Lost, and Now Found, Art From the Civil Rights Era

The New York Times / Mar 10, 2020 / by Hilarie M. Sheets / Go to Original

The famed black art Jacob Lawrence painted a multi-panel series from 1954-56 whose pieces were scattered over time. They have now been reunited.

During the civil rights movement in the mid-1950s, Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) — one of the leading black artists of his day — painted a series of 30 panels re-examining early American history.

The series, “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” presented a radically integrated view of the nation’s founding, including unheralded contributions of African-Americans in the fight to build a new democracy. But at that tumultuous time in race relations, the work was received with some ambivalence by the art world. The collection was eventually purchased by a private collector who later resold each panel separately.

The majority of these little-seen paintings have been reunited for the first time in roughly 60 years in“Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle,”on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., through April 26. (The show will then travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, the Seattle Art Museum and the Phillips Collection in Washington.)

“The series resonates because we’re in a moment where so much important work is being done to recover histories that we were never taught,” saidAusten Barron Bailly, chief curator of Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Ark., who co-curated the exhibition alongside Elizabeth Hutton Turner, a professor at the University of Virginia. The exhibit also features works by three contemporary artists who similarly plumb historical archives to inform their art — creating a dialogue with Mr. Lawrence’s deeply researched, intimately scaled paintings.

“Struggle” is the only narrative cycle by Mr. Lawrence, out of the 10 he painted, not preserved intact in public collections. His“The Migration Series”is a 60-panel work chronicling the mass movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North. It was jointly purchased by the Museum of Modern Art and the Phillips Collection in 1941 and catapulted Mr. Lawrence into the mainstream art world at a time when few black artists were represented.

Mr. Lawrence’s dealer,Charles Alan, exhibited “Struggle” twice at his gallery in the late 1950s and approached many major museums about acquiring it. But he could find no buyer. Ms. Bailly speculated that people couldn’t quite reconcile how Mr. Lawrence, as a black artist who had traditionally worked on more African-American centered subject matter, now no longer segregated “black” history from what many might have considered “American” history. “The politics of integration, of the art world, of post-Brown v. Board of Education, played a role in the reception of this project,” Ms. Bailly said.

Mr. Alan eventually sold the series to a private collector,William Meyers, but without stipulating that the panels couldn’t be resold individually. Mr. Meyers did just that in the 1960s, scattering the series and relegating it to obscurity, until now. The whereabouts of five panels remain unknown. “The people that still have the ones we don’t know about probably don’t even know that they are part of a series,” said Lydia Gordon, coordinating curator of the show at the Peabody Essex. The curators hope the missing paintings will surface with the attention of the national tour.

Throughout “Struggle,” Mr. Lawrence recasts familiar historical events, from the Revolutionary War through the War of 1812, that were formative in the nation’s birth. The 10th panel, for instance, reframes George Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River in December 1776, which was immortalized in themonumental painting by Emanuel Leutzein 1851. In Mr. Leutze’s work, the founding father stands heroically at the helm of one of the row boats traversing the icy river, leading his men to what would be a successful surprise attack against the German Hessian troops in Trenton, N.J.

In Mr. Lawrence’s version, however, there is not a single protagonist. On the choppy blue waters, three crowded boats of men huddle under blankets, with no indication of who might be Washington. The painting is accompanied by the words ofWashington’s aide-de-camp, Tench Tilghman, reflecting on the communal bravery demonstrated that day: “The night was excessively severe … which the men bore without the least murmur.”

Each panel includes text with such eyewitness accounts of history, which Mr. Lawrence compiled from 1949 to 1954 at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). There he discovered documentation of black men freely enlisting to fight alongside Washington in the Revolutionary War.

The artist himself had served during World War II on the first racially integrated boat in the U.S. Coast Guard, which he later described as “the best democracy I’ve ever known.”

Throughout the series, Mr. Lawrence painted his figures using sienna and umber skin tones, deliberately obscuring racial differences with these earthen hues. “It’s confusing, you don’t know who’s white and who’s black,” Ms. Gordon said. “It’s this really poetic rumination on the collective struggle.”

The exhibition brings “Struggle” into the 21st century by juxtaposing it with the work of living artists also questioning and revising entrenched narratives of history.Hank Willis Thomas, 43, was in high school when he first came across Mr. Lawrence’s “Migration Series” in 1992 at the Phillips Collection. “It shaped my notion of storytelling ever since,” said Mr. Thomas, who, like Mr. Lawrence, frequently uses source material drawn from the archives of the Schomburg Center where his mother,Deborah Willis, was the curator throughout his childhood.

