Contemplating Disembodiment in the Work of Liat Yossifor

Dopplehouse Press / May 18, 2020 / by Susan Power / Go to Original

Our experience of time and space has been radically disrupted by the threat of the pandemic; its scope and sobering impact both intimate and distant. Yet this existential crisis can promote a new way of being in the world. With so many aspects of our lives on hold, the current moment offers a rare opportunity to reflect upon the “state of things.”

Like the eponymous1982 filmby Wim Wenders, which revolves around a science fiction film cast and crew stranded together on location when the production is stalled due to sudden lack of funds, Liat Yossifor’s latest body of work was on its way to Sydney, Australia for a solo show at Fox Jensen Gallery scheduled to open on March 28 when it became stranded in shipping crates, postponed in the voyage to its destination, and ultimately consigned to a screen, thus suffering a fate similar to that of nearly all exhibitions slated for this Spring at galleries and museums around the globe.

While greatly diminishing the work’s impact, paradoxically, the online viewing room of Fox Jensen offers potentially greater visibility for the work. Does it do so at the expense of its living vitality and vibrant energy?

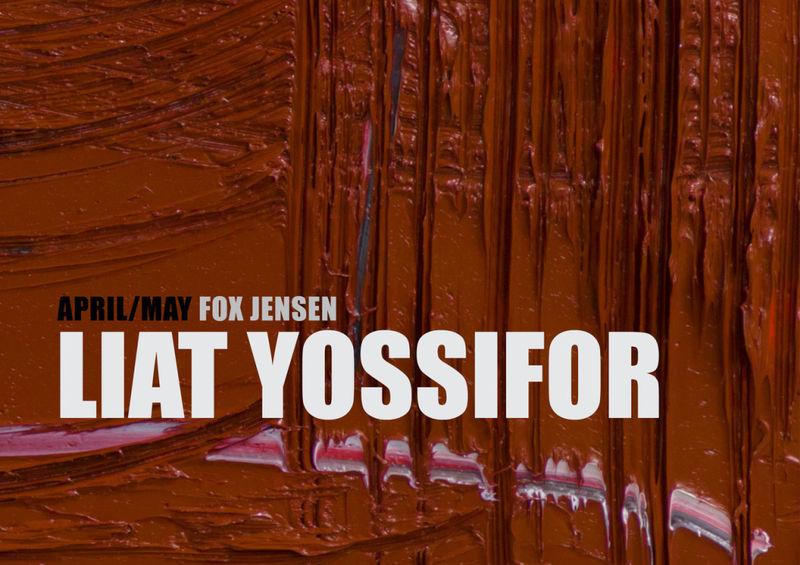

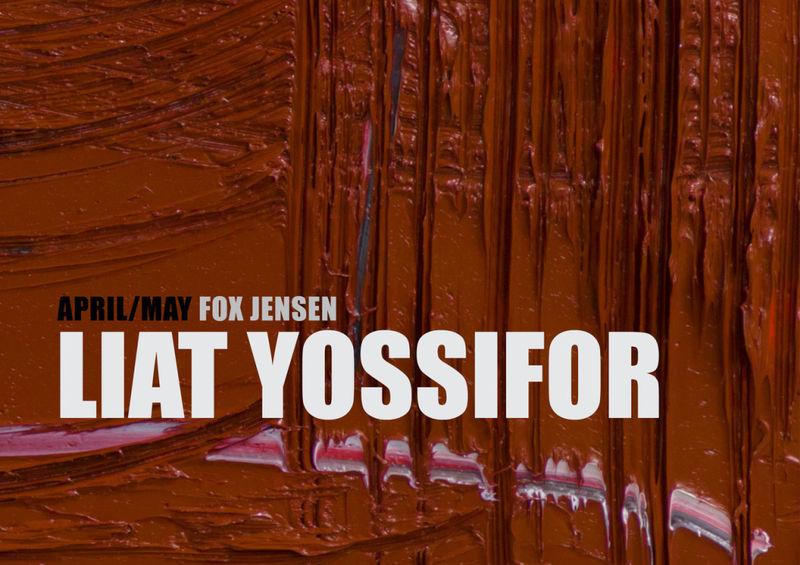

Detail of Wide Red used on the Fox Jensen online gallery invitation, 2020

Detail of Wide Red used on the Fox Jensen online gallery invitation, 2020

With the paintings in limbo but packed to go, I was happily able to spend a leisurely afternoon with them in Yossifor’s studio in Hollywood. Partially encased and propped on cinder blocks, three, square works were leaning side-by-side along the longest wall. What at first glance might appear as the zero degree of painting—echoing Rodchenko’s monochrome triptych—explodes with infinite variation. Far from a statement, a manifesto, a program in the service of ideology, as in the purported purity of Rodchenko’sPure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure BlueColor, Yossifor’s paintings embody experience in all its complexity. Muddying the notions of reduction, essence, and endpoint, her canvases emanate plenitude, generosity, openness, uncontainable possibility and impenetrable mystery. Revisiting the almost exclusively male history of abstraction, Yossifor injects non-objective painting with fresh lifeblood right when its proliferation (dubbed “zombie painting” by some critics) announces an aesthetic demise.

Through my engagement with the paintings and speaking with Yossifor about her practice over the last few years, I have become increasingly drawn to how the recent paintings communicate with other sometimes much earlier works, the majority of which I have only ever seen in reproduction. There are myriad ways the distinct bodies of work interconnect and constitute a dialogue spanning the arc of her career. The process of reminiscence inherent to her practice thus obliquely reveals the fleeting presence of surviving images, like the characters in the post-apocalyptic subplot of Wenders’ filmmise en abyme.

