Jennie C. Jones and the Music of Chance

Hyperallergic / Mar 1, 2022 / by Seph Rodney / Go to Original

Installation view, Jennie C. Jones: Dynamics, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum (photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2022)

At the Guggenheim museum there is a small gallery, the first space open to visitors who begin at the ground floor, to climb the slow upward spiral. It is a unique space because if one continues on the upward trajectory, one eventually arrives at a large window in which all the works in the lower gallery become visible from a distinctly different angle. If you are visiting Jennie C. Jones’s Dynamics exhibition, you should look at the work in that gallery from both vantages. At the higher point, the subtle fissures, ridges, and folds of color that Jennie C. Jones embeds in her paintings become more apparent. There are shy and subtle, a vivacious child hidden in the folds of her mother’s dress and peeking out now and again to see whether you are paying attention.

Installation view of a gallery from above at Jennie C. Jones: Dynamics, the Solomon R. Guggenheim museum

My noticing these furtive aspects of Jennie C. Jones’s work is strongly inflected by my experience as a teenager seeing Barnett Newman’s paintings at the Museum of Modern Art. I remember being transfixed by the rigorous demarcation of space, one field of color separated from another by a resolute line cleanly and affirmatively lain down, a rebuke to the chaos I experienced growing up in a home with two adults who did not like each other and whose animus bled everywhere it could bleed. I was drawn to Newman’s ability to construct order out of all the disorder that is all around me, tilling one plot of land until the rows were perfectly straight all the way to the horizon. And in a few paintings, for example “Onement I” (1948), there would be a line that had a little wobble to it, was uneven, showed a bit of the underpainting, wavering a little on its path. Seeing these pieces felt like someone who knew more than I did admitting to me that there would always be a little unsettledness in the world, that even my own innate instability would roil my consciousness and make me feel unmoored from time to time. But I love the forceful assertion of control. In discussing his own paintings, he said in the pages of Artnews in 1966: “I wanted to hold the emotion, not waste it in picturesque ecstasies. The cry, the unanswerable cry is world without end. But a painting has to hold it, world without end, in its limits.” But what if instead, where you are from the sound you hear is a plea to be let out?