In the show, Mr. Thomas’s sculpture “Rich Black Specimen #460” (2017) is based on a tiny metal stock image of a runaway slave from 1859 that was once used in printed advertisements. He blew up this dehumanizing silhouette to a larger than life-size figure. Cast in aluminum with black powder coating, the sculpture is tinged at the edges with the printing colors of cyan, magenta and yellow as though this representation of a person is beginning to come into full color.

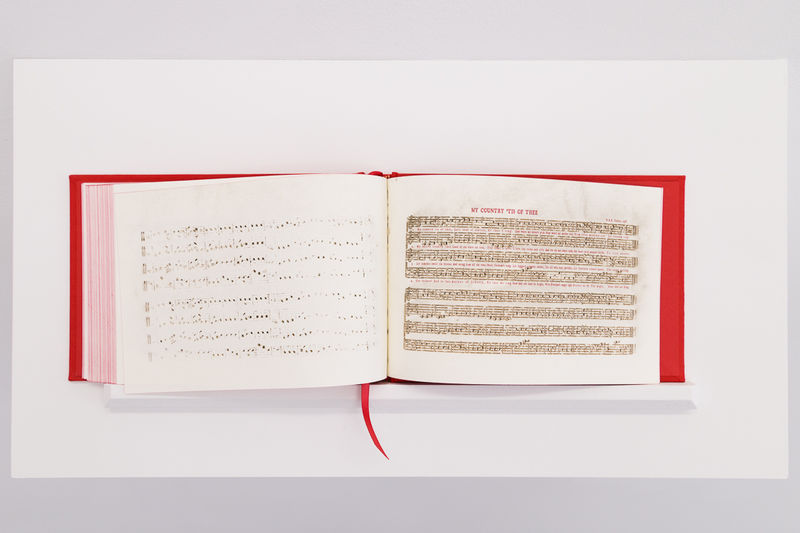

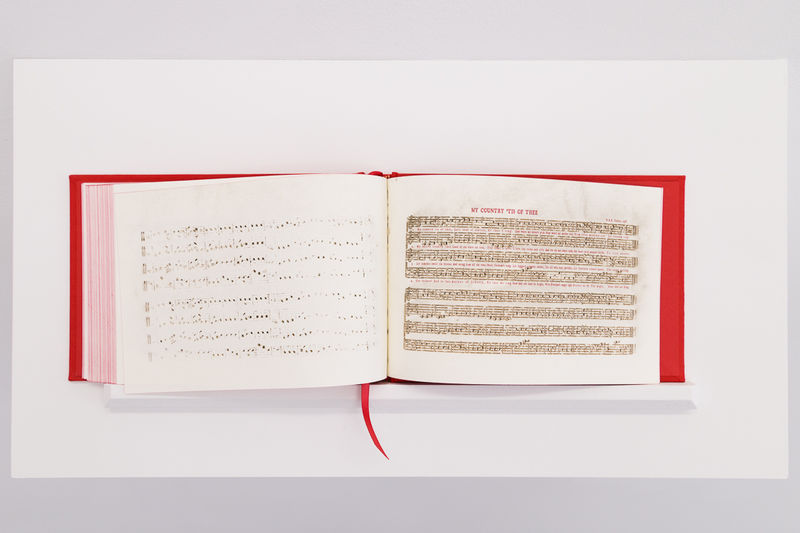

“America: A Hymnal” by Bethany Collins featuresa book printed with the lyrics of 100 different versions of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” Bethany Collins; Photo: Tim Johnson, via PEM

Another gallery adjacent to “Struggle” is a chapel-like space featuringBethany Collins’s “America: A Hymnal” (2017), a book printed with the lyrics of 100 different versions of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” written between the 18th and 20th centuries, variously supporting revolution, abolition, temperance, suffrage, the confederacy and slavery.

“They’re contradictory and dissenting versions of what it means to be American,” said Ms. Collins, 36, who has burned away the musical notes in the hymnal, leaving just the words legible. A soundscape reverberates through the gallery with six vocalists singing the different lyrics simultaneously to the culturally ingrained tune, at once familiar and estranging.

