Carmen Winant’s lessons in looking

Artforum / Mar 11, 2022 / by Cassie Packard / Go to Original

INSTRUCTIONAL PHOTOGRAPHY: LEARNING HOW TO LIVE NOW, BY CARMEN WINANT. London: SPBH Editions, 2021. 119 pages.

“LET ME PAUSE HERE to say that ‘instructional photographs’ is a term that I have made up; there is no preexisting dedicated category for this kind of picture,” writes artist Carmen Winant in her slim, pocketable book Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now. On the opposite page, a woman gingerly pulls hardened plaster from her face; culled from a photographic “how-to” on mask-making, the black-and-white image has been shorn of captions and context, extricated from the words and sequencing that make it legible to viewers as an instruction rather than an image. The second publication in SPBH’s series of artist-authored books on contemporary photography, following Duncan Wooldridge’s To Be Determined: Photography and the Future, Winant’s photo-essay is a love letter to a familiar photographic vernacular so critically neglected—didacticism is, after all, deeply unfashionable—that it necessitated a neologism.

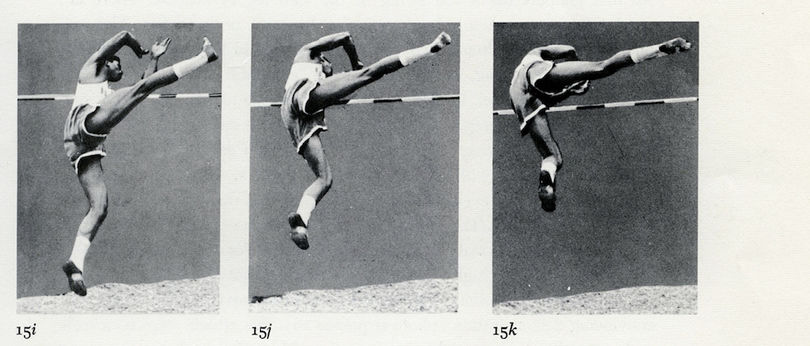

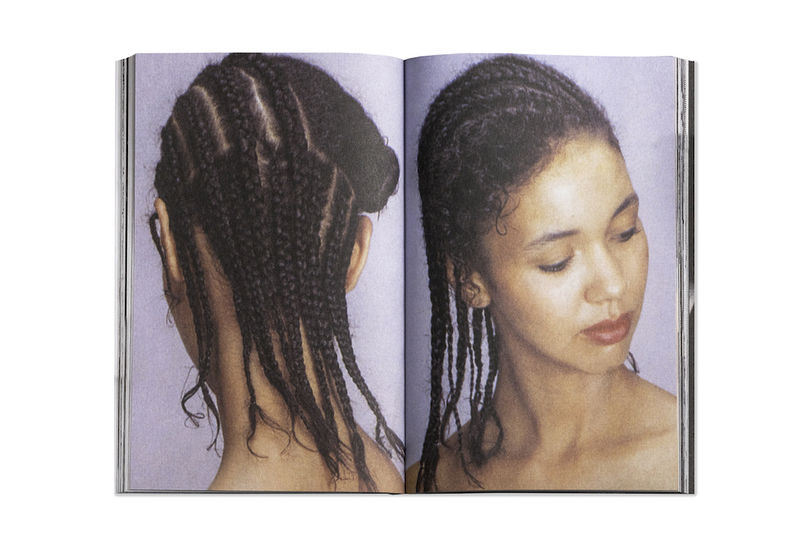

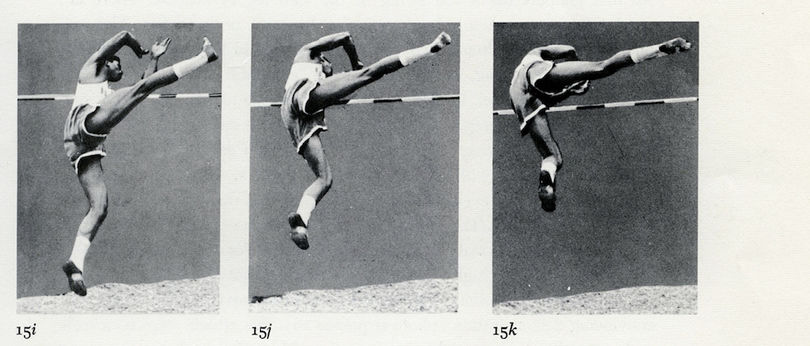

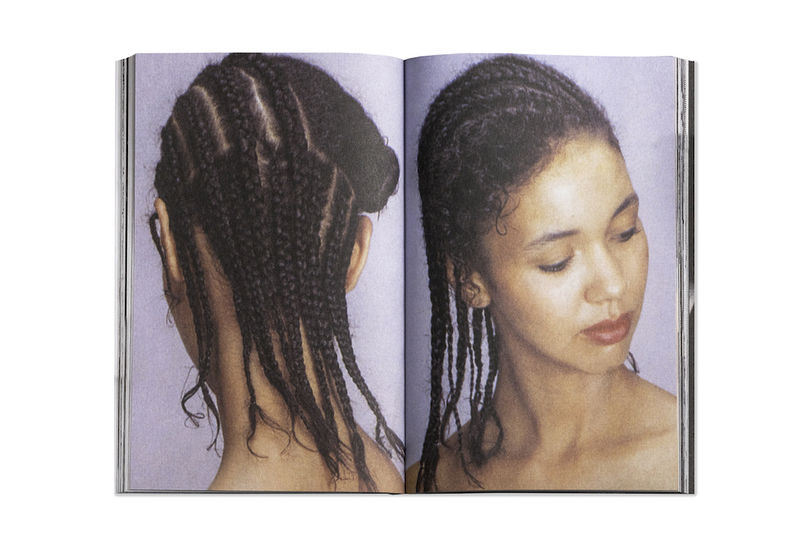

Parceled into small blocks of text with as little as a single sentence consigned to a page, Winant’s ruminations on instructional photography are unexpectedly moving. The artist characterizes these photos as “guides, particularly in moments of personal and collective awakening,” noting that she turned to such imagery to learn, to cite one example, Lamaze breathing. Running parallel to the text are scores of photographs, appropriated from vintage books and pamphlets, each designed to teach spectators “how to”: braid hair, train a dog, meditate, bandage a finger, masturbate, high jump.

Winant, who selected the images from thousands of examples in her studio, has amassed found photographs under thematic or iconographic umbrellas before. In 2018, between the birth of her first and second child, the artist papered a hall at New York’s Museum of Modern Art with two-thousand images of childbirth. Her Warburg-adjacent found photo installations have since addressed similarly embodied subjects of pleasure and touch, exploring their simultaneously solitary and collective character.

The appropriated photos in Instructional Photography are variously eaten by the book gutter, closely cropped to the brink of abstraction, obscured by conspicuous cut-and-paste jobs, irrationally sequenced, or presented as isolated images: subtle strategies of defamiliarization that thwart the genre’s punctilious commitment to clarity and chronology. “Instructional photographs have something to teach me about arrangement, flow, density—and ultimately—seeing,” Winant writes. Here, fragmentation and repetition make the world knowable: A grisaille figure skater’s turn unfolds across four gridded images and a ribbed ceramic pot takes shape across six. (An exhibition of Winant’s work at Patron Gallery in Chicago last year included mobiles made from the pages of how-to crafting books, a major vehicle of instructional photography.)