In their materiality, her recent oil on linen works fall clearly within the long tradition of painting. Yet their “objectness” defies medium-specificity. The textured impastoed surfaces with their incised lines evoke drawing or the etched surfaces of printmaking rather than painterly brush strokes. They take on the properties of sculptural reliefs—the paint, like wet clay, becoming less malleable as it thickens and dries. Digging into the painted ground, whose viscosity varies depending on the color, with palette knives, the sharp end of a paintbrush handle, a steel wire brush, spackling spatulas, or novel instruments, the artist seems to be probing the history of the medium, its relation to history, and her own personal history, revealing yet concealing, offering glimpses, glimmers, glints of these interwoven narrative threads.

Wide Black, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, side view

Wide Black, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, side view

Conceived as an installation intended to invite deambulation and contemplation, her 2020 exhibition“No second chances in the land of a thousand dances,”comprises seven paintings meant to converse across the gallery space. With this recent group of works, Yossifor reintroduces deep red to a minimalist palette that has oscillated between the opaquest of blacks, streaked with swirls of white like shooting stars across a vast night sky, and countless gradations of grey, resulting from tangles of blue, yellow and red folded into the monochrome white ground.

Wide Grey, oil on linen, 81 x 78 inches, installation view

Wide Grey, oil on linen, 81 x 78 inches, installation view

Across swaths of soft grey, broad smooth swirls serpentine through sharper finer lines betraying hints of black, blue, or flesh tone accents inWide Grey. Eschewing the color-blending function of the palette, the artist uses the painting’s surface as a depository to empty several dozen large tubes of oil paint for the ground, into which the other hues are folded and mixed together through thealla primaor wet-on-wet gestural process. This intimate dance binds figure and ground while streaking, staining, tainting and sullying any notion of a true monochrome. Yossifor likens the grey paintings, variations on which she has been painting since 2011, to bodies. Curving, swooping marks swirl and spin like a whirling dervish or the twirling motions of a dancer performing the interiorized movements of an oft-repeated choreography.

Wide Red, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, 2020, installation view

Wide Red, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, 2020, installation view

Earthy red, which the artist associates with skins and blood, joins the grey and black abstractions for the first time in the current show. InWide Red, a swarthy layer of scratched and scarred vermillion paint signals a return to Yossifor’s earliest body of work, a series executed nearly two decades ago from 2002 to 2006, when she was exploring her heritage (see below). Moving away from a kind of figuration that too readily prompted a reductive reading, the Israeli-born artist began to explore other pictorial modes which would allow her to literally dig further into the paint in order to probe deeply embedded meaning.

These earlier works are incised into oil paint on board. Twenty-seven half-length, bust or head shots of uniformed young women depict conscripted Israeli soldiers in hues ranging from white and pink to red and black. Crosshatched lines etched into monochromatic fields of color demarcate the spectral figures, which emerge like apparitions from a vertically striated ground, activated by the shifting effects of light. Details of these figurative works display an uncanny resemblance to her new abstractions; the mark-making uniting them bears witness to the continuity of their core concern—embodiment.

