Eight Questions for Bethany Collins

Art Papers / May 7, 2016 / by Buzz Spector / Go to Original

Below, critical writer, educator, and multidisciplinary artist Buzz Spector poses eight questions to Bethany Collins, the 2015 recipient of Georgia’s Hudgens Prize—for which Spector was a Juror—and a contributor to ART PAPERS’ magazine and live lecture series. Collins’ multidisciplinary work takes place at an intersection of race and language—a point she explores in text and image variously through erasure, texture, doubling, or a visible dialogue between simple black and white hues. (Holland Cotter, writing in The New York Times, has suggested, Collins’ primary medium is “language itself … intrinsically racialized.”) Collins’ works have been exhibited in solo and group exhibitions nationwide, including the High Museum of Art, the Museum of Contemporary Art of Georgia, and the Studio Museum in Harlem, where she was an Artist-in-Residence. She is also a finalist for the Prix Canson, which recognizes an artist who has contributed to the field of works on paper. The Prix Canson finalists’ exhibition will be on view at the Drawing Center from June 22—July 1, 2016.

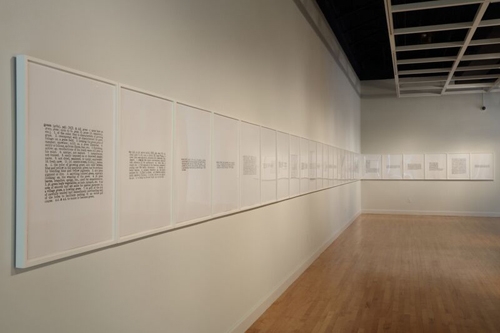

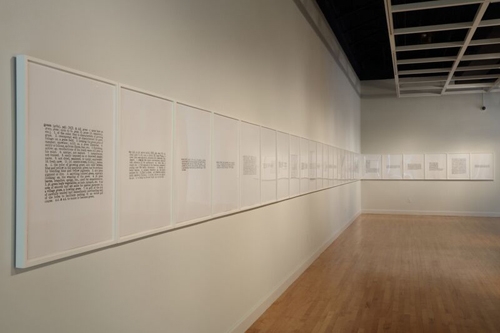

Bethany Collins, Between Green & Violet, 2014-15, toner and graphite on American Masters paper

[photo: Mike Jensen, courtesy of the Hudgens Center for the Arts]

1. In interviews and previous public statements you’ve talked about the problematic binaries attached to racial identity. Since your art is often executed in a palette of black and/or white, what other aspects of the work destabilize this overt chromatic opposition?

The visible presence of the binary exists in almost every series I’m working on, from the White Noise chalk on chalkboard works to the erased definitions on American Masters bright white paper in the Contronym series. What consistently complicates and refutes that binary is the residue—the residue of language altered, blurred or partially erased presents a more complicated “third way”. Not to mention, the Contronym series itself destabilizes that either/or proposition. Contronyms are words which contain their own opposite definitions. Quiddity, for example, is the very essence of a thing and a trifling nothing. Highlighting those contradictions through erasure tackles the absurdity of our expectations of a kind of singular clarity.

2. I came away from the Hudgens Prize juror visit to your studio with a vivid memory of the detritus left behind as you made your work, in particular the eraser shavings on the floor or, in one case, neatly piled on a table. Tell me about how these piles relate to your investigations of language? Of landscape?

I remember how quickly you saw the work and underneath it. The traces of language, as subject and process, are evident in the flecks of paper and Pink Pearl eraser clinging to the surface or falling to the floor below. From the charcoal fingerprints in the The Southern Review, which show the history of my touch and my reading, to chalk dust trapped in felt erasers. In all these ways, I’m interested in the ability of the residue to retain the text’s essence in changed form. To be the same yet wholly different.

3. The large blackboard works you included in your Hudgens Art Center show last year included two orders of lettering: handwritten sentences that were smeared to become partially illegible, and clusters of smaller individual letterforms, easily recognized but impossible to read. Are you making a distinction between the illegible and the unreadable?

In those White Noise chalk on chalkboard works, I think of that ordering of language as my give-and-take with the viewer. The partially illegible, erased text is the same language as the impossible to read clusters of tiny letters. The first is difficult but possible to read. The second necessitates that you trust what I’ve told you that I’ve written. Both are ways for me to control not only the problematic language that necessitated the chalkboard piece, but also the viewer’s new relationship to it.