Ms. Collins wasn’t aware of Mr. Lawrence’s “Struggle” series until approached by the curators, but felt an immediate connection when she saw it. She said that Mr. Lawrence’s “idea that you don’t understand the entirety of what it means to be American unless you have multiple perspectives telling the story feels relevant in this moment and related to my practice.”

Derrick Adams, 50, draws a straight line between his personal path to Mr. Lawrence, whom he first discovered as a young artist in Baltimore while writing a book report at the public library. Strongly identifying with the renown artist, Mr. Adams was motivated in 1993 to transfer to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn where Mr. Lawrence had once taught. There, Mr. Adams had the honor of chaperoning his hero, who had returned to the school to accept an award. The serendipitous encounter “was a confirmation, for me, that I was on the right track,” said Mr. Adams.

In a homage to Mr. Lawrence, Mr. Adams created an installation titled “Jacob’s Ladder” for the exhibition. In it, Mr. Lawrence’s studio chair sits on a wallpaper collage of 100 reproductions of photos from his personal albums, archived in Seattle. These images run along the floor, up the wall and paper a ladder, which leads to a portrait by Mr. Adams of his spiritual mentor.

“It’s incredible to have this really personal touchstone with Lawrence’s DNA,” Ms. Gordon said. “Derrick’s interpretation from the biblical story of the angels moving up and down the ladder speaks to Lawrence’s ability to constantly inspire him as well as future generations.”

During the civil rights movement in the mid-1950s, Jacob Lawrence (1917-2000) — one of the leading black artists of his day — painted a series of 30 panels re-examining early American history.

The series, “Struggle: From the History of the American People,” presented a radically integrated view of the nation’s founding, including unheralded contributions of African-Americans in the fight to build a new democracy. But at that tumultuous time in race relations, the work was received with some ambivalence by the art world. The collection was eventually purchased by a private collector who later resold each panel separately.

The majority of these little-seen paintings have been reunited for the first time in roughly 60 years in“Jacob Lawrence: The American Struggle,”on view at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Mass., through April 26. (The show will then travel to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Birmingham Museum of Art in Alabama, the Seattle Art Museum and the Phillips Collection in Washington.)

“The series resonates because we’re in a moment where so much important work is being done to recover histories that we were never taught,” saidAusten Barron Bailly, chief curator of Crystal Bridges in Bentonville, Ark., who co-curated the exhibition alongside Elizabeth Hutton Turner, a professor at the University of Virginia. The exhibit also features works by three contemporary artists who similarly plumb historical archives to inform their art — creating a dialogue with Mr. Lawrence’s deeply researched, intimately scaled paintings.

“Struggle” is the only narrative cycle by Mr. Lawrence, out of the 10 he painted, not preserved intact in public collections. His“The Migration Series”is a 60-panel work chronicling the mass movement of African-Americans from the Jim Crow South to the North. It was jointly purchased by the Museum of Modern Art and the Phillips Collection in 1941 and catapulted Mr. Lawrence into the mainstream art world at a time when few black artists were represented.

Mr. Lawrence’s dealer,Charles Alan, exhibited “Struggle” twice at his gallery in the late 1950s and approached many major museums about acquiring it. But he could find no buyer. Ms. Bailly speculated that people couldn’t quite reconcile how Mr. Lawrence, as a black artist who had traditionally worked on more African-American centered subject matter, now no longer segregated “black” history from what many might have considered “American” history. “The politics of integration, of the art world, of post-Brown v. Board of Education, played a role in the reception of this project,” Ms. Bailly said.

Mr. Alan eventually sold the series to a private collector,William Meyers, but without stipulating that the panels couldn’t be resold individually. Mr. Meyers did just that in the 1960s, scattering the series and relegating it to obscurity, until now. The whereabouts of five panels remain unknown. “The people that still have the ones we don’t know about probably don’t even know that they are part of a series,” said Lydia Gordon, coordinating curator of the show at the Peabody Essex. The curators hope the missing paintings will surface with the attention of the national tour.

Throughout “Struggle,” Mr. Lawrence recasts familiar historical events, from the Revolutionary War through the War of 1812, that were formative in the nation’s birth. The 10th panel, for instance, reframes George Washington’s famous crossing of the Delaware River in December 1776, which was immortalized in themonumental painting by Emanuel Leutzein 1851. In Mr. Leutze’s work, the founding father stands heroically at the helm of one of the row boats traversing the icy river, leading his men to what would be a successful surprise attack against the German Hessian troops in Trenton, N.J.