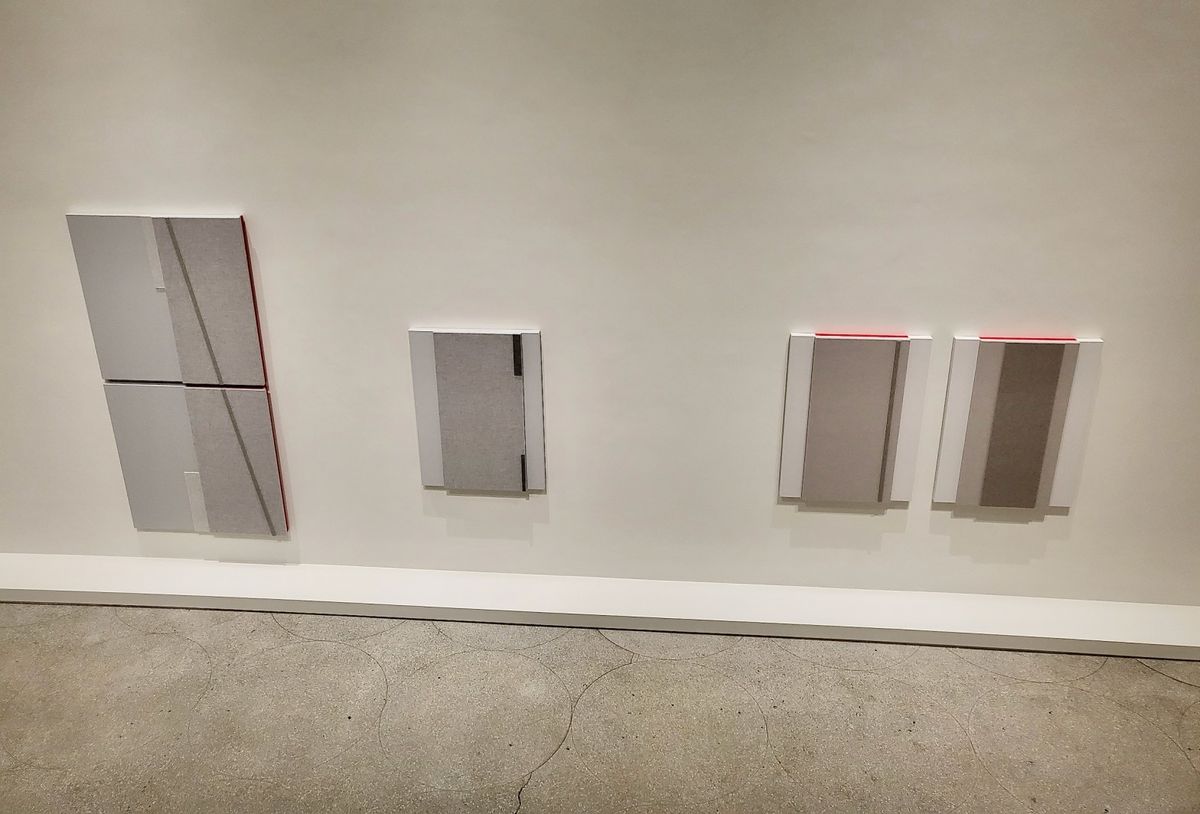

This is how I come to Jones’s work, seeing the Dynamics pieces from above and realizing that her resolute line is a line of incursion, of inquisitiveness. Her colorful contours are all about surprise. They show up among the felt and acoustic panels that are mostly variations of gray in seams of red or lively lime green. They appear at the tops of the works or at the edges that touch the supporting wall. This means that as a viewer, if I only face the work I’ll miss a lot of it. I need to scout around it, get up on tiptoes or climb a ladder to the glimpse the tops, nose up to the wall to see where the sly color is hidden.