InWide Black, white commingles with red, blue and brown lines, which are largely absorbed into the dense black paint, unlike the grey canvases, which become attenuated in the process. The artist relates the black works both to the void and to writing. The additive and subtractive procedures integral to Yossifor’s process evokethe layering of a palimpsest, in which the accrual of marks over several days also involves effacement and reinscription, with one line partially erasing another and gradually embedding the figures deeper into the ground.

Wide Black, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, 2020, installation view

Wide Black, oil on linen, 80 x 78 inches, 2020, installation view

The precision and control of the meticulously rendered soldiers—her peers—and the freer, more spontaneous, “automatic” drawing of the most recent exuberantly gestural abstractions are self-referential, elusively inscribing the body of the artist. Her gestures but also her physical shape become the measure of the work, a template for the dimensions of the canvas—the female figure recasting the idealized proportions of Leonardo’sVitruvian Man.The tall or wide expanses of gesture, color, and texture trace her movements, which comprise the improvisational yet repeated performance animating the paintings. This pas-de-deux between the artist and the painting also resonates with or (re)activates other bodies and enlivens the shadowy figures lurking in the depths.

The artist explains how she drew inspiration from hermusée imaginaireto inform the current body of work displayed at Fox Jensen. The four figurative paintings she references—by Max Beckmann, Marsden Hartley, Jean Fautrier and Giorgio de Chirico[i]—do indeed deploy a similar color scheme; but more significantly, they point to a range of obscured concerns haunting her abstractions, and held in tension in works such asDusk(2006) andTear Drop(2007), which feature the interplay of figuration and abstraction.

Against moody, dramatic skies, deformed or amorphous black mounds of scored paint merge into the monstrous foreboding landscape. Conjuring a mass of maimed, mutilated, dying and dead bodies, the central motif is an allegorical battleground on which the metaphysical and the visceral face off. The pictorial plane constitutes the stage where the artist grapples with the multifarious dimensions of perception, identity and perspective. Alluding to similar questions linking nationality, nation, and nationalism to incipient violence,Double Headed(2010) (below), offers yet another, although distinctive, bridge between the earliest and most recent bodies of work.

Collapsing figure and ground, the abstractions fuse psychic and physical energy in an alchemical union of opposing principles. Yet they complicate these binary structures. Beyond the reconciliation of opposites—light and dark, interior and exterior, black and white, back and forth, give and take—the intertwining figures oscillate across time and space in an oeuvre that is at once painterly, graphic, sculptural, abstract yet figural or spectral like cast shadows. The traces of a body that is always in flux exude a powerful magnetic force; the pictorial surfaces vibrate, shimmer and come alive with the incremental shifts in their immediate environment, impelling the viewer to move forward or to the side from another angle, multiplying perspectives, stepping back and circling round again in an attempt to capture their fleeting mystery.

The mesmerizing physicality of Yossifor’s paintings is intrinsically bound up in their elegant raw materiality as much as their interplay with their surroundings and their existence as objects in space. They cast their spell, breathe almost like living beings. Exuberant yet nearly silent, there exists still a constant buzz or whisper, the pounding pulse of a heartbeat or a faint breath grazing skin. They grasp and envelop the viewer, enthralled, in their gaze. This is lyrical, poetic painting that alters our sense of time and space, transporting us and surreptitiously transforming our perception.

If any question remains as to the efficacy of translating into virtual terms the multisensorial and largely haptic operation Yossifor’s paintings command, then perhaps some clues lie in the screen-saturated distancing of the present moment. Though the images on a screen, whether moving or still, handheld or wall-mounted, undoubtedly have the potential to move us, to induce emotion, the disembodied referent falls short of grabbing us viscerally the way the actual paintings do. The bodily experience of the artwork in space, on the walls of the studio or in the gallery, is restrained to a flick of a finger, clicking the keyboard, swiping across or scrolling down the smooth surface of the screen. The slowness of sauntering and lingering transfixed in the presence of the paintings is reduced to a split-second zooming in and out. This schism, which has been exponentially augmented by the current conundrum—whereby presence and touch portend bodily threat, offering us little choice but to embrace distance and virtual encounter—quite productively illuminates and heightens our awareness of the mechanisms at work in two vastly different modes of perceiving, and by extension, of what is lost or gained in translation.