In Mr. Lawrence’s version, however, there is not a single protagonist. On the choppy blue waters, three crowded boats of men huddle under blankets, with no indication of who might be Washington. The painting is accompanied by the words ofWashington’s aide-de-camp, Tench Tilghman, reflecting on the communal bravery demonstrated that day: “The night was excessively severe … which the men bore without the least murmur.”

Each panel includes text with such eyewitness accounts of history, which Mr. Lawrence compiled from 1949 to 1954 at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library (now the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). There he discovered documentation of black men freely enlisting to fight alongside Washington in the Revolutionary War.

The artist himself had served during World War II on the first racially integrated boat in the U.S. Coast Guard, which he later described as “the best democracy I’ve ever known.”

Throughout the series, Mr. Lawrence painted his figures using sienna and umber skin tones, deliberately obscuring racial differences with these earthen hues. “It’s confusing, you don’t know who’s white and who’s black,” Ms. Gordon said. “It’s this really poetic rumination on the collective struggle.”

The exhibition brings “Struggle” into the 21st century by juxtaposing it with the work of living artists also questioning and revising entrenched narratives of history.Hank Willis Thomas, 43, was in high school when he first came across Mr. Lawrence’s “Migration Series” in 1992 at the Phillips Collection. “It shaped my notion of storytelling ever since,” said Mr. Thomas, who, like Mr. Lawrence, frequently uses source material drawn from the archives of the Schomburg Center where his mother,Deborah Willis, was the curator throughout his childhood.

In the show, Mr. Thomas’s sculpture “Rich Black Specimen #460” (2017) is based on a tiny metal stock image of a runaway slave from 1859 that was once used in printed advertisements. He blew up this dehumanizing silhouette to a larger than life-size figure. Cast in aluminum with black powder coating, the sculpture is tinged at the edges with the printing colors of cyan, magenta and yellow as though this representation of a person is beginning to come into full color.

“America: A Hymnal” by Bethany Collins featuresa book printed with the lyrics of 100 different versions of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee.” Bethany Collins; Photo: Tim Johnson, via PEM

Another gallery adjacent to “Struggle” is a chapel-like space featuringBethany Collins’s “America: A Hymnal” (2017), a book printed with the lyrics of 100 different versions of “My Country, ’Tis of Thee” written between the 18th and 20th centuries, variously supporting revolution, abolition, temperance, suffrage, the confederacy and slavery.

“They’re contradictory and dissenting versions of what it means to be American,” said Ms. Collins, 36, who has burned away the musical notes in the hymnal, leaving just the words legible. A soundscape reverberates through the gallery with six vocalists singing the different lyrics simultaneously to the culturally ingrained tune, at once familiar and estranging.

Ms. Collins wasn’t aware of Mr. Lawrence’s “Struggle” series until approached by the curators, but felt an immediate connection when she saw it. She said that Mr. Lawrence’s “idea that you don’t understand the entirety of what it means to be American unless you have multiple perspectives telling the story feels relevant in this moment and related to my practice.”

Derrick Adams, 50, draws a straight line between his personal path to Mr. Lawrence, whom he first discovered as a young artist in Baltimore while writing a book report at the public library. Strongly identifying with the renown artist, Mr. Adams was motivated in 1993 to transfer to Pratt Institute in Brooklyn where Mr. Lawrence had once taught. There, Mr. Adams had the honor of chaperoning his hero, who had returned to the school to accept an award. The serendipitous encounter “was a confirmation, for me, that I was on the right track,” said Mr. Adams.

In a homage to Mr. Lawrence, Mr. Adams created an installation titled “Jacob’s Ladder” for the exhibition. In it, Mr. Lawrence’s studio chair sits on a wallpaper collage of 100 reproductions of photos from his personal albums, archived in Seattle. These images run along the floor, up the wall and paper a ladder, which leads to a portrait by Mr. Adams of his spiritual mentor.

“It’s incredible to have this really personal touchstone with Lawrence’s DNA,” Ms. Gordon said. “Derrick’s interpretation from the biblical story of the angels moving up and down the ladder speaks to Lawrence’s ability to constantly inspire him as well as future generations.”