4. Your work has a special quality of found language subjected to acts of erasure that never really obscure our sense of where these texts were taken from. This kind of “failed” erasure is reminiscent of the device in philosophy called sous rature, where contradictions in a text are preserved in print but struck through by a line that still allows them to be read. Do you mean for these erasures to expose contradictions?

Yes. Absolutely. The paradoxical choice to erase, but to leave standing, to expose the contradiction, to frustrate the viewer’s gaze and to control a new reading of the text…all of these outcomes feel like an exertion of mastery over this language that initially feels so unwieldy to me.

5. I keep bringing up forms of erasure in asking about your methods, but there’s another aspect to the gesture of erasure: that of its similarity to a caress. Perhaps there’s a love of the texts you select, for which their unmaking by eraser is also a kind of undressing.

I cannot help but see my obsession with language through the lens of my body. I’ve written a thousand tiny illegible letters, but only until my hand hurts. In the first The Southern Review, I initially threw away those imperfect, messy, and ripped pages until realizing that my sooty fingerprints all over the surface was the work. And not water, but my spit makes the Contronym erasure works possible, eating into the surface of the paper. So, there is pain and desire intertwined, I think, in every one of those actions. And caress is inseparable, or maybe indistinguishable here, from destruction.

6. Your current blind embossing works ask us to see the whiteness—or blackness—of the paper on which their words are stamped as a kind of camouflage. Can you speak to the critical context of this disguise?

The first work I embossed was the [Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department] of 2015, which was also the first text I’ve used without any historical distance. It’s a current document of all the reasons leading up to Ferguson, Missouri, as most of us know it. When the report was published, I remember one response: that reading the report was like “being told that water is wet.” From a distance, the work appears simply as a wall of white. Up close, though, the braille-like text protruding from the surface is legible, but difficult to read. So even that which has been made clear, that which is impossible to deny, can still be hard to see…which is both the mechanics and the context for the work.

7. When did you first want to be an artist? How has your upbringing in the South informed the direction of your art?

At the University of Alabama, I majored in photojournalism as a creative profession that might also offer financial stability. What I enjoyed about that work was the immediacy of the questions asked and answered in real time, daily. What I lacked—and I realized this after the last assignment I covered, involving multiple fatalities—was the desire to assert/insert myself into the story. I find in my studio practice then the same love of well-crafted questions, and even just the potential of answers. In every work, I’m longing for that resolution.

8. The Hudgens Prize is intended to be a “transformational opportunity” for a Georgia artist. The substantial cash award can obviously change one’s personal circumstances, but there are other aspects of the competition and jurying that must also matter. Can you share your own experience of the process?

The inseparable impact and value of the Hudgens Prize is in the cash award being paired with a lengthy conversation between finalists and jurors. Together, those two charge us with the work to come. Last year, I had a visit with you, Shannon Fitzgerald, and Hamza Walker, who all came to my studio so prepared and familiar with my work, yet so open. And a year after our studio visit, Buzz, I’m still mulling over these ideas of erasure as failed act, of erasure as amorous act, of the act of erasure as putting one’s body in the crosshairs… It’s our conversation unfurling over the long-haul that I hold as so particularly valuable.

Bethany Collins, Untitled (Technological Guilt), 2016, charcoal on found paper [photo: Mike Jensen, courtesy of the Hudgens Center for the Arts]

Bethany Collins, Between Green & Violet, 2014-15, toner and graphite on American Masters paper

[photo: Mike Jensen, courtesy of the Hudgens Center for the Arts]

1. In interviews and previous public statements you’ve talked about the problematic binaries attached to racial identity. Since your art is often executed in a palette of black and/or white, what other aspects of the work destabilize this overt chromatic opposition?

The visible presence of the binary exists in almost every series I’m working on, from the White Noise chalk on chalkboard works to the erased definitions on American Masters bright white paper in the Contronym series. What consistently complicates and refutes that binary is the residue—the residue of language altered, blurred or partially erased presents a more complicated “third way”. Not to mention, the Contronym series itself destabilizes that either/or proposition. Contronyms are words which contain their own opposite definitions. Quiddity, for example, is the very essence of a thing and a trifling nothing. Highlighting those contradictions through erasure tackles the absurdity of our expectations of a kind of singular clarity.

2. I came away from the Hudgens Prize juror visit to your studio with a vivid memory of the detritus left behind as you made your work, in particular the eraser shavings on the floor or, in one case, neatly piled on a table. Tell me about how these piles relate to your investigations of language? Of landscape?