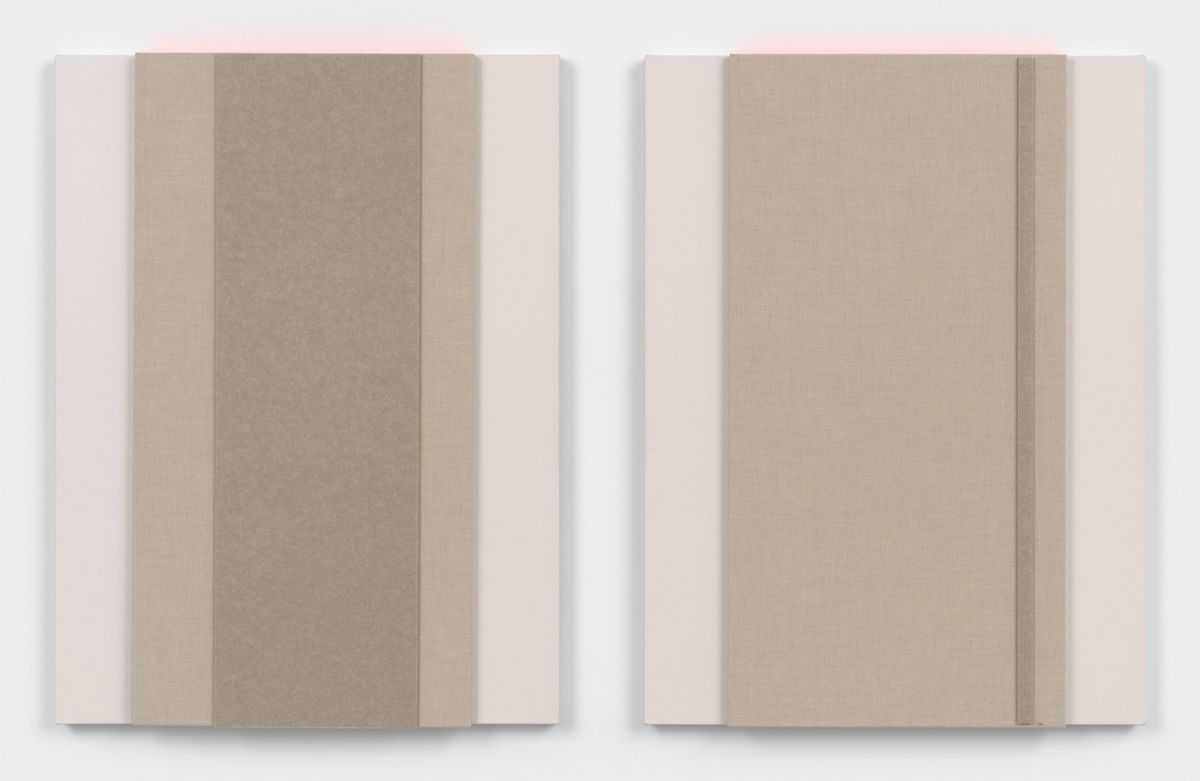

This is to say that Jones is playful and coy where Newman was white knuckling it. While Newman sweats it out, Jones is exacting but still mischievous. In the piece, “Neutral [Clef] Structure 1st & 2nd,” (all works 2021), which consists of a side-by-side diptych of equally sized acoustic panels in varying tones of gray, though they seem to measure the same, everything on them is a little anomalous. None of the shapes are centered, and though all the painted shapes are variations of the rectangle, they don’t quite align. The middle quadrant isn’t quite in the middle, the right edge not the same width as the left edge. It’s a playful asymmetry that doesn’t seek so much to assert a certain kind of order, or declare what order should look like, as it is simply engaged in ongoing negotiations around balance and presence. And then there’s the peekaboo effect of the small glow of red pigment along the top ridge of both pieces. In the work “To the Pedal Point,” which looks like one off-white painting almost on top of its twin, but with the bottom sibling angled against the floor as if acting as a wedge to keep her sister in the air, there is a seam of red between them and on top, and below, at the foot, there is some sort of red-painted foundation, with a corresponding red bracket on or against the lower painting. There is whimsy here and a little restraint.

Jennie C. Jones, “Neutral [clef] Structure 1st & 2nd" (2021) acoustic panel and acrylic on canvas, diptych, 121.9 × 91.4 × 8.9 cm each (© Jennie C. Jones, courtesy Alexander Gray Associates, New York, and Patron Gallery, Chicago)

Valerie Cassel Oliver discloses in her catalogue essay “Liner Notes for a Compilation” that in an email exchange with the curator, Jones admits that she is “afraid of color.” Of course. We fear the untamed streak in ourselves, the sensory, wild child who snatches the ribbon of pigment from its hiding place, grabbing the tapered edge and running with it coloring everything in her path until there is no tape left. Jones uses these very measured panels and clean surfaces to hold that trepidation in check and the tension between these two urgencies operates dialectically: The child tugs the adult by the hand, wanting to take them toward some adventure, while the adult checks her enthusiasm, slows her progress, urges caution, and their arms become tightropes between them.

Jennie C. Jones, “To the Pedal Point" (2021) (photo: David Heald © Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation, 2022)

