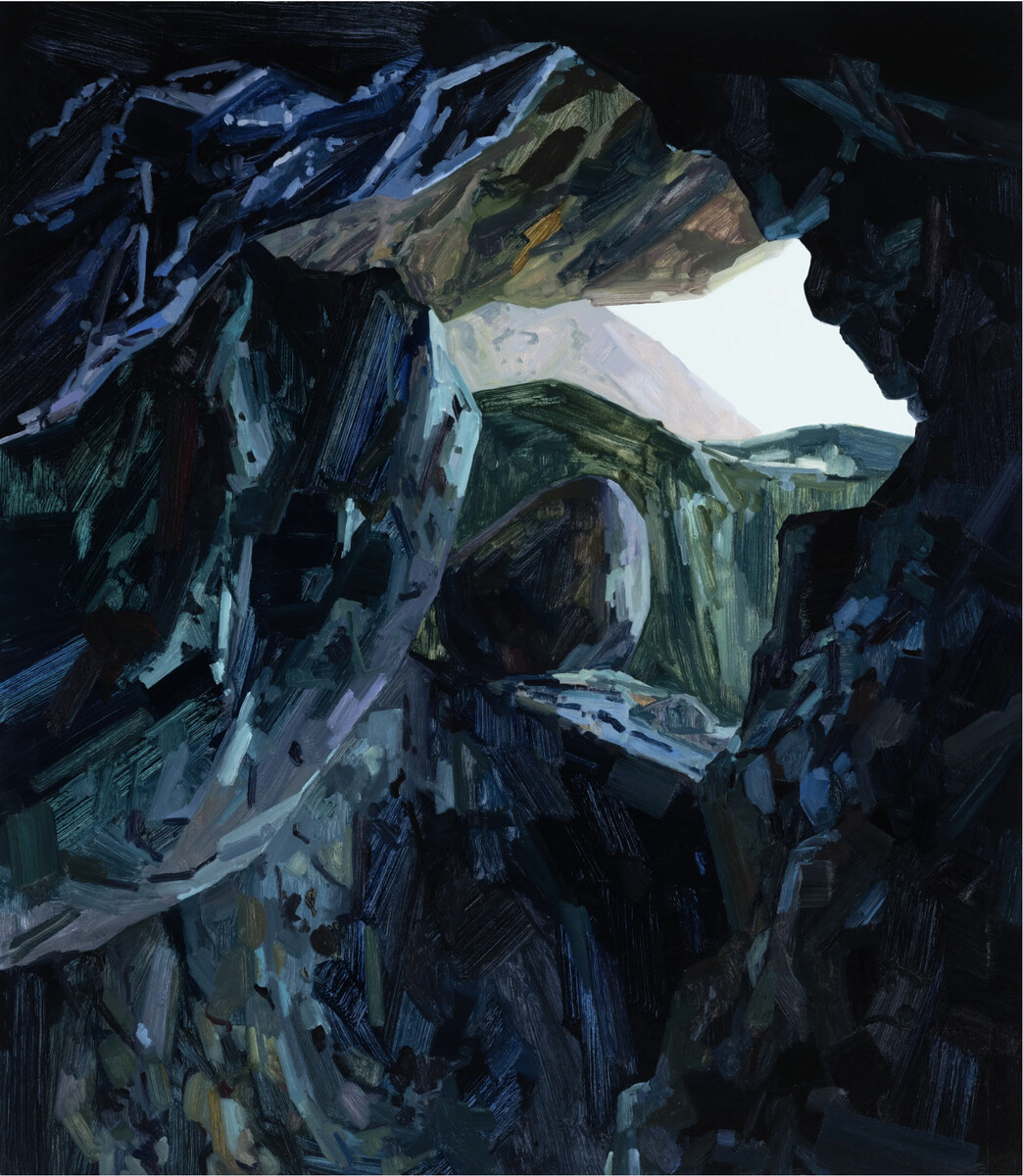

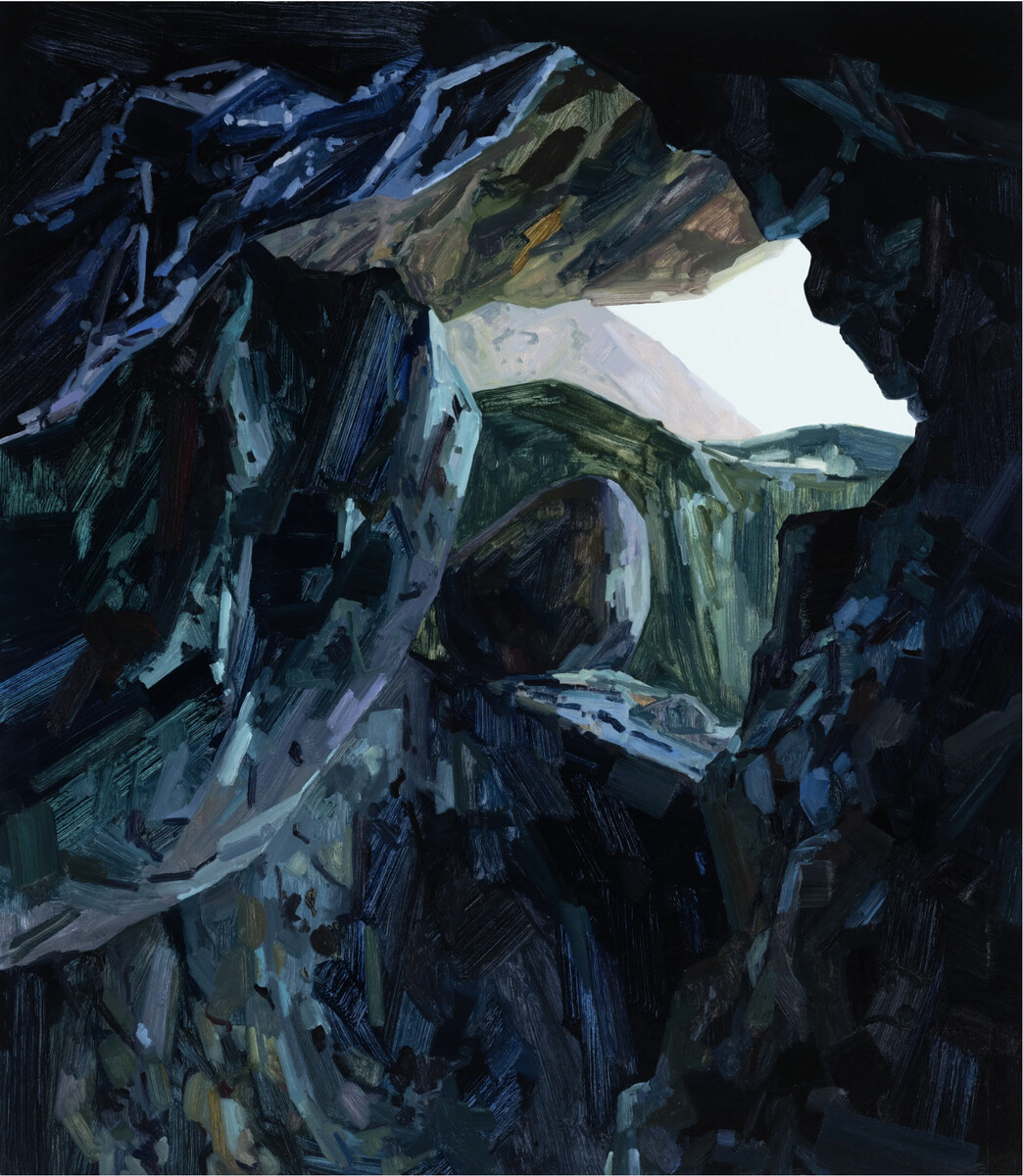

Sherman’s approach to representing the two different types of scenery offers a distinction that I haven’t seen presented so starkly before—that between drawing and mark making. In the wildflower works, angular and arcing lines fly like sparks across the surface, sprouting up and shooting out from the edges of the painting into a tangle of layers, of light and shadow. The two darkly colored Canyon paintings (2023 and 2024) are built from broad brushstrokes. Sherman utilizes the emphatic materiality of these marks to descriptive ends; their direction helps describe the jagged rock surfaces and their glossy sheen, contrasted with the matte light blue sky, subtly amplifies the canyon’s interior highlights. This approach is also evident in the smallest of the paintings titled Cave (2023), one of the show’s standouts, which, with its construction of light and form from small, discrete brushstrokes evokes the very late landscapes of Cézanne.