I remember how quickly you saw the work and underneath it. The traces of language, as subject and process, are evident in the flecks of paper and Pink Pearl eraser clinging to the surface or falling to the floor below. From the charcoal fingerprints in the The Southern Review, which show the history of my touch and my reading, to chalk dust trapped in felt erasers. In all these ways, I’m interested in the ability of the residue to retain the text’s essence in changed form. To be the same yet wholly different.

3. The large blackboard works you included in your Hudgens Art Center show last year included two orders of lettering: handwritten sentences that were smeared to become partially illegible, and clusters of smaller individual letterforms, easily recognized but impossible to read. Are you making a distinction between the illegible and the unreadable?

In those White Noise chalk on chalkboard works, I think of that ordering of language as my give-and-take with the viewer. The partially illegible, erased text is the same language as the impossible to read clusters of tiny letters. The first is difficult but possible to read. The second necessitates that you trust what I’ve told you that I’ve written. Both are ways for me to control not only the problematic language that necessitated the chalkboard piece, but also the viewer’s new relationship to it.

4. Your work has a special quality of found language subjected to acts of erasure that never really obscure our sense of where these texts were taken from. This kind of “failed” erasure is reminiscent of the device in philosophy called sous rature, where contradictions in a text are preserved in print but struck through by a line that still allows them to be read. Do you mean for these erasures to expose contradictions?

Yes. Absolutely. The paradoxical choice to erase, but to leave standing, to expose the contradiction, to frustrate the viewer’s gaze and to control a new reading of the text…all of these outcomes feel like an exertion of mastery over this language that initially feels so unwieldy to me.

5. I keep bringing up forms of erasure in asking about your methods, but there’s another aspect to the gesture of erasure: that of its similarity to a caress. Perhaps there’s a love of the texts you select, for which their unmaking by eraser is also a kind of undressing.

I cannot help but see my obsession with language through the lens of my body. I’ve written a thousand tiny illegible letters, but only until my hand hurts. In the first The Southern Review, I initially threw away those imperfect, messy, and ripped pages until realizing that my sooty fingerprints all over the surface was the work. And not water, but my spit makes the Contronym erasure works possible, eating into the surface of the paper. So, there is pain and desire intertwined, I think, in every one of those actions. And caress is inseparable, or maybe indistinguishable here, from destruction.

6. Your current blind embossing works ask us to see the whiteness—or blackness—of the paper on which their words are stamped as a kind of camouflage. Can you speak to the critical context of this disguise?

The first work I embossed was the [Department of Justice report on the Ferguson Police Department] of 2015, which was also the first text I’ve used without any historical distance. It’s a current document of all the reasons leading up to Ferguson, Missouri, as most of us know it. When the report was published, I remember one response: that reading the report was like “being told that water is wet.” From a distance, the work appears simply as a wall of white. Up close, though, the braille-like text protruding from the surface is legible, but difficult to read. So even that which has been made clear, that which is impossible to deny, can still be hard to see…which is both the mechanics and the context for the work.

7. When did you first want to be an artist? How has your upbringing in the South informed the direction of your art?

At the University of Alabama, I majored in photojournalism as a creative profession that might also offer financial stability. What I enjoyed about that work was the immediacy of the questions asked and answered in real time, daily. What I lacked—and I realized this after the last assignment I covered, involving multiple fatalities—was the desire to assert/insert myself into the story. I find in my studio practice then the same love of well-crafted questions, and even just the potential of answers. In every work, I’m longing for that resolution.

8. The Hudgens Prize is intended to be a “transformational opportunity” for a Georgia artist. The substantial cash award can obviously change one’s personal circumstances, but there are other aspects of the competition and jurying that must also matter. Can you share your own experience of the process?

The inseparable impact and value of the Hudgens Prize is in the cash award being paired with a lengthy conversation between finalists and jurors. Together, those two charge us with the work to come. Last year, I had a visit with you, Shannon Fitzgerald, and Hamza Walker, who all came to my studio so prepared and familiar with my work, yet so open. And a year after our studio visit, Buzz, I’m still mulling over these ideas of erasure as failed act, of erasure as amorous act, of the act of erasure as putting one’s body in the crosshairs… It’s our conversation unfurling over the long-haul that I hold as so particularly valuable.

Bethany Collins, Untitled (Technological Guilt), 2016, charcoal on found paper [photo: Mike Jensen, courtesy of the Hudgens Center for the Arts]