Review | Bethany Collins : Dusk

The Curatorial Blonde / Oct 11, 2025 / by Caira Moreira / Go to Original

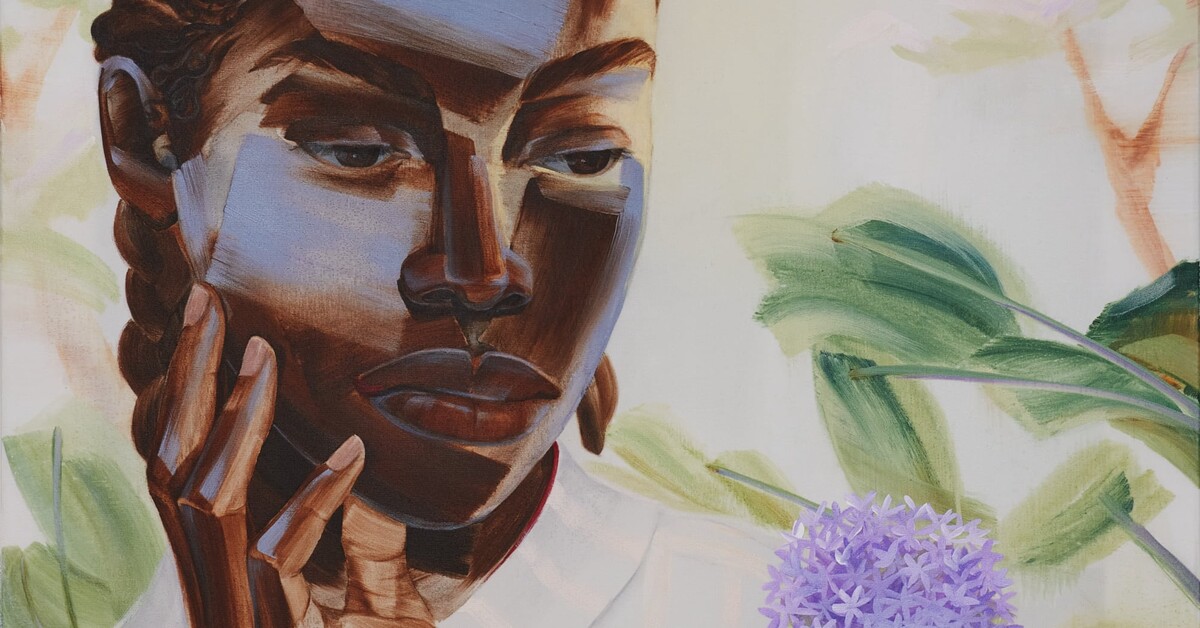

Bethany Collins’s Dusk, her fourth solo exhibition at PATRON, unfolds as an extended meditation on the instability of language and the fragility of cultural memory. Positioned in the liminal moment between light and darkness, the exhibition stages the dissolution of certainty, examining how national symbols, literary canons, and collective songs function as both repositories of meaning and instruments of erasure. Collins continues to interrogate the materiality of language—not as a fixed vessel of truth but as a contested terrain where ideologies are inscribed, reworked, and ultimately undone.

Central to the exhibition are three new works from The Battle Hymn of the Republic series. By engaging one of the most familiar contrafacta in the American songbook, Collins foregrounds the mutability of national narratives. The song, historically rewritten to serve abolitionist, suffragist, labor, and even secessionist agendas, embodies the contradictions of American identity formation. Collins destabilizes its presumed unity by fragmenting its floral metaphors—symbols of grief and renewal—into gestural marks that hover at the edge of legibility. What emerges is not a clear articulation of voice but rather a dissolution into noise, exposing the instability of a collective anthem once thought to unify.

This interrogation of symbolism extends to Collins’s graphite drawings after 19th-century floral lithographs from the Library of Congress. These commercially reproduced images of roses—domestic icons that later became candidates for the national flower—are here rendered unstable, their surfaces shrouded in charcoal dust. Collins’s intervention destabilizes the rose’s position as a symbol of beauty, patriotism, and permanence, re-situating it within a more fraught, contested visual lexicon.

The most ambitious works in the exhibition are Collins’s engagements with Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick, long read as an allegorical “American Bible.” In Or, The Whale. Vol. 1 (2024–25), Collins transcribes the entirety of Melville’s text in iron gall ink on onion skin paper, enacting both devotion and futility. The ink—historically prized for its permanence but chemically predisposed to self-destruction—renders the act of preservation paradoxical. The transcription becomes an embodied performance of care and loss, inscribing the inevitability of decay into the archive itself.

The Loss drawings and related sculptures extend this logic through erasure. Collins selectively effaces passages from Moby-Dick, isolating only descriptions of the sea in its most violent, apocalyptic register. The resulting fragments foreground the ocean not as a backdrop but as a destabilizing, relentless force—language pared down to elemental residue. Nearby eraser-dust sculptures, the physical remnants of this process, function as memorials to absence: linguistic monuments to what has been rubbed away.

Taken together, the works in Dusk position language as both a structuring device and a site of collapse. Collins resists the temptation to stabilize meaning; instead, she underscores the precarity of narratives once thought immutable. The exhibition’s title is apt: dusk is neither day nor night but a threshold condition, a collective entry into ambiguity. In Collins’s hands, language is not a guarantor of permanence but a fragile, unstable medium whose endurance is always provisional.

By staging this instability, Dusk offers a critical reflection on the cultural and political work of language in America. In Collins’s practice, texts and symbols are not neutral but deeply implicated in histories of power, erasure, and reinvention. What persists, the exhibition suggests, is not clarity but the shared act of entering darkness together—an insistence on the necessity of dwelling in uncertainty.