An onrush of marks in the angular and lightly toned Canyon (2024) body forth toward the viewer in a descent that calls to mind the vertical spatial organization common to Chinese landscape painting. This painting, however, verges on abstraction in that its constituent parts are unified so as to make a holistic sensory appeal of massiveness, density, and gravity. A similarly intense pressure can be found in the unrelenting Rock Wall (2024), which, but for the solid ground at the bottom, might read as a gust of wind, a tornado, or something otherwise immaterial. In this painting, precise description is kept to a minimum, and the overall sensation is one of sheer force. In Cave (2023), this interplay between the obdurate and the immaterial also plays out, though less successfully, as the two qualities work at cross purposes, with the striated layers of rock appearing draped like a fabric over the faraway cave passage.

I found Petrichor to be an ambitious show. The best works included in this exhibition both push against and expand upon the conventions of landscape painting, offering a visual experience that is simultaneously emphatically tactile and somatic. Claire Sherman is a resourceful and inventive painter, who like the artists I mentioned at the outset, continues to present unfamiliar perspectives on the familiar natural world.

Petrichor (described in the exhibition catalogue by the conservationist Terry Tempest Williams as “the unmistakable scent of rain before it falls”) is Sherman’s fifth show at DC Moore in just over a decade and the first in several years to feature paintings of cliffs, crevices, and caves. The show is more or less evenly divided between these works, most of which stand between seven and eight feet tall, and smaller grass and wildflower pictures like those featured in Sherman’s previous show. In addition to size and subject, these two bodies of work diverge in their palette and paint handling.

Claire Sherman, Canyon, 2023. Oil on canvas, 96 x 78 inches Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York.

The grass paintings, with their shallow, frontal, sometimes impenetrable space and rich shadows, are more familiar. The largest among these works, Grass (2024), which in my view is the strongest, captures a moment near dusk, when colors close at hand begin to dissolve and retreat into darkness. A rock in the bottom left corner alone orients the viewer to the picture’s space, and patches of grass on the opposite corner and on the left edge remain just barely illuminated, leading the eye into the farthest recesses of the scene where the grass is lit with a bluish glow. Sherman renders these planes of space and areas of fading light with remarkable subtlety. Enshadowed stalks and leaves are nestled throughout in shades of dark green, umber, and maroon, underscoring the virtually inexhaustible detail in this painting.

Sherman’s approach to representing the two different types of scenery offers a distinction that I haven’t seen presented so starkly before—that between drawing and mark making. In the wildflower works, angular and arcing lines fly like sparks across the surface, sprouting up and shooting out from the edges of the painting into a tangle of layers, of light and shadow. The two darkly colored Canyon paintings (2023 and 2024) are built from broad brushstrokes. Sherman utilizes the emphatic materiality of these marks to descriptive ends; their direction helps describe the jagged rock surfaces and their glossy sheen, contrasted with the matte light blue sky, subtly amplifies the canyon’s interior highlights. This approach is also evident in the smallest of the paintings titled Cave (2023), one of the show’s standouts, which, with its construction of light and form from small, discrete brushstrokes evokes the very late landscapes of Cézanne.

Claire Sherman, Cave, 2023. Oil on canvas, 48 x 42 inches. Courtesy the artist and DC Moore Gallery, New York.

An onrush of marks in the angular and lightly toned Canyon (2024) body forth toward the viewer in a descent that calls to mind the vertical spatial organization common to Chinese landscape painting. This painting, however, verges on abstraction in that its constituent parts are unified so as to make a holistic sensory appeal of massiveness, density, and gravity. A similarly intense pressure can be found in the unrelenting Rock Wall (2024), which, but for the solid ground at the bottom, might read as a gust of wind, a tornado, or something otherwise immaterial. In this painting, precise description is kept to a minimum, and the overall sensation is one of sheer force. In Cave (2023), this interplay between the obdurate and the immaterial also plays out, though less successfully, as the two qualities work at cross purposes, with the striated layers of rock appearing draped like a fabric over the faraway cave passage.

I found Petrichor to be an ambitious show. The best works included in this exhibition both push against and expand upon the conventions of landscape painting, offering a visual experience that is simultaneously emphatically tactile and somatic. Claire Sherman is a resourceful and inventive painter, who like the artists I mentioned at the outset, continues to present unfamiliar perspectives on the familiar natural world.