Like the eponymous1982 filmby Wim Wenders, which revolves around a science fiction film cast and crew stranded together on location when the production is stalled due to sudden lack of funds, Liat Yossifor’s latest body of work was on its way to Sydney, Australia for a solo show at Fox Jensen Gallery scheduled to open on March 28 when it became stranded in shipping crates, postponed in the voyage to its destination, and ultimately consigned to a screen, thus suffering a fate similar to that of nearly all exhibitions slated for this Spring at galleries and museums around the globe.

While greatly diminishing the work’s impact, paradoxically, the online viewing room of Fox Jensen offers potentially greater visibility for the work. Does it do so at the expense of its living vitality and vibrant energy?

With the paintings in limbo but packed to go, I was happily able to spend a leisurely afternoon with them in Yossifor’s studio in Hollywood. Partially encased and propped on cinder blocks, three, square works were leaning side-by-side along the longest wall. What at first glance might appear as the zero degree of painting—echoing Rodchenko’s monochrome triptych—explodes with infinite variation. Far from a statement, a manifesto, a program in the service of ideology, as in the purported purity of Rodchenko’sPure Red Color, Pure Yellow Color, Pure BlueColor, Yossifor’s paintings embody experience in all its complexity. Muddying the notions of reduction, essence, and endpoint, her canvases emanate plenitude, generosity, openness, uncontainable possibility and impenetrable mystery. Revisiting the almost exclusively male history of abstraction, Yossifor injects non-objective painting with fresh lifeblood right when its proliferation (dubbed “zombie painting” by some critics) announces an aesthetic demise.

Through my engagement with the paintings and speaking with Yossifor about her practice over the last few years, I have become increasingly drawn to how the recent paintings communicate with other sometimes much earlier works, the majority of which I have only ever seen in reproduction. There are myriad ways the distinct bodies of work interconnect and constitute a dialogue spanning the arc of her career. The process of reminiscence inherent to her practice thus obliquely reveals the fleeting presence of surviving images, like the characters in the post-apocalyptic subplot of Wenders’ filmmise en abyme.

In their materiality, her recent oil on linen works fall clearly within the long tradition of painting. Yet their “objectness” defies medium-specificity. The textured impastoed surfaces with their incised lines evoke drawing or the etched surfaces of printmaking rather than painterly brush strokes. They take on the properties of sculptural reliefs—the paint, like wet clay, becoming less malleable as it thickens and dries. Digging into the painted ground, whose viscosity varies depending on the color, with palette knives, the sharp end of a paintbrush handle, a steel wire brush, spackling spatulas, or novel instruments, the artist seems to be probing the history of the medium, its relation to history, and her own personal history, revealing yet concealing, offering glimpses, glimmers, glints of these interwoven narrative threads.

Conceived as an installation intended to invite deambulation and contemplation, her 2020 exhibition“No second chances in the land of a thousand dances,”comprises seven paintings meant to converse across the gallery space. With this recent group of works, Yossifor reintroduces deep red to a minimalist palette that has oscillated between the opaquest of blacks, streaked with swirls of white like shooting stars across a vast night sky, and countless gradations of grey, resulting from tangles of blue, yellow and red folded into the monochrome white ground.

Across swaths of soft grey, broad smooth swirls serpentine through sharper finer lines betraying hints of black, blue, or flesh tone accents inWide Grey. Eschewing the color-blending function of the palette, the artist uses the painting’s surface as a depository to empty several dozen large tubes of oil paint for the ground, into which the other hues are folded and mixed together through thealla primaor wet-on-wet gestural process. This intimate dance binds figure and ground while streaking, staining, tainting and sullying any notion of a true monochrome. Yossifor likens the grey paintings, variations on which she has been painting since 2011, to bodies. Curving, swooping marks swirl and spin like a whirling dervish or the twirling motions of a dancer performing the interiorized movements of an oft-repeated choreography.

Earthy red, which the artist associates with skins and blood, joins the grey and black abstractions for the first time in the current show. InWide Red, a swarthy layer of scratched and scarred vermillion paint signals a return to Yossifor’s earliest body of work, a series executed nearly two decades ago from 2002 to 2006, when she was exploring her heritage (see below). Moving away from a kind of figuration that too readily prompted a reductive reading, the Israeli-born artist began to explore other pictorial modes which would allow her to literally dig further into the paint in order to probe deeply embedded meaning.