The decentralized, serial nature of this frequently authorless and antiheroic category of images certainly owes something to the work of Eadweard Muybridge, who in 1878 pioneered motion photography to understand equine gaits (with the help of leading Black jockeys such as G. Domm, who expertly calibrated the horses’ pacing) and, in ensuing years, documented myriad other forms of animal and human locomotion across hundreds of photographic series. Decades later, motion photography didn’t just capture movement; it began to choreograph it, too, when scientific management engineers Frank and Lillian Gilbreth made photographic studies of factory workers’ movements to determine how they might be streamlined for maximum efficiency (supposedly on behalf of not only profit but also worker wellbeing). Beyond its effects on motion in the factory, on the athletic field, or in the kitchen, Muybridge’s modular vision also exerted an intergenerational influence on artists. Among them were Marcel Duchamp and the systems- and seriality-oriented Conceptualists who followed him, such as Mel Bochner, who cited Muybridge’s significance in a December 1967 Artforum article titled “The Serial Attitude,” and Sol LeWitt, who made work in direct homage to Muybridge—including sculptural boxes with photographs in peepholes—throughout the 1960s, the same decade in which he embarked upon his series of wall drawings comprising verbal and graphic instructions.

Winant’s borrowed instructional photographs echo the Gilbreths’ interest in productivity without their capitalist underpinnings, the Conceptualists’ anticommodity thrust without their cool intellectualism; her selection tends to instead emphasize DIY principles of autonomy and self-direction (occasionally obliquely, as with a tightly cropped image of a chest post-mastectomy, drawn from a book on breast appreciation). Whether they depict someone building a box or executing a Pap smear, the assembled photographs prompt the viewer to map another body’s somatic knowledge onto their own. Does any other photographic category elicit such an active, even empathic, form of viewership? “It is all there, laid out for me on the page across dozens of photographs and staged by a body double,” writes Winant of ridding clay of bubbles and conducting breast self-exams. With the broad (infinitely, cheaply replicable) distribution of a panoply of phantom bodily knowledge, self-reliance becomes a communal practice.