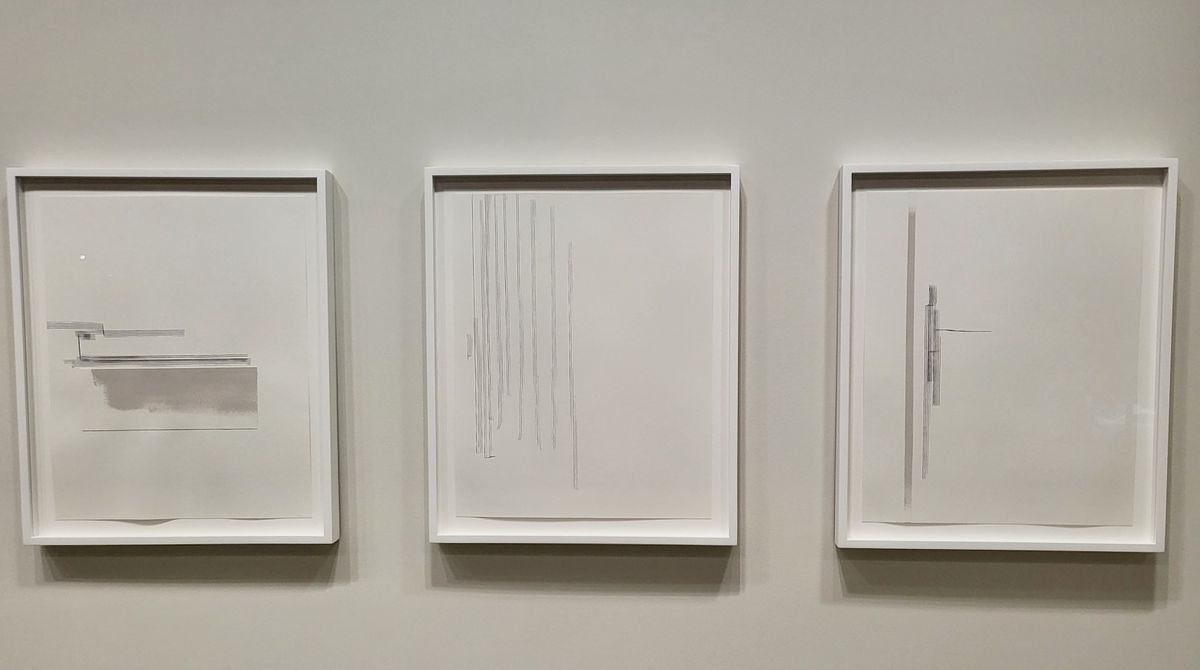

And there is delicateness in this show as well, particularly in the paper pieces that at first glance might be holding musical notation. In works such as “A Score for Tenderness and Grace,” it takes a moment to notice that the orientation of the staves that are typically horizontal in music manuscript paper is vertical here and the lines are too close together. There are graphite lines that mass along one border and then a broad, washy stroke of ink nearby, and then a line heading off into the distance with its own hidden agenda. Much has been written and theorized about the profound relationship between music, particularly avant-garde music, and Jones’s paintings and drawings, but here is where that relationship seems most palpable to me. These are quiet pieces, but they suggest an atonal drumming, a skittering sound in this distance that I can’t quite pick up, but I imagine others can access. What Jones says in her conversation with Huey Copeland published in the 2015 exhibition catalogue Compilation is:

A solid white painting of a black painting or something that’s got a sound panel on it also hopefully has an elegance and a quietness to it that can have some emotional effect that can make you and be connected to a kind of mindful listening.

Jennie C. Jones, “A Score for Tenderness and Grace" (2021) set of ten ink, acrylic, and paper collages, mounted on paper (image by the author)

In some ways listening is a state of mind, or a mood, as much as it is an act of intention.

With approximately 22 pieces (plus a sound installation), ultimately the show felt like the right size. It expanded and deepened my understanding of Jones’s work, but ultimately the work feels a little too self-contained for me when it is not shown in dialogue with other artists. When that parley happens, her work feels like an assertion of aesthetic personality, rather than a mediation of it. I have seen the artist’s work in group shows over the years: at the Generations show in Baltimore two years ago, and the 2018, multi-site, Chicago exhibition Out of Easy Reach. In each of these previous encounters, the work always felt like it kept its own counsel no matter what work was next to it. There is always at least one child on the playground who has developed some interior psychic gyroscope that keeps her firmly oriented on whatever game she is playing with whatever objects are at hand — despite the roiling, boisterous actions of others around her. It’s because these works exude a kind of still self-determination that I find myself listening attentively, but I can only sustain that attention for so long and the work only takes me so far.

I wondered whether my feeling of being intrigued, but not completely beguiled might be shared, so I looked at her exhibition record. Though I hadn’t previously experienced a solo exhibition of Jones’s work, she has had several major shows at various prominent institutions in the past decade or so, including her first mid-career retrospective at Contemporary Arts Museum Houston in 2015, a show that covered approximately 12 years of work. Other major survey and solo exhibitions include a show in New York at the Kitchen in 2011, at the Hirschhorn Museum in Washington DC in 2013, the Glass House historic site in Connecticut in 2018, and at the Arts Club of Chicago in 2020. It seems that there is a robust and enduring interest in her restrained version of abstraction that precisely balances itself across three fence posts: a conceptual support of music, a minimalist style, and bits of colorful exuberance.

In what feels like the right coda to this experience, when I climb to the top of the museum I see there are several cupolas with chairs and small tables conducive to creating a small listening group of two or three people. I sit and wait for the music that’s supposed to arrive. It does. “Oculus Tone” is a sound installation that lasts three minutes and it delightfully mirrors the visual work in that there is a low, rich, rolling tone which makes me think of the experimental music of Ryuichi Sakamoto or Jean Michele Jarre, though this is less complicated and rhythmic. But about the last third of the piece, a high chord shows up, surfing on top of the other sounds. It is keening, searching for color, pleading to be let out, and for a short time it is.

Jennie C. Jones: Dynamics continues at the Guggenheim Museum (1071 Fifth Ave, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through May 2. It was curated by by Lauren Hinkson.