These earlier works are incised into oil paint on board. Twenty-seven half-length, bust or head shots of uniformed young women depict conscripted Israeli soldiers in hues ranging from white and pink to red and black. Crosshatched lines etched into monochromatic fields of color demarcate the spectral figures, which emerge like apparitions from a vertically striated ground, activated by the shifting effects of light. Details of these figurative works display an uncanny resemblance to her new abstractions; the mark-making uniting them bears witness to the continuity of their core concern—embodiment.

InWide Black, white commingles with red, blue and brown lines, which are largely absorbed into the dense black paint, unlike the grey canvases, which become attenuated in the process. The artist relates the black works both to the void and to writing. The additive and subtractive procedures integral to Yossifor’s process evokethe layering of a palimpsest, in which the accrual of marks over several days also involves effacement and reinscription, with one line partially erasing another and gradually embedding the figures deeper into the ground.

The precision and control of the meticulously rendered soldiers—her peers—and the freer, more spontaneous, “automatic” drawing of the most recent exuberantly gestural abstractions are self-referential, elusively inscribing the body of the artist. Her gestures but also her physical shape become the measure of the work, a template for the dimensions of the canvas—the female figure recasting the idealized proportions of Leonardo’sVitruvian Man.The tall or wide expanses of gesture, color, and texture trace her movements, which comprise the improvisational yet repeated performance animating the paintings. This pas-de-deux between the artist and the painting also resonates with or (re)activates other bodies and enlivens the shadowy figures lurking in the depths.

The artist explains how she drew inspiration from hermusée imaginaireto inform the current body of work displayed at Fox Jensen. The four figurative paintings she references—by Max Beckmann, Marsden Hartley, Jean Fautrier and Giorgio de Chirico[i]—do indeed deploy a similar color scheme; but more significantly, they point to a range of obscured concerns haunting her abstractions, and held in tension in works such asDusk(2006) andTear Drop(2007), which feature the interplay of figuration and abstraction.

Against moody, dramatic skies, deformed or amorphous black mounds of scored paint merge into the monstrous foreboding landscape. Conjuring a mass of maimed, mutilated, dying and dead bodies, the central motif is an allegorical battleground on which the metaphysical and the visceral face off. The pictorial plane constitutes the stage where the artist grapples with the multifarious dimensions of perception, identity and perspective. Alluding to similar questions linking nationality, nation, and nationalism to incipient violence,Double Headed(2010) (below), offers yet another, although distinctive, bridge between the earliest and most recent bodies of work.

Collapsing figure and ground, the abstractions fuse psychic and physical energy in an alchemical union of opposing principles. Yet they complicate these binary structures. Beyond the reconciliation of opposites—light and dark, interior and exterior, black and white, back and forth, give and take—the intertwining figures oscillate across time and space in an oeuvre that is at once painterly, graphic, sculptural, abstract yet figural or spectral like cast shadows. The traces of a body that is always in flux exude a powerful magnetic force; the pictorial surfaces vibrate, shimmer and come alive with the incremental shifts in their immediate environment, impelling the viewer to move forward or to the side from another angle, multiplying perspectives, stepping back and circling round again in an attempt to capture their fleeting mystery.

The mesmerizing physicality of Yossifor’s paintings is intrinsically bound up in their elegant raw materiality as much as their interplay with their surroundings and their existence as objects in space. They cast their spell, breathe almost like living beings. Exuberant yet nearly silent, there exists still a constant buzz or whisper, the pounding pulse of a heartbeat or a faint breath grazing skin. They grasp and envelop the viewer, enthralled, in their gaze. This is lyrical, poetic painting that alters our sense of time and space, transporting us and surreptitiously transforming our perception.

If any question remains as to the efficacy of translating into virtual terms the multisensorial and largely haptic operation Yossifor’s paintings command, then perhaps some clues lie in the screen-saturated distancing of the present moment. Though the images on a screen, whether moving or still, handheld or wall-mounted, undoubtedly have the potential to move us, to induce emotion, the disembodied referent falls short of grabbing us viscerally the way the actual paintings do. The bodily experience of the artwork in space, on the walls of the studio or in the gallery, is restrained to a flick of a finger, clicking the keyboard, swiping across or scrolling down the smooth surface of the screen. The slowness of sauntering and lingering transfixed in the presence of the paintings is reduced to a split-second zooming in and out. This schism, which has been exponentially augmented by the current conundrum—whereby presence and touch portend bodily threat, offering us little choice but to embrace distance and virtual encounter—quite productively illuminates and heightens our awareness of the mechanisms at work in two vastly different modes of perceiving, and by extension, of what is lost or gained in translation.