Winant’s images center women protagonists. A variety of ethnic backgrounds are depicted, though a dearth of elderly, visibly disabled, and trans women raises questions about whose blind spots we might be seeing. Winant’s archival sources are largely left ambiguous, although her text mentions How to Stay Out of the Gynecologist’s Office (1981), a photo-heavy medical self-help publication released by the Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers, as well as Joani Blank’s I Am My Lover (1978), a book about female masturbation with accompanying photographs by Honey Lee Cottrell—found, Winant recalls, in a secondhand shop near JEB’s photobook Making a Way: Lesbians Out Front (1987). Cottrell and JEB participated in the Ovulars, photographic workshops held in the early 1980s on womyn’s land in Oregon, one of the self-sustaining communities founded by and for women (predominantly White, cisgender lesbians) that sprang up in rural pockets throughout the US in the 1960s and ’70s. The Ovulars, whose image production appeared in Winant’s 2019 photo-essay “Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression through the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us,” fostered skill-sharing and community-building as they helped women picture themselves, even spawning a short-lived photography magazine with “how-to” articles such as “Using Color Negative Film” and “Living Feminist Photography.”

The advent of womyn’s lands at the nexus of feminist/lesbian separatism, a countercultural ideology that encouraged women to sever ties with men, and the back-to-the-land movement, which spurred middle-class urbanites to relocate to rural areas in search of self-sufficiency, coincided with broader antiauthoritarian currents of radical self-care, DIY culture, and self-help (a relatively politically coherent forerunner to the present scramble of at-home firearm fabrication software, “how you can help” infographics, inexhaustible YouTube tutorials, and Goop’s questionable gynecological counsel). It isn’t out of the question that the various manifestations of a drive to learn “how to” live outside of a patriarchal, capitalist society in the 1960s and ’70s might have produced something like a golden age of instructional photography. A radical charge buzzes under the surface of the instructional photos here. In an argument largely made through images, Winant demonstrates that they have much to teach us still.

Detail from Carmen Winant’s Instructional Photography (SPBH, 2021).

“LET ME PAUSE HERE to say that ‘instructional photographs’ is a term that I have made up; there is no preexisting dedicated category for this kind of picture,” writes artist Carmen Winant in her slim, pocketable book Instructional Photography: Learning How to Live Now. On the opposite page, a woman gingerly pulls hardened plaster from her face; culled from a photographic “how-to” on mask-making, the black-and-white image has been shorn of captions and context, extricated from the words and sequencing that make it legible to viewers as an instruction rather than an image. The second publication in SPBH’s series of artist-authored books on contemporary photography, following Duncan Wooldridge’s To Be Determined: Photography and the Future, Winant’s photo-essay is a love letter to a familiar photographic vernacular so critically neglected—didacticism is, after all, deeply unfashionable—that it necessitated a neologism.

Parceled into small blocks of text with as little as a single sentence consigned to a page, Winant’s ruminations on instructional photography are unexpectedly moving. The artist characterizes these photos as “guides, particularly in moments of personal and collective awakening,” noting that she turned to such imagery to learn, to cite one example, Lamaze breathing. Running parallel to the text are scores of photographs, appropriated from vintage books and pamphlets, each designed to teach spectators “how to”: braid hair, train a dog, meditate, bandage a finger, masturbate, high jump.

Winant, who selected the images from thousands of examples in her studio, has amassed found photographs under thematic or iconographic umbrellas before. In 2018, between the birth of her first and second child, the artist papered a hall at New York’s Museum of Modern Art with two-thousand images of childbirth. Her Warburg-adjacent found photo installations have since addressed similarly embodied subjects of pleasure and touch, exploring their simultaneously solitary and collective character.

Detail from Carmen Winant’s Instructional Photography (SPBH, 2021).

The appropriated photos in Instructional Photography are variously eaten by the book gutter, closely cropped to the brink of abstraction, obscured by conspicuous cut-and-paste jobs, irrationally sequenced, or presented as isolated images: subtle strategies of defamiliarization that thwart the genre’s punctilious commitment to clarity and chronology. “Instructional photographs have something to teach me about arrangement, flow, density—and ultimately—seeing,” Winant writes. Here, fragmentation and repetition make the world knowable: A grisaille figure skater’s turn unfolds across four gridded images and a ribbed ceramic pot takes shape across six. (An exhibition of Winant’s work at Patron Gallery in Chicago last year included mobiles made from the pages of how-to crafting books, a major vehicle of instructional photography.)

The decentralized, serial nature of this frequently authorless and antiheroic category of images certainly owes something to the work of Eadweard Muybridge, who in 1878 pioneered motion photography to understand equine gaits (with the help of leading Black jockeys such as G. Domm, who expertly calibrated the horses’ pacing) and, in ensuing years, documented myriad other forms of animal and human locomotion across hundreds of photographic series. Decades later, motion photography didn’t just capture movement; it began to choreograph it, too, when scientific management engineers Frank and Lillian Gilbreth made photographic studies of factory workers’ movements to determine how they might be streamlined for maximum efficiency (supposedly on behalf of not only profit but also worker wellbeing). Beyond its effects on motion in the factory, on the athletic field, or in the kitchen, Muybridge’s modular vision also exerted an intergenerational influence on artists. Among them were Marcel Duchamp and the systems- and seriality-oriented Conceptualists who followed him, such as Mel Bochner, who cited Muybridge’s significance in a December 1967 Artforum article titled “The Serial Attitude,” and Sol LeWitt, who made work in direct homage to Muybridge—including sculptural boxes with photographs in peepholes—throughout the 1960s, the same decade in which he embarked upon his series of wall drawings comprising verbal and graphic instructions.

Winant’s borrowed instructional photographs echo the Gilbreths’ interest in productivity without their capitalist underpinnings, the Conceptualists’ anticommodity thrust without their cool intellectualism; her selection tends to instead emphasize DIY principles of autonomy and self-direction (occasionally obliquely, as with a tightly cropped image of a chest post-mastectomy, drawn from a book on breast appreciation). Whether they depict someone building a box or executing a Pap smear, the assembled photographs prompt the viewer to map another body’s somatic knowledge onto their own. Does any other photographic category elicit such an active, even empathic, form of viewership? “It is all there, laid out for me on the page across dozens of photographs and staged by a body double,” writes Winant of ridding clay of bubbles and conducting breast self-exams. With the broad (infinitely, cheaply replicable) distribution of a panoply of phantom bodily knowledge, self-reliance becomes a communal practice.

Spread from Carmen Winant’s Instructional Photography (SPBH, 2021).

Winant’s images center women protagonists. A variety of ethnic backgrounds are depicted, though a dearth of elderly, visibly disabled, and trans women raises questions about whose blind spots we might be seeing. Winant’s archival sources are largely left ambiguous, although her text mentions How to Stay Out of the Gynecologist’s Office (1981), a photo-heavy medical self-help publication released by the Federation of Feminist Women’s Health Centers, as well as Joani Blank’s I Am My Lover (1978), a book about female masturbation with accompanying photographs by Honey Lee Cottrell—found, Winant recalls, in a secondhand shop near JEB’s photobook Making a Way: Lesbians Out Front (1987). Cottrell and JEB participated in the Ovulars, photographic workshops held in the early 1980s on womyn’s land in Oregon, one of the self-sustaining communities founded by and for women (predominantly White, cisgender lesbians) that sprang up in rural pockets throughout the US in the 1960s and ’70s. The Ovulars, whose image production appeared in Winant’s 2019 photo-essay “Notes on Fundamental Joy; seeking the elimination of oppression through the social and political transformation of the patriarchy that otherwise threatens to bury us,” fostered skill-sharing and community-building as they helped women picture themselves, even spawning a short-lived photography magazine with “how-to” articles such as “Using Color Negative Film” and “Living Feminist Photography.”

The advent of womyn’s lands at the nexus of feminist/lesbian separatism, a countercultural ideology that encouraged women to sever ties with men, and the back-to-the-land movement, which spurred middle-class urbanites to relocate to rural areas in search of self-sufficiency, coincided with broader antiauthoritarian currents of radical self-care, DIY culture, and self-help (a relatively politically coherent forerunner to the present scramble of at-home firearm fabrication software, “how you can help” infographics, inexhaustible YouTube tutorials, and Goop’s questionable gynecological counsel). It isn’t out of the question that the various manifestations of a drive to learn “how to” live outside of a patriarchal, capitalist society in the 1960s and ’70s might have produced something like a golden age of instructional photography. A radical charge buzzes under the surface of the instructional photos here. In an argument largely made through images, Winant demonstrates that they have much to teach us still.